Also by Kenneth D. Ackerman

Young J. Edgar: Hoover and the Red Scare, 1919-1920

Boss Tweed: The Corrupt Pol Who Conceived the Soul of Modern New York

The Gold Ring: Jim Fisk, Jay Gould, and Black Friday, 1869.

www.ViralHistoryPress.com

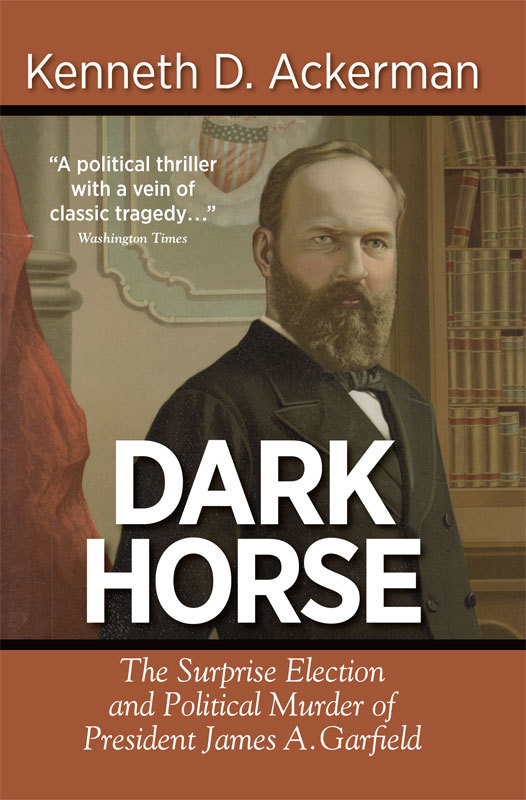

Kenneth D. Ackerman

DARK HORSE

The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield

Viral History Press, LLC

Falls Church, Virginia

Dark Horse

The Surprise Election and Political Murder of President James A. Garfield

Viral History Press, LLC

Falls Church, VA 22044

www.viralhistorypress.com

Copyright 2011 Kenneth D. Ackerman

First Carroll & Graf edition 2003

First Carroll & Graf trade paperback edition 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopyiong, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN-13: 978-1-61945-011-0

Designed by Zaccarine Design, Inc.

eBook conversion by Igossi.com

Printed in the United States of America

Dedicated to my father, William Ackerman, loved and missed by his large family, who taught me that politicians should always stand for justice.

CONTENTS

THE FEUD

April 1866

Starting soon after the Civil War, a Great Feud between two ambitious men would drive American politics for the next twenty years, splitting the Republican Party, shaping three presidential elections, and proximately causing one president to be shot in the back by an assassin, before ruining the careers of both rivals. They were still young when the feud began, in their mid-thirties, but close to emerging as the two dominant political personalities of their time. They would attract legions of followers, known as Stalwarts and Half-Breeds, who would wage great passionate wars on their behalf. For good and ill, their struggle would comprise the politics of the Gilded Age.

Fittingly, the spark that ignited the Great Feud was a matter so small, petty, and avoidable that, had it not been for the contention caused, it would have been soon forgotten. As is, it became legend.

Washington, D.C.April 1866

I move to strike out section twenty of the bill.

The House of Representatives had been debating the Military Bill for four tedious hours when Roscoe Conkling, Congressman from Utica, New York, rose to speak in a clear, loud voice easily heard in every corner. Congressmen in the chamber dropped their chatter. A ripple of attention crossed the visitors gallery above. Conkling cut a striking figure. Self-consciously vain, he stood six foot, three inches tall, with an athletic build, erect posture, and well-muscled arms and shoulders from daily exercise at the punching bag. Conkling enjoyed frequent rides on horseback through Rock Creek Park or along the Potomac River and wore garish ties, trousers, and waist-coats. His sharp eyes looked out from beneath waves of sandy-blond hair, a single curl laid carefully across his forehead. A full beard accentuated a handsome face.

My objection to this section is that it creates an unnecessary office for an undeserving public servant, Conkling continued. It fastens an incubus upon the countryhe stressed the Latin pronunciation IN-cu-bus a hateful instrument of war, which deserves no place in a free government in time of peace. Conkling punctuated his words with sharp jabs of his hands and sweeping waves of his arms, gestures he practiced before a mirror. Only in his third term, the 36-year-old Congressman had made himself a favorite with ladies in the galleries, newspaper men, and sightseers. He peppered his talk with arrogant sarcasm that made opponents wilt.

Section twenty of the Military Bill, which Conkling proposed to delete, authorized the salary and staff of the Provost Marshal General, an obscure Army officer whod been saddled with recruiting soldiers for the Union war effortthe hated Conscription. President Lincolns military draft had sparked riots in New York and other cities during the War. Ugly, drunk mobs had burned, looted, and killed dozens of police and black bystanders. Recruitment bonuses for volunteer soldiers ended up lining pockets of thieves and deserters.

Conkling himself, under contract to the War Department, had prosecuted recruitment frauds in upstate New York in 1864. He had won his cases, and had learned to hate the officer in charge, Provost Marshal General James Barnet Fry. Now he would abolish General Frys office. Conkling on the warpath made good copy. Newspaper men in the gallery opened their notebooks and readied for drama.

Just twelve months after Robert E. Lees surrender to Ulysses Grant at Appomattox Court House had ended the great Civil War, almost every family, North and South, still grieved for lost husbands, fathers, and brothersthe 400,000 killed and millions injured on the blood-soaked battlefields of Virginia, Georgia, and the West. Many Congressmen wore blue Union army uniforms as they milled about the House chamber, joking, smoking cigars, writing letters, spitting into gold spittoons, having no offices beyond the tops of their congressional desks. The chamber, lit by gas-lamps and sky-lights, stank of mold and tobacco amid its marble elegance. Military titles of General, Colonel, or Lieutenant still carried more social grace in Washington, D.C. than did Congressman, Senator, or even President.

The Capitol Building itself looked down over a City of swamps, mud streets, and dank field hospitals. At the far end of Pennsylvania Avenue, Andrew Johnson, the current occupant of the White House, a Tennessee Democrat, was a sad contrast to the martyred Abraham Lincoln. Northern Congressmen despised Johnsons brazen southern sympathies so soon after the War and were fast clipping his wings. They had passed a civil rights bill over Johnsons veto and were finalizing a Constitutional amendment guaranteeing freed slaves the right to vote as citizens, all of which Johnson opposed.

Impeachment against the president would start within the year.

On Capitol Hill, hard-line radicals dominated. All eleven defeated Confederate states had sent members to the 39th Congress, elected in 1865 under President Johnsons liberal reconstruction terms. The unrepentant, all-white delegations included four Confederate Generals, several Colonels and Lieutenants, and even Alexander Stephens, the Confederacys Vice President under Jefferson Davis. These recent warriors now expected co-equal seats in Congress, as if an ocean of blood hadnt been spilled to squash their rebellion. To Union eyes, they were criminals, rebels with fresh murder on their hands and treason in their hearts.

Hard-liners would have none of it. When Congress had convened in December 1865, Republican radicals simply locked the rebels out, deleting their names from the House roll call. As a result, Roscoe Conkling now addressed a House with 191 members, of whom three quarters were Republicans. The majority could impose a reconstruction with teeth and finish the work of the War.

So now, in April 1866, heads turned in the House chamber as Conkling laid out his case against General James Barnet Fry with typical force. General Fry had run an office rife with coxcombs and thieves, Conkling declared. Honest citizens had been victimized by constant uncertainty and deception, millions of government dollars had disappeared, criminals on the Generals staff had stolen money meant for soldiers at the front. Conkling produced a letter from General Ulysses Grant, now serving as Lieutenant General of the Army in the War Department, calling the Provost Marshals office unnecessary. Conkling denounced Fry himself for insolence in office.