Supriya Gandhi - The Emperor Who Never Was

Here you can read online Supriya Gandhi - The Emperor Who Never Was full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 0, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Emperor Who Never Was

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:0

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Emperor Who Never Was: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Emperor Who Never Was" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Emperor Who Never Was — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Emperor Who Never Was" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

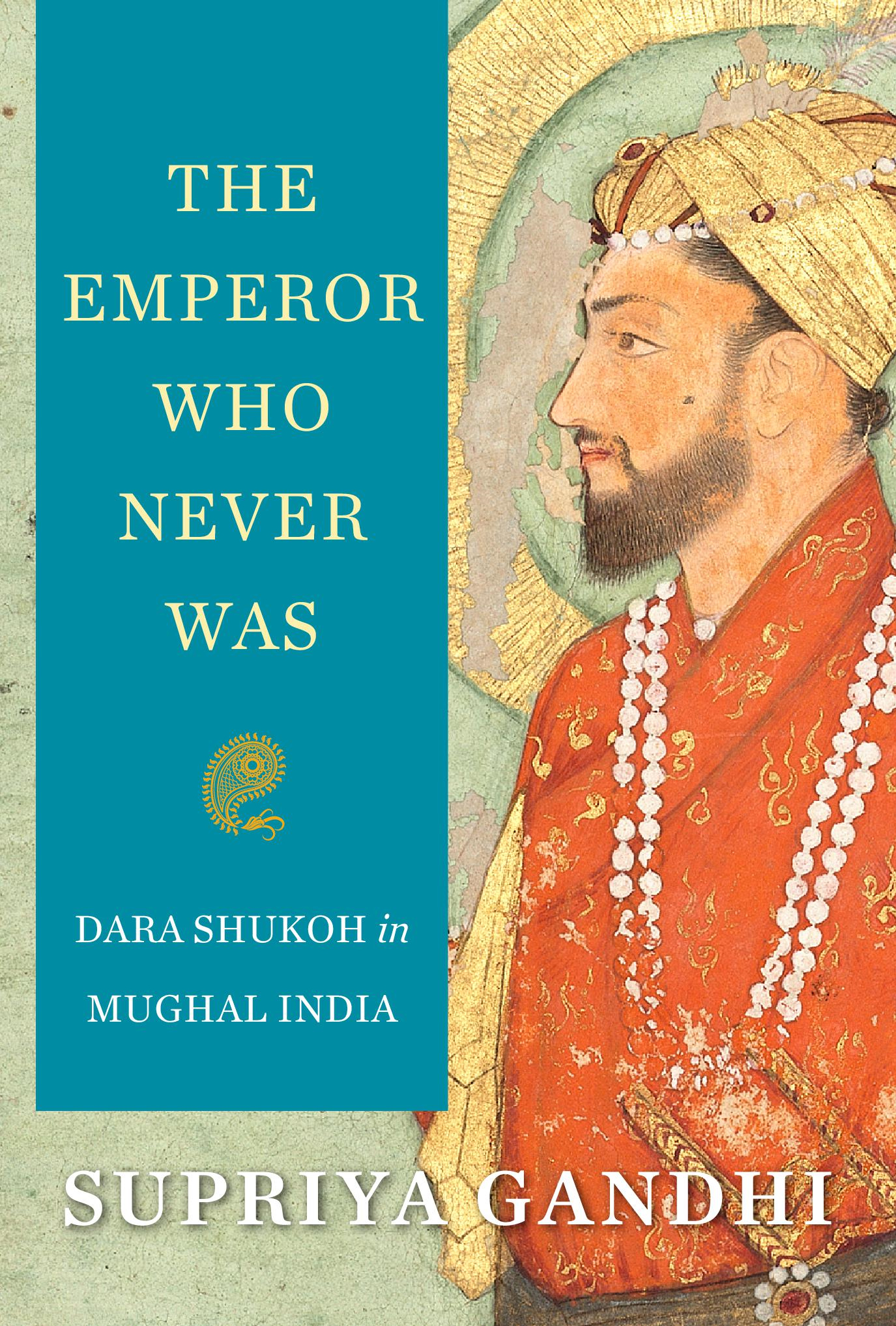

THE EMPEROR WHO NEVER WAS

Dara Shukoh in Mughal India

SUPRIYA GANDHI

THE BELKNAP PRESS OF HARVARD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2020

Copyright 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College

All rights reserved

Cover art: Portrait of Dara Shukoh, mid-17th century, photograph 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

978-0-674-98729-6 (cloth)

978-0-674-24391-0 (EPUB)

978-0-674-24392-7 (MOBI)

978-0-674-24390-3 (PDF)

The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows:

Names: Gandhi, Supriya, 1977 author.

Title: The emperor who never was : Dara Shukoh in Mughal India / Supriya Gandhi.

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2019032493

Subjects: LCSH: Dr Shikh, Prince, son of Shahjahan, Emperor of India, 16151659. | PrincesIndiaBiography. | Philosopher-kings. | IndiaHistory15261765.

Classification: LCC DS461.9.D3 G36 2020 | DDC 954.02/57092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019032493

For ease and elegance, I have eschewed the use of technical diacritical marks for proper names and for Persian, Arabic, Hindi, Urdu, and Sanskrit words. In most cases, I transliterate these in a manner approximating their pronunciation in South Asia. For specialists, the relevant terms and phrases can be reconstructed generally with little ambiguity. Today, Dara Shukohs name is most commonly transliterated and pronounced as Dara Shikoh. However, Dara Shukoh, which I employ here, more accurately reflects the name in seventeenth-century usage during the princes lifetime. I do retain Mughal for the dynasty to which Dara Shukoh belonged. Though anachronistic, the term for the great Indian dynasty is enmeshed in our historical vocabulary for the period.

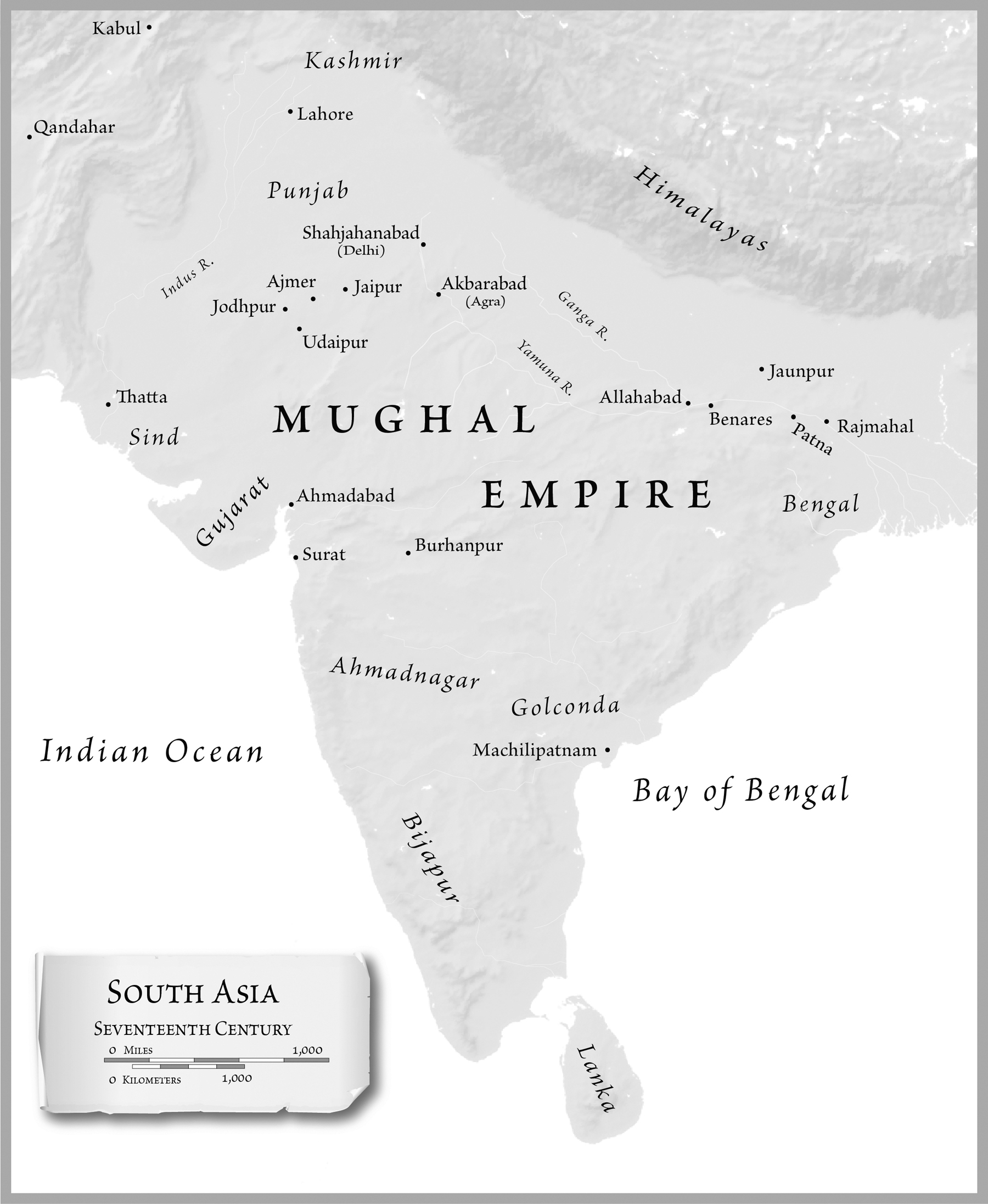

A judge takes his seat in the private audience hall of Delhis red sandstone fort. Only days ago Aurangzeb, the new emperor, had proclaimed himself ruler of Hindustan, choosing the title Alamgir, or world-seizer. The emperor is not physically present in the room, but his authority is palpable. Shadows flicker behind a latticed marble partition, through which imperial women listen to the proceedings, unseen. The trial is about to begin. A prisoner is dragged in, his hands and feet shackled. Dara Shukoh, elder brother of Aurangzeb, stands charged with apostasy.

The prosecutor is unrelenting in his cross-examination. Dara Shukoh, tell us, are you a secret Sikh? And then, So you believe, frankly, Prince, that the Hindu faith is as valid as the Muslim faith? Dara Shukoh eloquently defends his ideas. Who cares which door you open to come into the light? he asks. Finally, the prosecutor orders Dara to present his ring. Damning evidence. It is engraved with Allah on one side and Prabhu, a Hindu word for the divine, on the other. He snaps, Prince Dara, it is unpalatably clear that you strayed, long, long ago, from the pure path of Islam. Shortly after the trial, Aurangzeb orders armed slaves to snuff out his brothers life.

Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb were real historical figures. They were Muslim princes of an Indian dynasty founded in 1526 by their forefather, Babur. Toward the end of his life, Dara initiated a large project of engaging with what we might today call Hindu thought. The prince himself made a comparative study of Hindu and Islamic religious concepts and had the Upanishads, a collection of Hindu sacred texts, translated into Persian. He was killed in a struggle for succession that he lost to his younger brother, Aurangzeb. But there probably never was a trial. At least, the historical chronicles of the time do not speak of one. The scene described above comes from a 2015 theater performance staged in London, adapted by Tanya Ronder from a play written and directed in Lahore by Shahid Nadeem.

Yet the trial has been so integral to the modern story of these two brothers. Mohsin Hamids Moth Smoke, published in 2000, uses the trial of Dara Shukoh as an allegorical frame for his gritty novel about contemporary Pakistan. Akbar Ahmeds 2007 play dramatizes the princes trial by drawing on the authors earlier experience as a magistrate in Pakistan. Many historical novels about the Mughal Empire feature the trial. Even Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi, historian of independent Pakistan, refers to a political trial, of Dara Shukoh, arguing that it was meant to demonstrate to the orthodox that the empire had been saved from a revival of heresy.

The trial is a powerful motif because it transforms a story about seventeenth-century India into a narrative about today. It creates a dialectic between two opposing visions of Islam: Islam as zealous extremism, immediately familiar in our present context, and its counterpointIslam as Sufi antinomianism. But even without the supposed trial, the brothers clash is a story that addresses the deepest questions of who we are and how we got here.

The battle for succession between Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb is an origin myth of the subcontinents present, seen as a crucial turning point in the progression of South Asian history. But it is not a stable myth. Its tellings and retellings shift and settle into the subcontinents fault lines of nation and ideology.

According to one version, Aurangzebs victory over Dara Shukoh cleared the way for Muslim political assertion in the subcontinent. In his 1918 collection of Persian verse, Rumuz-i bekhudi, the poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal, who also outlined an early vision for the state of Pakistan, pronounces judgment on the two brothers. For him, Dara Shukoh represented a dangerous shoot of heresy in the Mughal dynasty that needed to be uprooted: When the seed of heresy that Akbar nourished / Once again sprang up in Daras essential nature / The hearts candle was snuffed out in every breast / Our nation was not secure from corruption.

Iqbal speaks glowingly of Aurangzeb, sent by God to save the Muslim community: Divine Truth chose Alamgir from India / That ascetic, that swordmaster / To revive religion He commissioned him / To renew belief He commissioned him. Aurangzeb here takes on an almost prophetic role. In fact, later in the same poem, Iqbal compares him to Abraham, a foundational prophet of Islam, who smashed stone idols in the Kaaba in order to foster monotheism.

Later, after the new nation-state of Pakistan was born, Ishtiaq Husain Qureshi wove Dara Shukoh and Aurangzeb into his story of the subcontinents Muslims. Like Iqbals account, Qureshis is teleological. Historical events lead inexorably to the present, all linked by a single thread. Aurangzebs victory over Dara becomes a crucial turning point in the march to a separate Muslim homeland. Qureshi says approvingly of Aurangzeb, Character and ability overcame resources and numbers. This was the hour of triumph for orthodoxy.

In a contrasting version, this fratricidal war is a tragedy. Its outcome becomes the reason South Asias nation-states now bristle with mutual hostility and its societies suffer from religious violence. The columnist Ashok Malik expresses this view in his remarks on Daras killing, saying, It was the partition before Partition Dara Shukoh was killed on an August night 350 years ago, and with him died hopes of a lasting Hindu-Muslim compact.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Emperor Who Never Was»

Look at similar books to The Emperor Who Never Was. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Emperor Who Never Was and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.