A LSO BY I AN B URUMA

Their Promised Land: My Grandparents in Love and War

Theater of Cruelty: Art, Film, and the Shadows of War

Year Zero: A History of 1945

Taming the Gods: Religion and Democracy on Three Continents

The China Lover: A Novel

Murder in Amsterdam: Liberal Europe, Islam, and the Limits of Tolerance

Conversations with John Schlesinger

Occidentalism: The West in the Eyes of Its Enemies

Inventing Japan: 18531964

Bad Elements: Chinese Rebels from Los Angeles to Beijing

Anglomania: A European Love Affair

The Missionary and the Libertine: Love and War in East and West

The Wages of Guilt: Memories of War in Germany and Japan

Playing the Game: A Novel

Gods Dust: A Modern Asian Journey

Behind the Mask: On Sexual Demons, Sacred Mothers, Transvestites, Gangsters, Drifters and Other Japanese Cultural Heroes

The Japanese Tattoo

(text by Donald Richie; photographs by Ian Buruma)

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguin.com

Copyright 2018 by Ian Buruma

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

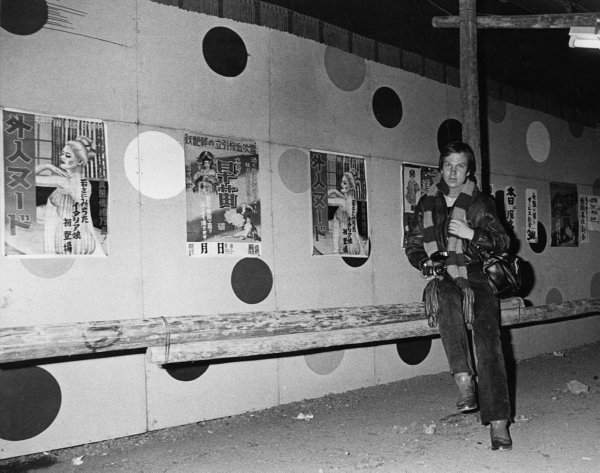

Photographs by the author

ISBN 9781101981412 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781101981429 (e-book)

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the authors alone.

Version_1

In memory of Donald Richie, Norman Yonemoto, and Terayama Shuji

CONTENTS

Cultural initiation entails metamorphosis, and we cannot learn any foreign values if we do not accept the risk of being transformed by what we learn.

Simon Leys, The Hall of Uselessness, New York: NYRB, 2011

ONE

The last thing he said to me, before I closed the door of his smartly decorated loft apartment in Amsterdam, was to stay away from Donald Richies crowd. This was in the summer of 1975. I cant remember the name of the man who offered this advice, but I have a vague memory of what he looked like: close-cropped gray hair, hawkish nose, an elegant cotton or linen jacket; midsixties, I guessed, a designer perhaps, or a retired advertising executive. He had lived in Japan for some years, before retiring in Amsterdam.

Donald Richie introduced Japanese cinema to the West. I knew that much about him. That he was also a novelist, the author of a famous book about traveling around the Japanese Inland Sea, much praised by Christopher Isherwood, and the director of short films that had become classics of the 1960s Japanese avant-garde I didnt know. But I had read two of his books on Japanese movies and was instantly drawn to the tone of his prose: witty, in a wry, detached way, and polished without being arch or prissy. Reading Richie made me want to meet him, always a perilous step for a fan that can easily end in sharp disillusion. There was not much biographical information on the covers of his books, but his 1971 introduction to Japanese Cinema was written in New York, so I assumed that he was an American.

In any case, I was still in Amsterdam, and Richie was, so far as I knew, in the United States, or possibly in Japan, where I was bound in a month or two, for the first time in my life. My Pakistan International Airlines ticket had been booked. My place at the film department of Nihon University College of Art in Tokyo was secure, as was the Japanese government scholarship that would pay for my living expenses. The thought of moving to Tokyo for several years was intensely exciting but alarming too. Would I be isolated and homesick and spend much of my time writing to people six thousand miles away? Would I come back in a few months, humiliated by moral defeat? I had a Japanese girlfriend named Sumie, who would move to Japan as well, but still.

One of the most appealing features of Richies books on Japanese cinema was the way he used the movies to describe so much else about Japanese life. You got a vivid idea of what people were like over there, how they behaved in love, or in anger, their bittersweet resignation in the face of the unavoidable, their sense of humor, their sensitivity to the transience of things, the tension between personal desires and public obligations, and so on.

Richies fond picture of Japan through its movies was not particularly exotic. But then exoticism had never been Japans main attraction to me anyway. Nor was I interested in traditional pursuits like Zen Buddhism, or tea ceremonies, let alone the rigors of the martial arts. The imaginary characters in the movies described by Richie seemed recognizably human, more human indeed than characters in most American or even European films I had seen. Or maybe it was the common humanity of figures in an unfamiliar setting that made it seem that way. Perhaps that is what excited me most about Japan, which was still no more than an idea, an image in my mind: the cultural strangeness mixed with that sense of raw humanity that I got from the movies, some of which I had seen in art houses in Amsterdam and London, or at the Paris Cinmathque franaise, and some of which I had only read about in Donald Richies books.

I actually stumbled into Japan by accident. Asian culture had played no part in my childhood in Holland, even though The Hague, my hometown, still had a nostalgic whiff of the Orient, since people returning from the East Indian colonies used to retire there in large nineteenth-century mansions near the sea, complaining of the cold and damp climate, missing the easy life, the clubs, the tropical landscapes, and the servants. I liked Indonesian food, one of the few reminders of the recent colonial past, and the peculiar Indo-Dutch variety of Chinese cuisine: fat oversized spring rolls, thick and oily fried noodles with a fiery Indonesian sambal sauce made of chilies and garlic, the delicacy of the original coarsened by the greed of northern European appetites. My fathers elder sister had the misfortune of being sent out to the Dutch East Indies as a nanny just before World War II; she ended up spending most of her time in a particularly grim Japanese POW camp. So no nostalgia there.

Asia meant very little to me. But ever since I can remember I dreamed of leaving the safe and slightly dull surroundings of my upper-middle-class childhood, a world of garden sprinklers, club ties, bridge parties, and the sound of tennis balls in summer. As a child, I was fascinated by the story of Aladdin, rubbing his magic lamp. It is possible that the mix of enchanted travels and faraway lands (he lived in an unspecified city in China) left a mark. The Hague was in any case not where I intended to end up.

Perhaps I was prejudiced from an early age against my native country. My mother was British, born in London, the eldest daughter in a highly cultured Anglo-German-Jewish family, which in my provincial eyes seemed immensely sophisticated. My uncle, John Schlesinger, whom I adored, was a well-known film director. He was also openly gay, and his milieu of actors, artists, and musicians added further spice to the air of refinement I soaked up vicariously. Like many artists, John was both self-absorbed and open to new sensations, anything that stirred his imagination. He wanted to be amused, surprised, stimulated. And so I was always eager to impress, giving a performance of one kind or another, mimicking mannerisms, styles of dress, or opinions that I thought might spark his interest. Of course, despite the posturing, I never felt I was being interesting enough. And recalling my efforts in retrospect is more than a little embarrassing.