PRAISE FOR THE WAGES OF GUILT

It would be difficult to find anyone better suited than Ian Buruma to reflect upon the questions of why these national attitudes should be so different. He is thoroughly familiar with the politics and culture of both Japan and Germany, has traveled widely in both countries, and speaks their languages fluently.

The New York Review of Books

Will fascinate readers even as it recalls painful images. [Buruma] is less interested in finding heroes and villains than in teasing out nuances of national character.

Chicago Tribune

The Wages of Guilt augments [Burumas] body of cultural criticism with a brilliant lucidity that guides the reader through a thicket of varying responses to the historical black hole that has been deemed inconceivable.

The Boston Globe

His knowledge of cultural and intellectual life is impressive. This book reflects interestingly on why Japanese and German attitudes differ so remarkably.

The Economist

Highlights the elusive nature of historical truth, which often takes a backseat to the myth-making needed to soothe the collective conscience.

Cleveland Plain Dealer

A clear portrait of two peoples trying to come to terms with their own unspeakable behaviors.

The Wall Street Journal

THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Copyright 1994 by Ian Buruma

Preface copyright 2015 by Ian Buruma

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

Published by The New York Review of Books, 435 Hudson Street, Suite 300, New York NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Buruma, Ian.

The wages of guilt : memories of war in Germany and Japan / by Ian Buruma.

pages cm. (New York review books collections)

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-59017-858-4 (alk. paper)

1. World War, 1939-1945Moral and ethical aspects. 2. World War, 1939-1945Influence. 3. GermanyMoral conditions. 4. JapanMoral conditions. 5. Guilt. 6. Shame. 7. Ethnopsychology. I. Title.

D744.4.B87 2015

940.531dc23

2014041582

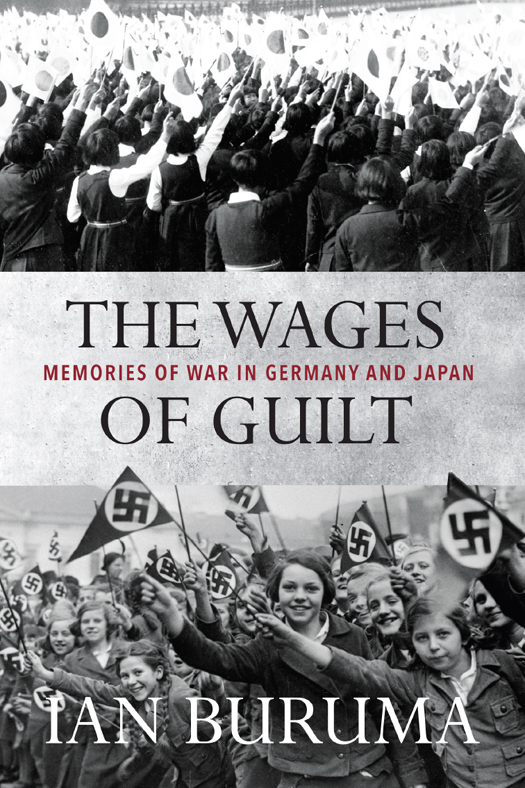

Cover images: Japanese schoolgirls celebrating the capture of the Chinese city of Nanjing in front of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, December 1937 (PhotoQuest/Getty Images); German girls waiting to greet Adolf Hitler, Berlin, September 1938 ( Bettmann/Corbis)

Cover design by Evan Johnston

ebook ISBN 978-1-59017-859-1

v3.1

FOR MY FATHER

Contents

Preface to the 2015 Edition

S OCCER , ESPECIALLY IN Europe, can be a useful way to gauge the state of nations. In 2006, the World Cup was staged in Germany. Apart from Zinedine Zidanes head-butt in the final, the occasion was remarkable for the unselfconscious, festive outpouring of German patriotism. Germans, for good reasons, had been hesitant before to wave their national symbols in the face of the world. This time they did so in such a friendly spirit that no one could mistake it for anything sinister. In 2006, even though their team failed to reach the final, people seemed happy to be German.

It used to be, if you were Dutch, French, Czech, or Polish, that losing to Germany was like being invaded all over again. And the rare victories over Germany were celebrated as sweet revenge. More than half a century after the end of World War II, this feeling seems at last to have evaporated. When Germany won the World Cup in 2014, most Europeans even rejoiced. But then the country visibly was no longer what it once was. The team included two players born in Poland, as well as men of Tunisian, Turkish, Ghanaian, and Albanian descent.

Changing attitudes come with fading memories, even though some historical memories can be lethally tenacious. But I believe there was more to it in this case. When I wrote The Wages of Guilt in 1994, there was still a good deal of fear and distrust of Germanythe economic powerhouse of Europewhose recent reunification was celebrated in the streets of Dresden, Leipzig, and Berlin with raucous cries of We are one people! This sounded ominous to people whose memories had not yet faded, not least to some Germans themselves. But by 2006, Gnter Grasss famous remark that the memory of Auschwitz should have kept Germany divided forever sounded even more absurdly self-flagellating than it had in 1989. Germany had been such a good European, safely embedded for many decades in European institutions and NATO, that it seemed churlish to distrust a generation of Germans who were not yet alive when their country was at war. But the main reason why Germans were more trusted by their neighbors was that they were learning, slowly and painfully, and not always fully, to trust themselves.

In the western half of Germany, at any rate, novelists, historians, journalists, teachers, politicians, and filmmakers had already considered the monstrosities of recent Germany history, sometimes obsessively, but often with remarkable openness and honesty. Few German schoolchildren were unaware of their countrys horrors. If anything, some had begun to resent the relentless fashion in which they were sometimes pushed down their throats. There were still, in the twenty-first century, instances of public figures making dubious or tactless statements about the war, but they would be very swiftly taken to task by other Germans. Demonstrations against immigrants, especially Muslim immigrants, were swiftly countered by demonstrations against racism or xenophobia.

The war was never a laughing matter to Germans, nor should it have been. But the fact that a comedy film, entitled Mein Fhrer, made by a Swiss-Jewish director, was a hit in 2008 was probably a healthy sign too. Laughter at their own countrys expense is surely preferable to self-flagellation. To the extent that the darkest chapters in history can be coped with, the Germans, on the whole, had coped.

Why cant the same thing be said with equal confidence about Japan? The Japanese also hosted a World Cup, together with Korea, in 2002. And young Japanese celebrated the unexpected victories of their team of hip young players with the same carnival spirit as the Germans did four years later. Yet the distrust of Japan, in Korea and other neighboring countries, did not go away. For while the flag-waving young looked innocent of bellicose thoughts (or any thoughts about history at all, which was part of the problem), some of their elders, in government and the mass media, still voice opinions about the Japanese war that are unsettling, to say the least. Conservative politicians still pay their annual respects at a shrine where war criminals are officially remembered. Justifications and denials of war crimes are still heard. Too many Japanese in conspicuous places, including the prime ministers office itself, have clearly not coped with the war.

It should have been easier for the Japanese. The war in Asia was savage, to be sure. The sackings of Nanking and Manila, the slaves worked to death on the ThaiBurma railroad, the brutal POW camps from Manchuria to Sumatra, the millions of dead in China: these have left permanent scars on the history of Asia. But unlike Nazi Germany, Japan had no systematic program to destroy the life of every man, woman, and child of a people that, for ideological reasons, was deemed to have no right to exist.