Stephen Bull - World War II Street-Fighting Tactics

Here you can read online Stephen Bull - World War II Street-Fighting Tactics full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:World War II Street-Fighting Tactics

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

World War II Street-Fighting Tactics: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "World War II Street-Fighting Tactics" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

World War II Street-Fighting Tactics — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "World War II Street-Fighting Tactics" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

INTRODUCTION

BLITZKRIEG IN URBAN AREAS

THE EASTERN FRONT, 194144

THE ITALIAN EXPERIENCE

THE US ARMY IN NW EUROPE

GERMANY, 1945

CONCLUSIONS

SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

PLATE COMMENTARIES

Street fighting known today by the acronyms FIBUA (Fighting in Built Up Areas) or MOUT (Military Operations in Urban Terrain) has occurred since biblical times, and one of the first writers to refer to the subject in a tactical context was the Roman author Vegetius. The medieval, early modern and Napoleonic eras offer numerous examples of bloody fighting and appalling massacres in the streets of contested towns. During the 19th century, however, it was the engineering branches of armies that occupied a specialized niche not only in the prosecution of sieges, but in the attack and defence of ordinary civilian buildings. In 1853 a British officer, LtCol Jebb, RE, writing in the Aide Memoire to the Military Sciences, attempted to formulate universal and scientific principles for the conduct of the defence of buildings and villages.

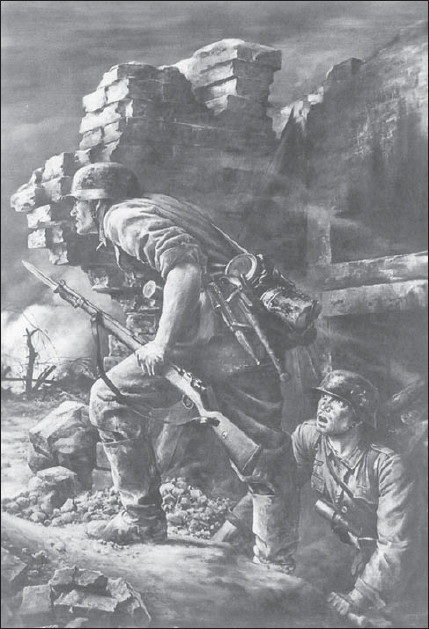

Romanticized impression of fighting amongst ruins, in Will Tschechs wartime painting Grenadiere, once on display at Munichs Haus der Deutschen Kunst.

Jebbs key maxims were: that forces should not be shut up in built-up areas without a particular object; that the means of reinforcement and retreat were as crucial as the actual defence; that buildings required very different treatments depending on their relationship with an overall plan; and that the selection and preparation of any particular structures for defence was a great art, in which one might have to sacrifice almost anything to be successful. When it came to defending a building, Jebb saw little distinction between a church, a factory or a country house all could be made defensible if six factors were taken into account:

A bullet-pocked building in the central Vrhegy district of Buda, 2007. More than 100,000 soldiers and civilians were killed in the battle for Budapest, which began with its encirclement in December 1944, and ended with its fall to the Red Army on 13 February 1945. The German defence centred on the Buda side of the Danube, where a labyrinth of tunnels ran under the ancient castle. About 80 per cent of Budapests buildings were damaged in what came to be regarded as the final rehearsal for the battle of Berlin.

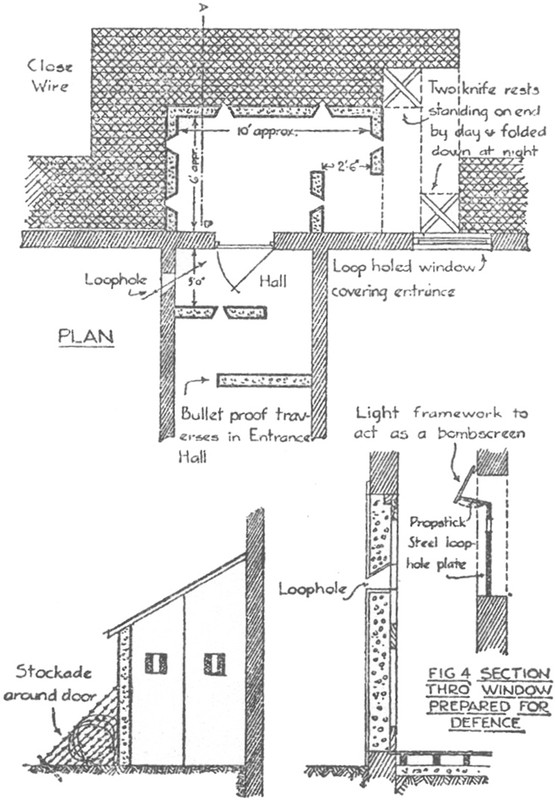

Plan for the defence of a house not exposed to artillery fire, from the British Manual of Field Engineering (1939). The copious use of barbed wire, loopholes, steel loophole plates and traverses is suggestive of lengthy preparation and draws extensively upon devices developed for the trenches of World War I. The thick apron of close wire prevented enemy troops getting close enough to place charges or put grenades through narrow openings.

In 1862 the same journal printed a counterpart article in which Gen Sir John F. Burgoyne elaborated principles for street fighting and the attack and defence of open towns, citing illustrations from both Napoleonic and more recent examples. Burgoynes approach was brutally realistic; he recognized that when committed inside a built-up area, confronted by tumults and insurrection and often unable to tell bystanders from foes, troops were liable to respect neither person nor property. The only satisfactory way to prevent loss of control was therefore not to bring the soldiery into an enemy or rebellious town until they were fully authorized to act. Where facing determined opposition, attackers would do well to deploy sappers provided with an assortment of crowbars, sledgehammers, short ladders, and above all, some bags of powder. These could work their way along continuous terraces of buildings, breaking through walls, while the infantry avoiding column formations fought in small detachments well supported. The infantry could similarly help the engineers by keeping up fire against windows, preventing defenders from shooting out. In some instances burning the whole town had much to recommend it. Many of Burgoynes points would be demonstrated during May 1871, when the French Army of Versailles recaptured the streets of Paris from the rebellious Communards in Bloody Week.

By World War I street fighting had a long and unedifying history, and it was natural that this particular form of combat should be increasingly codified and integrated into formal training. Grenades were standard issue for engineers long before 1914, while the modern flamethrower was perfected in the decade leading up to the war and unleashed in 1915. In Britain, Charles N. Watts published his Notes on Street Fighting in 1916. By this time British Army sniper training included lessons on built-up areas, and realistic environments were specially created for practice. At the end of the Great War, US instructors took the idea a stage further with the introduction of the now-famous Hogans Alley concept. According to Maj J.S. Hatcher, this was originally the brainchild of a Capt Deming, an artist by profession, who had contributed much valuable material to training by creating landscape targets. Back at Caldwell, New Jersey, in 1919, he constructed a French Village. At the back of this was

a pit for the scorers. Each of these scorers had a cardboard figure, resembling the head and shoulders of a man, nailed on the end of a long stick. The shooter took his place at the firing point, gun in hand. Suddenly at the windows or the corner of a wall, or some other unexpected place, one of these figures would be exposed for three seconds, then withdrawn This is a very hard thing to do.

At Camp Perry, the US National Rifle Association would teach similar urban combat skills to police and civilian pistol shooters using this same Hogans Alley idea.

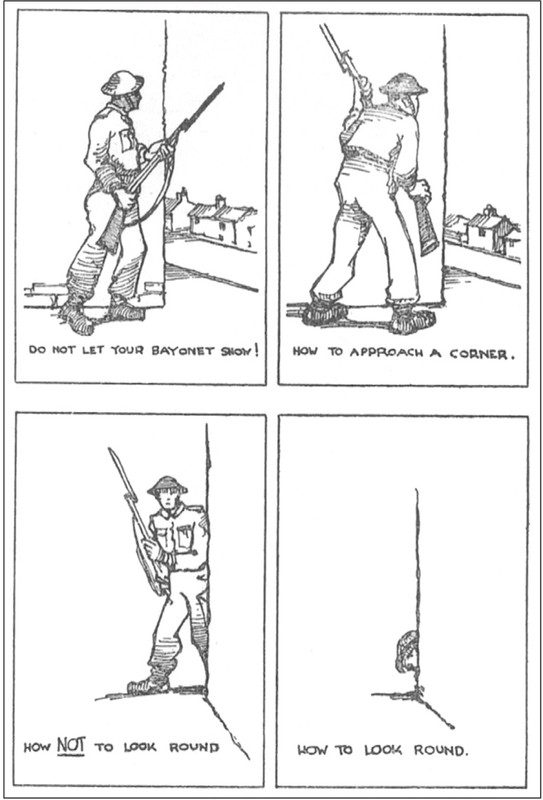

Some basic tips for the infantryman from Maj G.A. Wades House to House Fighting (1940). Again, the drawings are only slight modifications of those produced during 191418 showing troops the correct way to treat traverses during the advance along a trench.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «World War II Street-Fighting Tactics»

Look at similar books to World War II Street-Fighting Tactics. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book World War II Street-Fighting Tactics and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.