Also by Philip Gefter

Photography After Frank

Copyright 2015 by Philip Gefter

All rights reserved

First Edition

Youre the Top (from Anything Goes), words and music

by Cole Porter, 1934 (renewed) by WB Music Corp. All rights reserved.

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book,

write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation, a division of

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110

For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact

W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830

Book design by Barbara Bachman

Production manager: Julia Druskin

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

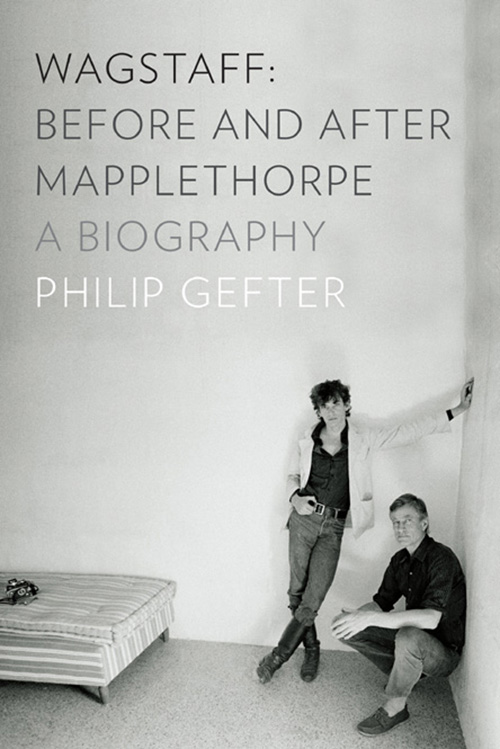

Gefter, Philip.

Wagstaff, before and after Mapplethorpe :

a biography / Philip Gefter. First Edition.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-87140-437-4 (hardcover)

1. Wagstaff, Samuel J. 2. Wagstaff, Samuel J.Friends and associates.

3. Art museum curatorsUnited StatesBiography. 4. ArtCollectors

and collectingUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

N406.W34G44 2014

709.2dc23

[B]

2014029920

ISBN 978-1-63149-015-6 (e-book)

Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

The list of individuals to whom I am indebted, and equally grateful, for their observations about Sam Wagstaff is long; for their memories, expertise, or scholarship; for their encouragement, support, or assistance. At the top, however, is James Crump, who generously brought to my doorstep his own comprehensive research materials for Black, White + Gray, his documentary about WagstaffI relied consistently on this invaluable trove throughout my own research.

Without an editor, a writer is left to become his own worst enemy. Robert Weil, my editor at Liveright, provided focused insight and the kind of rigorous dialogue on the page that every author welcomes. Trent Duffy, an exacting surgeon of the manuscript, not only smoothed grammatical wrinkles and trimmed narrative fat but also held me to the facts with finesse.

Several other editors provided early and meaningful guidance along the way, and I am grateful to each one of them: Samuel Douglas, for his elegance and tone; Maria Russo, who nudged me to trust my intuition; and Craig Seligman, who encouraged me from the beginning.

I appreciate the efforts of Ira Silverberg, the most literary of agents, who first brought the project to Bob Weil, and to Jim Rutman, who continues my representation with a steady hand.

I thank Susan Kismaric, my good friend, for our ongoing, lifelong conversation about photography, as well as for her expertise, keen discernment, and practical assistance. I welcomed the lunches with my good friend Bill Goldstein became a ritual of commiseration about the labor of writing, researching, and making order out of so muchand so littleinformation.

At the J. Paul Getty Museum, Judy Keller not only made possible my museum scholar residency but also generously shared her knowledge and provided access to the museums collection of photographs. I also am grateful for the help of her curatorial staff: Virginia Heckert, Paul Martineau, and Amanda Maddox. At the Getty Research Institute, Marcia Reed, Fran Terpak, and Alexa Sekyra provided kind support; Raquel Zamora, worthy research; and Michelle Brunnick, collegial assistance.

At the Detroit Institute of Arts, Nancy Barr generously shared her notable scholarship and made introductions to people who had known Wagstaff there; at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Gene Gaddis unearthed valuable material from the museums archives.

At the Mapplethorpe Foundation, Joree Adilman and Michael Stout provided unfettered access to their holdings.

To the people I had the pleasure of interviewing about Sam, a genuineif collectivethank you, in particular for the numerous conversations, personal materials, and recollections: Pierre Apraxine, Ellen Brooks, Lynn Davis, Anne Ehrenkranz, Susanne Hilberry, Gerald Incandela, Barbara Jakobson, Judith Jefferson (Sams niece), Peter and Tom Jefferson (Sams nephews), Judy Linn, Anne MacDonald, Maria Morris Hambourg, Weston Naef, Ellen Phelan, George Rinhart, Carol Squiers, John Waddell, Paul Walter, Daniel Wolf, and Clark Worswick.

Several individuals were helpful in idiosyncratic ways and I owe them my gratitude: Vince Aletti, Chris Bollen, Malcolm Daniel, James Danziger, Allen Ellenzweig, Monica Espinel, Megan Feingold, Peter Galassi, Perrin Lathrop, Dimitri Levas, Peter MacGill, Edward Mapplethorpe, Will Menaker, Jeff Rosenheim, John Solomon, and Colin Westerbeck.

Finally, I wish to express my delight to the others from whom I draw inspiration, and not only on the weekend: Franklin Tartaglione, Dave King, Richard Friedman, Robert Hughes, Carey Lebowitz, Simon Lince, Robert Flynt, Jeff MacMahon, Patterson Scarlett, Taylor Mac, Bill Jacobson, Josh Gosfield, Camille Sweeney, Peter Franck, Kathleen Triem, and, across the country and over the years, Kelly Sultan. And, of course, Richard Press, my husband, my inspiration, the perpetual song in my heart.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PHILIP GEFTER was on staff at The New York Times for over fifteen years, where he wrote regularly about photography. His book of essays, Photography After Frank (Aperture), was published in 2009. He also produced the documentary film Bill Cunningham New York (2010). He lives in New York City.

R OBERT MAPPLETHORPE DIED OF AIDS AT THE AGE OF forty-two in 1989. He was the primary heir to Sam Wagstaffs estate, and the Christies catalog of the Mapplethorpe estate sale of October 31, 1989, included several works with the provenance of Wagstaff: James Ensors Stilleben (1896, est. $600,000800,000); Eduoard Vuillards Vue plongeante sur un jardin (Jardin des Nabi) (c. 1900, est. $200,000300,000); John Chamberlains Ultima Thule (undated, est. $100,000200,000); Tony Smiths Throne (undated, est. $100,000150,000); and Andy Warhols Race Riot (1964, four panels, synthetic polymer silk-screened on canvas; est. $700,0001,000,000).

These works of art constitute a partial representation of the legacy of Sam Wagstaff; equally, his acquisition and relish of Jackson Pollocks The Deep, and its later carefully orchestrated sale to the Centre Pompidou in Paris, where it resides today, exemplifies Sams art historical judgment, personal taste, and curatorial stewardship. Other works that he acquired directly from the artists he knew in the 1960s, whether paintings or drawings, today remain bequests of Sam Wagstaff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Detroit Institute of Arts, or the Wadsworth Atheneum in Hartford. His crowning achievementthe Samuel J. Wagstaff Jr. collection of photographs at the J. Paul Getty Museumis considered a cornerstone of that museums photography holdings.

Wagstaff was a thoroughbred in societal terms, a product of class, breeding, and wealth. The arc of his life is drawn on his search for meaningful counterpoints to his privileged, if stultifying, upbringing, those stepping-stones, if you will, into a parallel existence where something approximating enlightenment became his goal. Perhaps his cultivation, in concert with his homosexuality, led him to a less obvious frequency of being, from which he grew to trust his senses, his intuition, and the actuality of his experience. At the same time, he continued to rely on the accumulated knowledge from his fine education to discern what is pureand what was often overlookedin civilization, which he would collect in turn, as if to establish new foundations of thinking about culture and other ways of perceiving the world. Black, White, and Gray, the first museum exhibition of minimalist art, in 1964, was one of his stepping-stones into a portal of expanded consciousness. Sam would follow the artists frequency to a prescient recognition of minimal art, pop art, fluxus, and earth art, with forays into West Somali Dogon sculpture and Native-American Mimbres pots, before turning to photography.

Next page