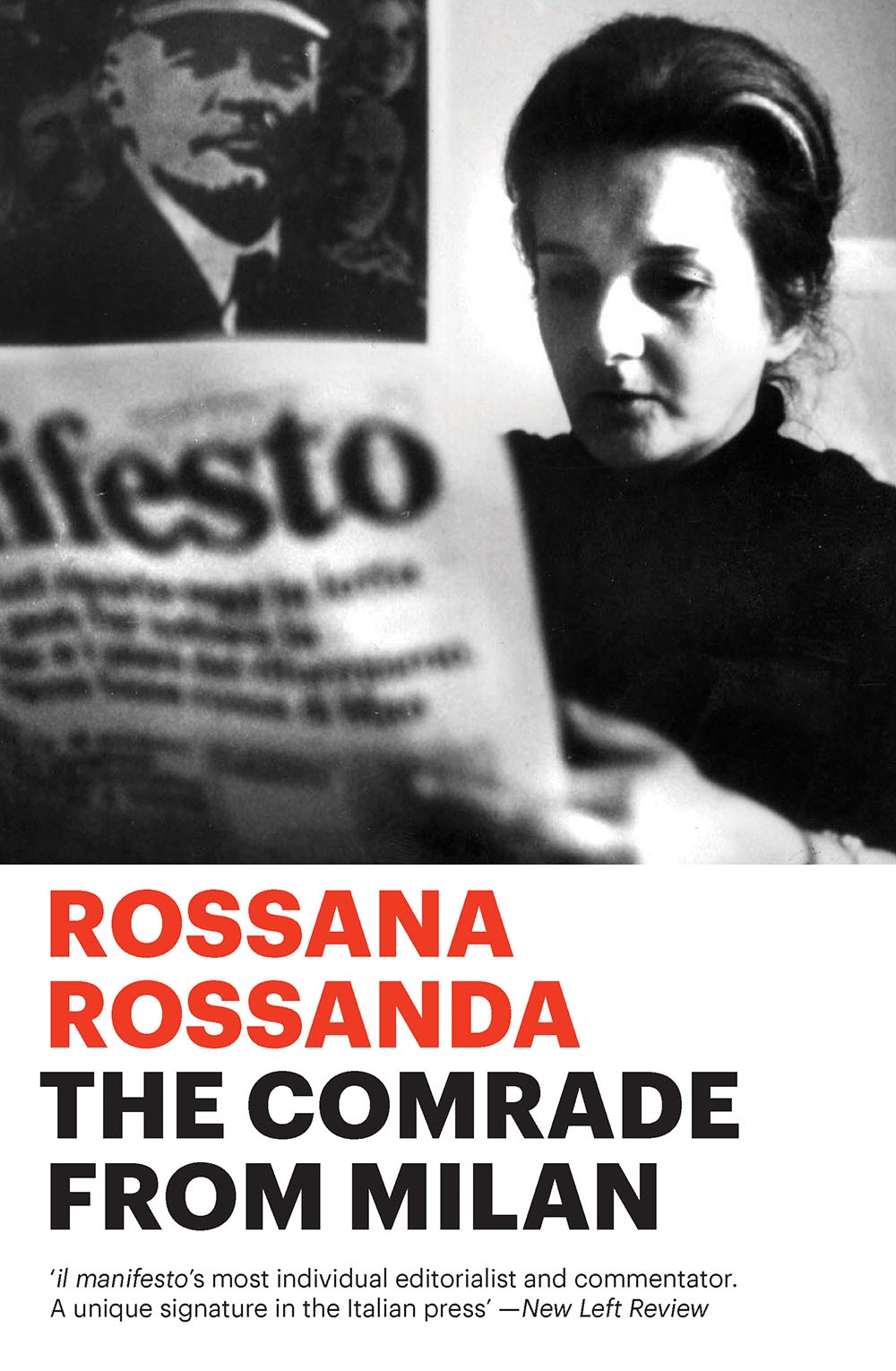

Rossana Rossanda - The Comrade from Milan

Here you can read online Rossana Rossanda - The Comrade from Milan full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: Verso Books, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Comrade from Milan

- Author:

- Publisher:Verso Books

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Comrade from Milan: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Comrade from Milan" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Comrade from Milan — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Comrade from Milan" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

ROSSANA ROSSANDA

Translated by

Romy Clark Giuliani

Verso wishes to express thanks to the Barry Amiel and Norman Melburn

Trust for its generous financial support towards this project

This paperback edition published by Verso 2020

First published in English by Verso 2010

Verso 2010, 2020

Translation Romy Clark Giuliani 2010, 2020

First published as La ragazza del secolo scorso

Giulio Einaudi editore s.p.a., Turin 2005, 2007

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-963-4

ISBN-13: 978-1-78960-152-7 (US EBK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

To the Bear

This is not a history book. It deals with things that surface from my memory when I catch peoples quizzical looks and their expressions interrogate me: Why were you a communist? Why do you say that you are a communist? What do you mean, when you have no party, no position, when you have lost the newspaper that you helped found? Is it an illusion that you cling to, because you are stubborn or stuck in the past? Every so often someone will stop me and say with great kindness: You were a legend! But who wants to be a legend? Legends are the projections of other people and have nothing to do with me. The idea embarrasses me. I am not a name on a memorial plaque to be honoured, who has departed from the world and exists outside of time. I am still struggling with the world and with time. But the question of what it means to be or to have been a communist nags away at me.

The story of communism and twentieth-century communists ended so badly that it is impossible for me not to wonder what it meant to be a communist in Italy in 1943. And by communist, I mean a member of a party, not just someone who holds communist beliefs as a private matter of conscience, which one can always wriggle out of by saying: I had nothing to do with that! To come up with an adequate answer, I begin by questioning myself. Without consulting books or documents, and not without some misgivings.

After half a century of running through the past, stumbling, starting to run again with a few extra bruises, my memory is arthritic. I havent looked after it. I know the pleasures reminiscence brings and its pitfalls, among which is the need to give a shape to the past that it never had. But memory and the shape it takes is one fact among others. Nothing more and nothing less.

These pages would never have been published without the patience of Doriana Ricci and Tiziana Antonelli, who experienced, recorded and put up with the meanderings of my memory.

I have such ambivalent feelings towards these pages that they would have remained on the computer if Saverio Cesari had not looked them over with such affection. This is in part because the wonderful Adriana Cavareros book Tu che mi guardi, tu che mi racconti (You Who Observe Me, You Who Tell My Story) troubled me for such a long time. She is a great thinker, and her book examines the legitimacy of writing about yourself. But is anyone else a less wretched witness to the truth about you? But who will be a less wretched witness to what little you can know of yourself, if the Other without whom we could not live can see you only through his or her equally unreliable lens?

My gratitude goes to these friends and to Severino.

I didnt discover communism at home, thats for sure; or politics either. But then I remember hardly anything of my early childhood, and little of the first seven years in which according to Maria Svetaeva everything is settled. I feel no nostalgia for a happier time, no resentments over tears shed in the middle of the night. Mine must have been a fairly ordinary childhood; a loving one, a sort of antechamber, a chrysalis that I was in a hurry to emerge from and fly away like a butterfly. Except for babies, everyone was like a butterfly to me.

I was born in the 1920s in Pola, confusing various registry offices: Was it Pola, Italy, Pola, Yugoslavia, or Pola now Pula Croatia? At that time it was part of Italy, on the tip of the Istrian peninsula, between green countryside and white rocks hollowed out by the date mussels. Just across from Pola were the islands of Carnaro and other little fragments of islands, like the Fenera and the Scoglio Cielo, which belonged to my mother. I dont know what they are called now; Ive never been back. They were inhabited by wild rabbits. To get to the islands we used a traditional Adriatic two-masted fishing boat. The heavily scented narcissi were as tall as I was, and my mother taught me how to gather the wild asparagus, digging my fingers down into the moss. In some photos, men with guns and women with long waists and caps pushed down over their eyes are staring at me; Im laughing and look silly. I still remember the black snake that slid over the tablecloth spread out on the grass with the boiled eggs and salami, and how everyone jumped up and I felt abandoned. The creature quickly slithered away. Then I remember a red sunset and how on our way down to the boat people looked like black cut-outs against the light, or like my mother in a photo that shows her in silhouette, her arms full of narcissi, next to the boat with its lateen sail. Against all odds, Im convinced I was born the night that photo was taken.

The upper Adriatic region had left the Austro-Hungarian Empire some ten years earlier and my parents measured time according to before the war and after the war. The war was behind them; in the photo album I find tiny photos of crippled airplanes, ruined houses, a lopsided Byzantine cupola, maybe in Serbia, maybe in Hungary. The inscription on the front of a little collection of photos of my mother is in Hungarian: Anitanak, 1917: the first one is of her at sixteen standing at the wheel of a warship, wearing a wide pleated skirt and a sailor jacket, the wind in her face. Mother never showed me this album; maybe it belonged to a sweetheart. I found it among her things after she died. It belonged to the time before I existed and which was forever denied me. When we are little, it hurts to be denied the past as it does the elderly to be denied the future. The war acted as a marker of time and it remained that way until the personal disaster of 1929 imposed another one on us. Father and Mother showed no signs of nostalgia for the past; they had been irredentists, good-for-nothing Italy had let them down, there was no empire in Trieste looking down upon its outlet to the sea and neither Mann nor Mahler visited Abbazia. It remained a frontier land. It slipped to the margins, a little piece of Italy between two wars. If my parents had any regrets, they kept them to themselves. Over time, I think they developed a kind of scepticism, but they werent the sort of people to scream abuse. In the meantime, the mysterious

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Comrade from Milan»

Look at similar books to The Comrade from Milan. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Comrade from Milan and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.