To hear the faint sound of oars in the silence as a rowboat comes slowly out and then goes back is truly worth all the years of sorrow that are to come.

Jack Gilbert

Contents

On 23 April 1915 in Mudros Harbour, the Allied troopship HMT Ionian weighed anchor and steamed out to sea from the small island of Lemnos in the Aegean Sea. It was carrying the men of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) 10th Battalion, heading into their first active deployment, one that would be perhaps the largest amphibious landing ever attempted in modern war.

Running to a tight timetable, during the afternoon of 24 April the HMT Ionian rendezvoused with the Formidable-class battleship HMS Prince of Wales and two escort torpedo destroyers. B and C companies of the 10th Battalion transferred to HMS Prince of Wales and the remaining A and D companies boarded the torpedo destroyers HMS Scourge and HMS Foxhound. Men, administrative staff, weapons, ammunition and equipment were carefully issued, checked and stowed. Already the 10th Battalion was fatefully split into separate companies, with orders to reassemble upon landing. They would have to find each other once they made landfall on hostile terrain of which they knew very little except that there was a beach Beach Z and distant rugged heights: known by the Turks as Sari Bair.

At 3 am on Sunday 25 April, the first wave of scouts and signallers of the 10th Battalion clambered down the cargo nets into cutters, launches or rowboats tethered to steam pinnaces. At carefully timed intervals, sections of men clambered over the rails and tightly gripped the cargo net as they descended. Everything was carried out in complete silence except for the noises of anxious men clambering from ship to rowboat, knocking railings, weapons and equipment dully clunking, and the odd muttered curse as a foot, buckle or rifle muzzle was caught in the net, or as the deck of the rocking rowboat threw them off balance and into the arms of one of their mates.

Once each rowboat was fully loaded with men and cast off, the sailors aboard each of the steam pinnaces took up the slack and pulled away from the safety of the heavily armed HMS Prince of Wales and began towing a line of three tethered smaller cutter rowboats towards the darkened shore. The first wave of men landing in the predawn light would, of course, possess the element of surprise, which would not extend its tactical advantage to those in the following waves for very long. From onboard the destroyer HMS Foxhound, now off the island of Imbros, a fair-haired man anxiously awaited his turn. Private Thomas Whyte of A Company, 10th Battalion, watched as the larger battleships disappeared into the distance.

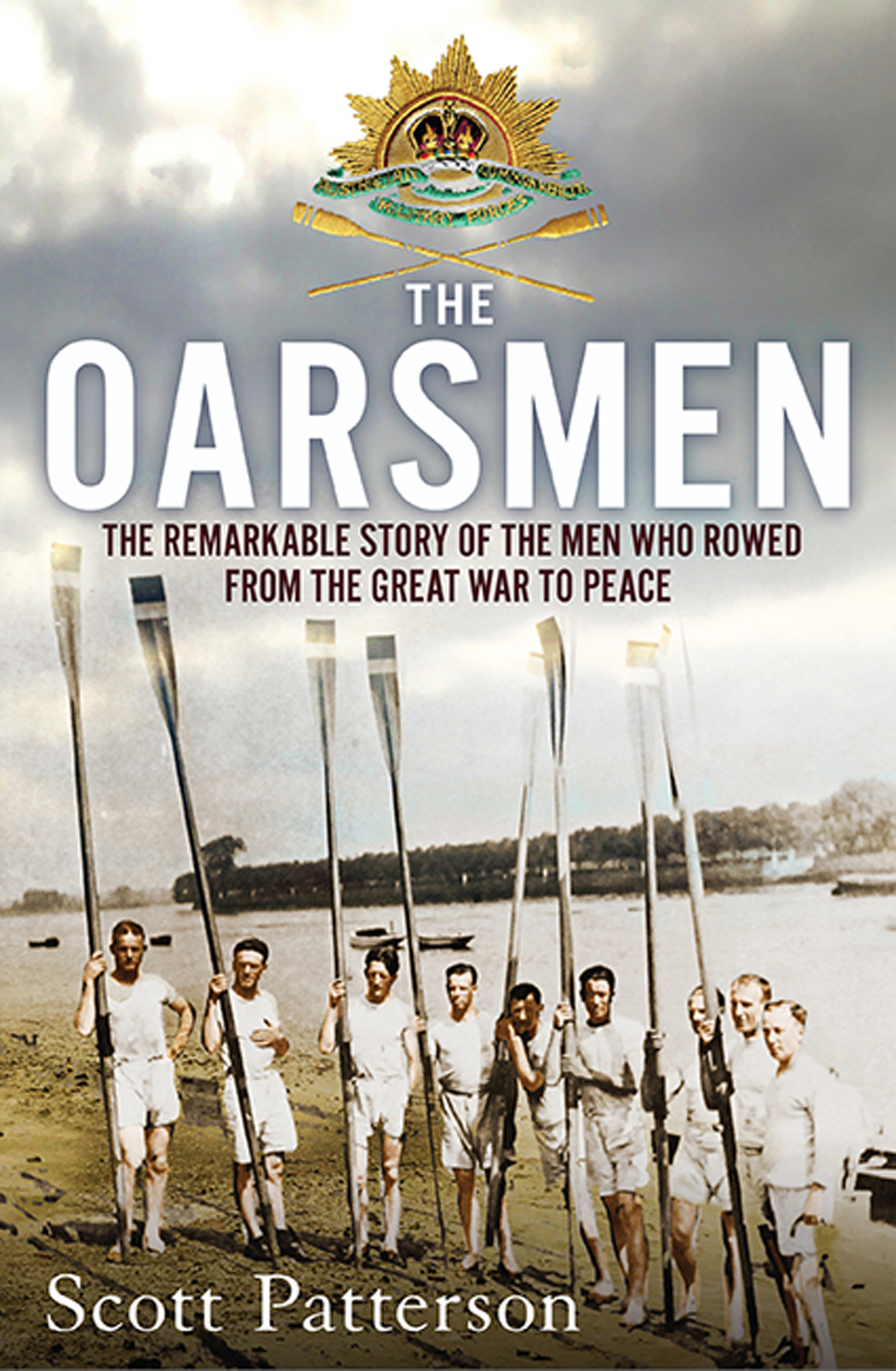

Whyte was an oarsman, with a handsome, weather-beaten face that conveyed intense discipline, and a muscular body in the peak physical condition necessary at the highest levels of competition. But as many sportsmen in those days did, he was no doubt sneaking a cigarette, cupped within his calloused hands to calm his steadily increasing last minute nerves.

Thomas Anderson Whyte was from South Australia. Born in Unley, he attended St Peters Anglican College, Adelaide, and grew into a tall (5 foot 11 inch), robust young man who was very good at sport, including lacrosse, but especially rowing. His oarsmanship, physicality, spiritedness and competitive edge were quickly identified by rowing officials in South Australia and he represented the state time and again in competition in the years leading up to the great war.

Whyte had enthusiastically enlisted within weeks of the declaration of war, along with several clubmates from Adelaide Rowing Club, which he had recently joined, and old St Peters College schoolmates including Arthur Blackburn, who would later be awarded the Victoria Cross.

At twenty-nine, Whyte had life experience and was already engaged to be married to his beautiful young fiance, Eileen Champion. In his letters, Tom frequently signed off with Goodnight, my wife in his mind they were as good as married. Eileen had a steady job as a stenographer and still lived with her parents in Unley Park. Tom and Eileens love and affection for each was very real. In his love letters Tom wrote about his voyage from Australia, the military training and the sights of Egypt, where he was stationed prior to active service, and spoke of their longed-for reunion:

The 3 months I have been away seem more than 12. I build castles in the air every day about our reunion. When I get back, I am not going to think of work for a month and you will have to have a months holiday even if it means the sack.

After weeks of apprehension, when word came that the 10th Battalion were to finally embark for the peninsula, Whyte tried to imagine what the upcoming deployment against the Turks would be like:

Wont it be eerie in the dark creeping towards an enemy. What tricks our nerves will play and then in the morning with their artillery harassing us and our ships guns flying overhead. I wonder what it feels like If I get through alright well and good if not well its the Buddhists nirvana for me and you bear the sorrow. Thats the cruellest part of war those that are left. Still it is the greatest sorrow that heals in time.

On the day before the landing, from onboard the HMS Foxhound as it cruised the peninsula beside the battleships, Whyte wrote to Eileen about his growing anxiety and unease about the uncertain days ahead.

My Dear Sweetheart, I thought of writing this in case I went under suddenly May this letter never be necessary. But the thought that hurts worst of all is of you and your sorrow Just think of me as non-existent in spirit, blotted out completely It would soften the last thoughts if I knew you would be really happy again Goodbye my love, may you get all the happiness you deserve, that will be my last wish.

The story of Gallipoli has been told well and perhaps too often. What occurred in the predawn hours of 25 April 1915 and throughout the remainder of that manifestly Australian longest day is mythic. Troops arrived in a steady stream throughout the morning, afternoon and well into the evening, conveyed from transports to steam pinnaces to rowboats, before splashing into the water and stumbling over the slippery pebbles of Anzac Cove or North Beach.

There, they either dumped gear on the beach before racing up narrow, treacherous ravines blindly following the shouts and tumbling loose gravel of others; or they huddled on the beach in confused groups, cowering under intense Turkish shrapnel, waiting for comrades and orders before anxiously following the steady stream of men up the slopes of Sari Bair, believing there was now some kind of order to the madness.

It is worth acknowledging how the first Anzacs in their first major engagement of the Great War met their destiny: with the skills, courage, sweat and blood of trained oarsmen, who rowed their way into Australias national psyche and collective identity.

In the days and weeks stationed aboard the HMT Ionian at Mudros Harbour, the oarsmen had practised boarding and rowing the boats around the anchored troop ships and destroyers, getting a feel for the weight of these clunky metal and wooden boats. The naval midshipmen spent hours coaching them from the boat, issuing orders such as oars up and easy and working on the timing of their strokes. Thomas Whyte and his experienced band of 10th Battalion volunteer oarsmen became the uber oarsmen around Mudros Harbour. They water taxied top brass from ship to shore, rowed errands and messages between transport ships, delivered supplies and ferried troops ashore to camp. Sometimes the conditions in Mudros Harbour were rough, but Whyte and the oarsmen were expected to row in any conditions.