THIS IS A NEW YORK REVIEW BOOK

PUBLISHED BY THE NEW YORK REVIEW OF BOOKS

Copyright 2014 by Ian Buruma

Copyright 2014 by NYREV, Inc.

All rights reserved, which includes the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form whatsoever.

Published by The New York Review of Books, 435 Hudson Street, Suite 300, New York NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

The David Bowie lyrics in are Used by Permission

The Library of Congress has catalogued the hardcover edition of this book as follows:

Buruma, Ian.

Theater of cruelty: art, film, and the shadows of war / by Ian Buruma.

pages cm. (New York Review books collections)

ISBN 978-1-59017-777-8 (alk. paper)

1. World War, 1939-1945Motion pictures and the war. 2. World War, 1939-1945Art and the war.

3. World War, 1939-1945Literature and the war. 4. War filmsHistory and criticism. 5. National socialism in motion pictures. 6. Violence in motion pictures. 7. War in art. 8. National socialism in art. 9. Violence in art. I. Title.

D743.23.B87 2014

791.43658405343dc23

2014005184

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59017-812-6

v3.1

For

Jim Conte

Contents

Introduction

PEOPLE SOMETIMES SAY to me: You write about so many things. I think this is meant kindly and I take it as a compliment. But there is no special merit in writing about a large number of topics, as opposed to mining fewer veins ever more profoundly. I suppose the main reason for my relatively wide range of subjects is that I am naturally curious and easily bored.

Even though the subjects that pique my interest may be diverse, I do, however, have certain preoccupations, or passions, that I return to, like a dog to a favorite tree. (The none too complimentary word Germans use for a dilettante, who pees here, there, and everywhere, like a wandering hound, is Pinkler.) It would do me little good to start going too deeply into the reasons why I go back to certain concerns. That type of self-analysis can easily lead to self-consciousness and turn off the verbal tap.

But a limited number of personal interests have helped to lend a certain shape to this book of essays. First of all, I am fascinated by what makes the human species behave atrociously. Animals kill other animals for food, and some animals turn on their own kind out of rivalry. But only humans commit acts of extreme and often senseless violence, sometimes out of malign pleasure.

This interests me partly because, like most people, I fear violence. And one tries, perhaps illogically, to make sense of violence that appears to have none. Some cope with their fears by looking away. My own tendency is the opposite: when I see a big rat slithering along the rails in the New York subway, I cannot keep my eyes off it, mesmerized by the sight of something I dread.

So it is with other forms of horror: fear and fascination are disconcertingly close. I am not a believer in devils. Evil deeds are often committed by people who have convinced themselves that they are doing something good. When Heinrich Himmler told his audience of SS officers in Posen in 1943 that exterminating the Jews was a necessary duty carried out for the love of our people, he was most probably sincere. No doubt he reveled in his own power, but I dont think he was evil for the sake of being evil. Himmler was not Satan but a repellent human being with the means to put mad and murderous fantasies into practice. And he had millions to do the dirty work, whether out of conformism or bloodlust. Some of these killers, in other circumstances, would have been perfectly normal people who wouldnt have hurt a fly.

I was born five years after the end of World War II in a country that had been conquered and then occupied by Nazi Germany, to a father who had been forced to work in a German factory and a mother who was Jewish, so it was easy when I grew up to take the moral high ground. I was born among the good guys. It was the Germans who were evil. Later, more awareness that German occupation had given license to many non-Germans in Europe to be actively complicit in Nazi crimes began to blur the distinctions between good and bad.

A common fixation among people of my generation, who grew up in the shadow of the war, is how we might have behaved under severe pressure. Would I have been brave enough to risk my life in the resistance? Would I have kept my mouth shut under torture? These are unanswerable questions. But I am less interested in them than in a darker question, which is no easier to answer: What are the chances, in certain conditions, of me behaving atrociously?

The question of how a civilized, highly educated people, like the Germans in the 1930s, could follow a murderous demagogue into an abyss of moral depravity will never let go of me. But I am well aware that those Germans who followed Hitler were not unique. There are no eternal good guys or bad guys. Nor do I do take the easy cynical view that there is an evil Nazi in all of us, waiting to get out. I am convinced, however, that many people, if given the opportunity to wield absolute power over other human beings, will abuse it. Unlimited authority, often cloaked in the moralism of a great cause, leads invariably to the torture chamber.

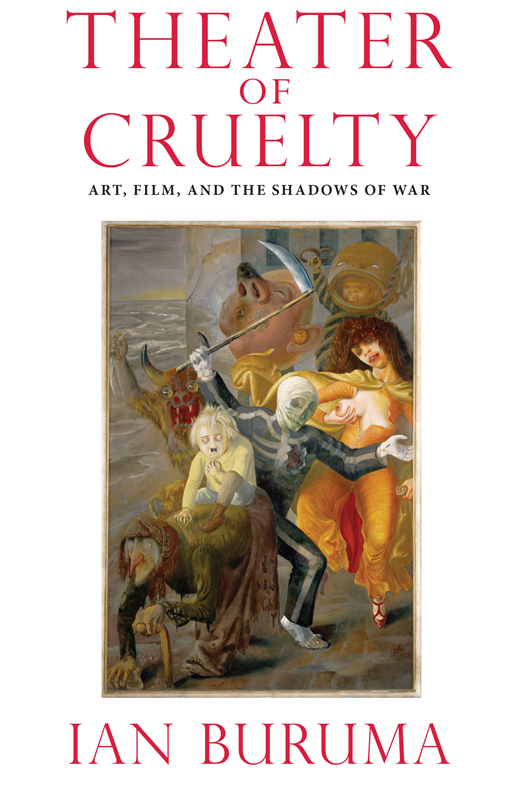

A way to deal with our fearful fascination with power and cruelty and death is to act it out vicariously, in art. Hence the title of this book. This is not to say that all great art or drama has to deal with these sinister themes. But the art and drama that interest me most reveal something of what lies beneath the varnish of what we call civilized behavior. Which is one reason, I suppose, why I love the German art of the 1920s. My favorite artists of that time, such as Max Beckmann, George Grosz, or Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, witnessed the barbarism of which man is capable with their own eyes, in the trenches and field hospitals of World War I and later in the streets of Berlin, a capital made skittish by the horrors of war, poverty, crime, and moral collapse. They looked into the abyss and made art of what they saw.

Germanys wartime ally, Japan, is the other country responsible for some of the worst atrocities in the twentieth century. Many theories have been put forward about the possible reasons why: the samurai spirit, a streak of Oriental cruelty unrestrained by Christian guilt, or a culture of extreme insularity that loses its moral compass outside its own national borders. None of these explanations seems very convincing to me. The barbarism of Japanese troops in China and other parts of Asia arose from a specific set of circumstances, which doesnt excuse the brutality but needs to be properly understood.

My own reasons for spending six years in Tokyo during the 1970s had nothing to do with the war. Not quite knowing what to do at university, I chose to study Chinese language and history, subjects about which I knew nothing. The knowledge I hoped to acquire seemed appealingly exotic and of possible practical use. However, this was in the very early 1970s, when the utility of my chosen subject was not apparent. The Cultural Revolution was not yet over. Contemporary China was almost as remote as the moon. The idea that one might travel freely in China was no more than a fantasy.

While studying Chinese, I saw more and more Japanese films, as well as modern theater productions, in Amsterdam, Paris, and London. Japan looked a great deal more attractive than China in those days, especially for a young man bent on adventure. And so I applied for a scholarship to study cinema at a Japanese film school, which was part of the arts department of a large university in Tokyo.