VIKING

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2020 by Jessica Goudeau

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Goudeau, Jessica, author.

Title: After the last border : two families and the story of refuge in America / Jessica Goudeau.

Description: New York : Viking, 2020. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019033736 (print) | LCCN 2019033737 (ebook) | ISBN 9780525559139 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780525559146 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Women immigrantsTexasAustinHistory. | Immigrant familiesTexasAustinHistory. | American Dream. | Emigration and immigrationGovernment policyUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC E184.A1 G66 2020 (print) | LCC E184.A1 (ebook) | DDC 362.83/98120976431dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019033736

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019033737

All names and identifying characteristics have been changed to protect the privacy of the individuals involved.

Cover design and illustration by Colin Webber

pid_prh_5.5.0_c0_r0

To Mu Naw, Hasna, their family and friends scattered around the world, and the refugee resettlement community in Austinwith all my love.

Where should we go after the last border? Where should birds fly after the last sky?

Where should plants sleep after the last breath of air?

MAHMOUD DARWISH, EARTH PRESSES AGAINST US (TRANSLATED BY MUNIR AKASH AND CAROLYN FORCH)

The world has got very goodvery skilled and very adept, reallyat spotting these great mass abuses of populations. But only from a distance of about 40 years. Up close its different.... The thing about it is that it is happeningnow, to real people. And the worldincluding and especially the world that could helpcant quite get the thing in focus.... This is a question of moral right and international responsibilityand one from which neither the United States nor the rest of the industrial countries should be permitted to look away.

EDITORIAL ABOUT THE INDOCHINESE HUMANITARIAN CRISIS,... AND REFUGEES, THE WASHINGTON POST , JUNE 22, 1979

Contents

Authors Note

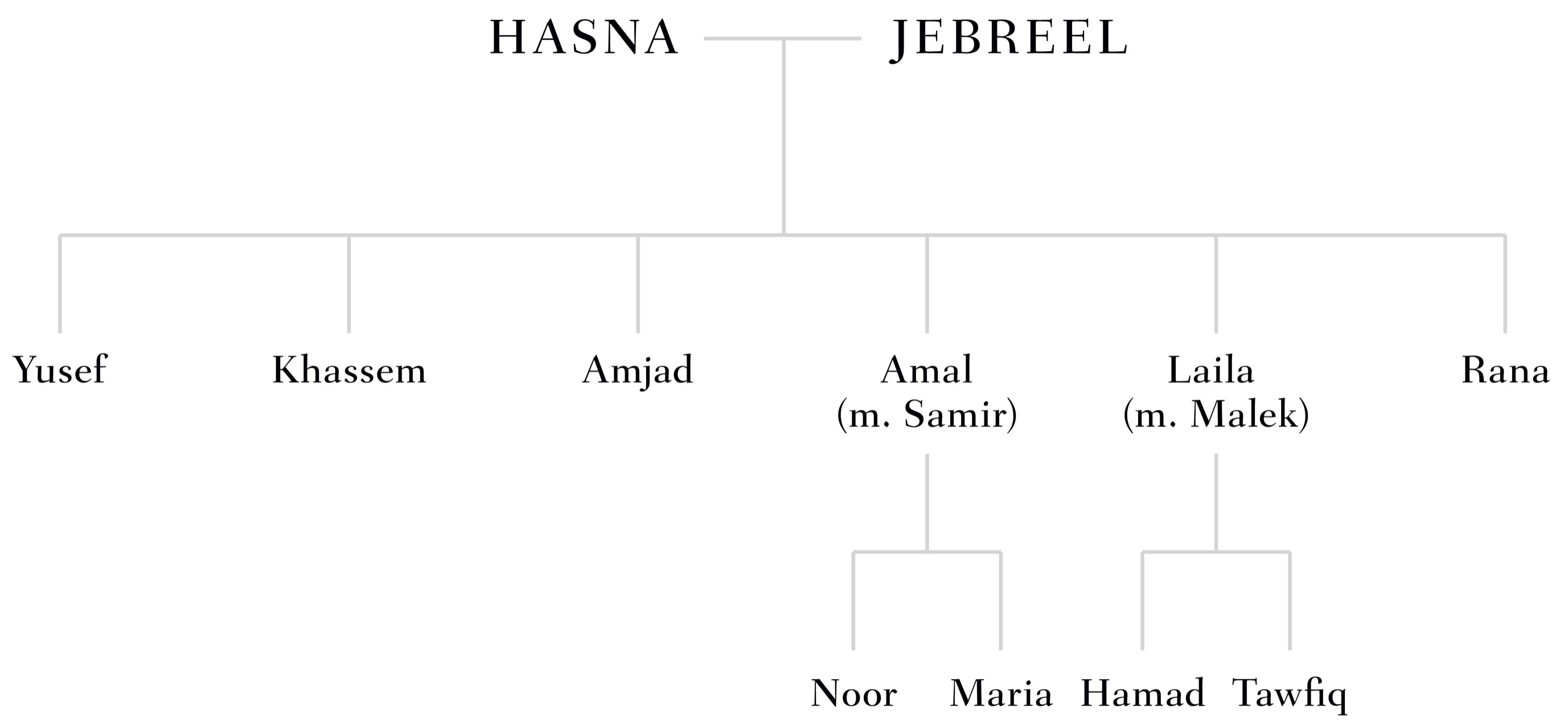

This book tells the stories of two women resettled through the refugee resettlement program to the United States. Mu Naw arrived in 2007, at the beginning of the program for refugees from Myanmar, one of the most successful and widely supported resettlement initiatives in US history. Hasna al-Salam arrived in 2016, with the first wave of Syrian refugees, during one of the greatest moments of upheaval since the establishment of the federal resettlement program.

I gathered the details of these stories through intensive interviews every two weeks or so over a period of two years; in addition, I had been friends with Mu Naw for almost a decade when I began writing the book. The Afterword provides a more in-depth look at our interview process and my methods in writing their narratives. At their request and with their direct input, some identifying details, including names, have been changed to protect Mu Naw, Hasna, and their relatives and friends, many of whom are still in danger currently.

This book is also the story of the American resettlement program itself, from its roots in the immigration debates at the end of the nineteenth century to its dismantling in 2019 at the hands of the government branch that once promoted and protected it. Refugee policy is not a single, monolithic piece of legislation, but a series of programs and practices shaped by one of the most powerful forces in the American republic: the will of the people. Too often we focus on the opportunities the US provides immigrants in the land of the American Dream, and not on how our mercurial national moods lead to small and large policy shifts that radically affect real people. Americans national fight for identitythe wrangling about who we once were, how we will define ourselves for each generation, and who we want to becomeis the single greatest determiner of who we accept for resettlement.

After years of friendship with refugees and countless hours of research into one of the most remarkable, if imperfect, federal programs, I have come to believe that refugee resettlement is a bellwether of our countrys moral centerhow we respond to the greatest humanitarian crises of our time reveals our nations soul.

Prologue

MU NAW

MYANMAR/THAILAND BORDER, 1989

Mu Naw is five and she is running. Thick wet grass rises higher than her chubby thighs and she lifts her legs as if she is marching, almost jumping to keep up with the frantic adults. Her mouth is silent, but her body makes noises because she hasnt learned yet how to run and hide well in the woods. Her mother is carrying her baby sister; her toddler brother is with her aunt. Mu Naw struggles valiantly, pushes back tall plants, breathes hard, but she cannot keep up. Her young uncle swings her up onto his shoulders and she wraps her arms under his neck, lays her cheek on his head to keep it out of the way of slapping branches, and holds on.

They run for three days. On the back trails in the mountains, they encounter another family. They are wary at first, but soon realize they are prey hunted by the same predators. They run together. There is safety in numbers. They pool what knowledge they have. Someone heard there are openings at a refugee camp across the river in Thailand. They set off in that direction.

At night, in the darkness, in hushed voices, they share their stories.

Mu Naw overhears her young uncle whispering to another man about what happened; he had waited until his sister, Mu Naws beautiful aunt, was out of earshot to speak. Mu Naws beautiful aunt is married. She caught the eye of a soldier in the Tatmadaw; not just any soldier, a dangerous soldier with burnished stars on his green sleeve.

Mu Naw remembers a man with stars on his sleeve. From her uncles whispers, she learns those stars probably mean he was a general in the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar Armed Forces. The villagers are Karen, one of the many ethnic minorities that the Burmese junta is targeting on a variety of fronts. All over the country, everyone who is Karenor Kachin, Karenni, Rohingya, Chin, or many of the other groups of people who are not ethnically Burmesewill run. Or they will think about running. Or they will wish they had been able to run. They will pour into camps in Malaysia and India and Thailand, depending on how the vicious scythe of war cuts through their villages and cities. When the scythe sliced through Mu Naws village, that general held it.