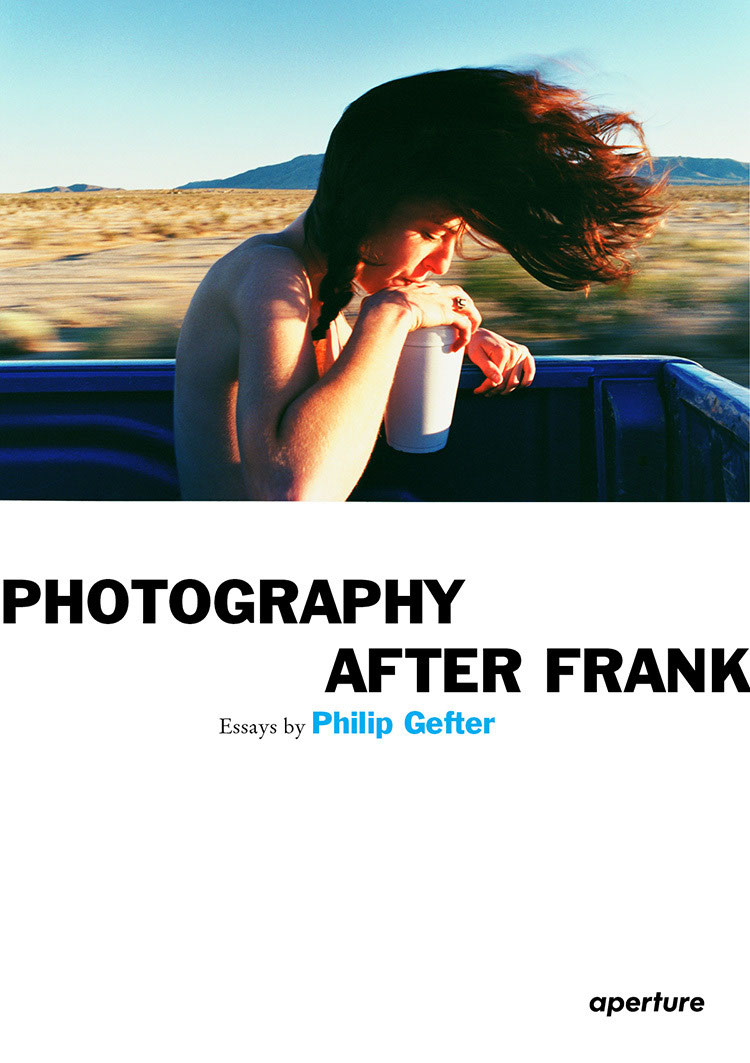

PHOTOGRAPHY

AFTER FRANK

Essays by Philip Gefter

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

THE DOCUMENT

Why MoMA Is Giving Its Largest Solo Photography Exhibition Ever to Lee Friedlander

Travels with Walker, Robert, and Andy

On Stephen Shore

Southern Exposures: Past and Present Through the Lens of William Christenberry

John Szarkowski, Curator of Photography, Dies at Eighty-one

The Imagists Eye

On Henry Wessel

Beauty Is Not a Four-letter Word

On Richard Misrach

The Tableau Inside Your Town Hall

On Paul Shambroom

Bernd Becher, Seventy-five, Photographer of German Industrial Landscape, Dies

Keeping It Real: Photo-Realism

Portraits of American Paradises, Mostly Lost

On Joel Sternfeld

Keeping His Eye on the Horizon (Line)

On Sze Tsung Leong

THE STAGED DOCUMENT

Photographic Icons: Fact, Fiction, or Metaphor?

The Picnic That Never Was

On Beate Gtschow

As Unpretty as a Picture

On Eric Fischl

Moments in Time, Yet Somehow in Motion

On JoAnn Verburg

Robert Polidori: In the

A Young Man With an Eye, and Friends Up a Tree

On Ryan McGinley

PLATES

PHOTOJOURNALISM

Page One: A Conversation with Philip Gefter, Picture Editor of the New York Times Front Page

By Vronique Vienne

Historys First Draft Looks Much Better With Pictures

Reflections of New Yorks Luckiest: Look Magazine

Reading Newspaper Pictures: A Thousand Words, and Then Some

Cornell Capa, Photojournalist and Museum Founder, Dies at Ninety

THE PORTRAIT

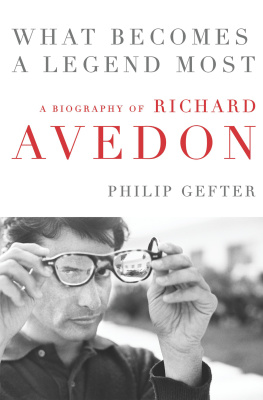

Defining Beauty Through Avedon

Self-portrait as Obscure Object of Desire

On Jack Pierson

Is That Portrait Staring at Me?

On Fiona Tan

A Pantheon of Arts and Letters in Light and Shadow

On Irving Penn

A Photographers Lie

On Annie Leibovitz

Embalming the American Dreamer

On Katy Grannan

THE COLLECTION

What Eighty-five Hundred Pictures Are Worth

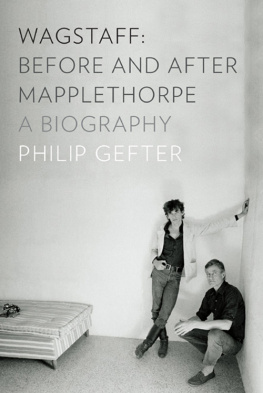

The Man Who Made Mapplethorpe: A Film About Sam Wagstaff

The Avedon Eye, Trained on Faces Captured By Others

Photography Reveals Itself Between Covers

Culture in Context: Photographs in Vince Alettis Magazine Collection

For Photography, Extreme Home Makeover

THE MARKETPLACE

The Theater of the Street, the Subject of the Photograph

On Philip-Lorca diCorcia

Why Photography Has Supersized Itself

A Thousand Words? How About $450,000?

From a Studio in Arkansas, a Portrait of America

On Mike Disfarmer

Whats New in Photography: Anything but Photos

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

REPRODUCTION CREDITS

Plate

Frank Paulin, Playland Cadillac, Times Square, New York 1956

This image dates from the same period as the photographs in Robert Franks The capturing the tenor of the moment when black-and-white street photography began to define the medium. Paulins perfect symmetry leads the eye directly to the center of the frame, to the word announcing the medium that renders in complex optical description a time, a place, and an era.

INTRODUCTION

In the broad sweep of art history, photography is just a blip, coming at the tail end of a long continuum that reflects and parallels the evolution of consciousness. From cave drawings to Greek sculpture to Italian frescoes to French neo-Classical painting, art-making over time is a story about increasingly refined tools, measured accuracy in representing the objective world, and eventually, a gradual progression into perceptual abstraction. Accordingly, the history of art can be viewed as a sequential narrative that charts over thousands of years the simultaneous stages of necessity, invention, and imagination to reveal, ultimately, the manifest intelligence of the species in the complexity of human expression.

Still, during photographys own brief history, humankind has never been brought into sharper focus. Overall, photography has given us a self-adjusting clarity about who we are, what we look like, and how we behave, reflecting our worldindividually, culturally, scientifically, and, ultimately, existentiallyin ways unimaginable merely two hundred years ago. Whether the camera is a scientific, utilitarian, or artistic tool has ceased to be the relevant debate.

Daguerre, Nipce, and Talbot brought civilization to a new stage of consciousness with the invention of photography around 1839. Life, for the first time, could be captured in its truest visual facsimile. Photographys evolutionalong with its progression to cinema, television, video, and, ultimately, cyberspacehas given us the ability to review almost every aspect of our lives instantaneously, if we want, and with exacting detail.

These tools of observation have allowed us a stunning overview of the world in which we livein fact, nothing less than images of the planet Earth itself, just to put things in perspective, as well as the prenatal development of a human being from conception. But the same technology has brought us to a paradoxical self-consciousness: while the photographic image provides heightened awareness about what is real and factual, the constant representation of who we are in visual terms brings with it a meta-consciousness that refracts authentic, or spontaneous, experience.

One irony of photographys invention is that, while it emerged concurrently with a shift toward Realism in painting, it was artists themselves who grew indignant at the idea that a mechanical method of representation could be elevated to the stature of art-making. In 1862, Ingres was among the important artists who issued a bitter denunciation of photography, signing an official petition to the Court in Paris against industrial techniques being applied to art. Perhaps the shorthand ease of perceptual accuracy with which the camera captured the world was too threatening; toward the late nineteenth century painting itself veered toward perceptual abstraction. In the twentieth century art became, then, less about rendering the world with true-to-life objectivity than about the emotional, perceptual, and experiential nature of existence (with recent digressions into deconstructive cultural analysis).

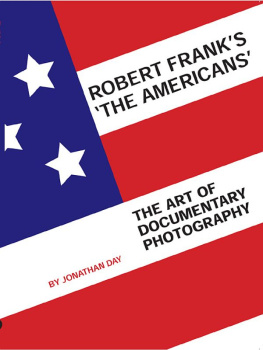

While documentation of the objective world was an underlying principle of art-making in photography for a good part of the twentieth century, the formalism that characterized such factual documentation changed in the 1950s with Robert Frank. His book The published in the U.S. in 1959 (and in France the year before), has come to represent a turning point in photography: his pictures show us common people in ordinary situations, but his documentation was as much about his personal experience as it was about his subject matter. As a result, he changed the look of the photograph and the content of photographic imagery.

The artistic climate in which Frank produced the photographs in The Americans was defined by Abstract Expressionism. Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning rendered spontaneous expression out of the anarchy of form, perhaps setting a precedent for the Beat Generation artists and writers, whose improvisational art-making practices aimed for authenticity and spontaneity in their work as well. Franks pictures reflect the stream-of-consciousness art-making of the period, and his attempt to capture the experience of an authentic moment in visual terms established a departure from the traditional photographic imagery that preceded him. The immediacy, spontaneity, and compositional anarchy in his picture frame changed expectations about the photograph. It created a new way of seeing for subsequent generations of photographers. In fact, The Americans might be looked at today as the apotheosis of the snapshot (the snapshot in and of itself being the backbone of unselfconscious photographic imagery in the twentieth century) and the birth of the snapshot aesthetic.