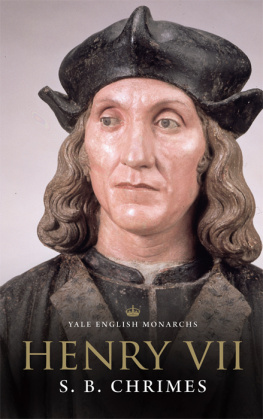

HENRY VII

Also in the Yale English Monarchs Series

ATHELSTAN by Sarah Foot

EDWARD THE CONFESSOR by Frank Barlow

WILLIAM THE CONQUEROR by David Douglas

WILLIAM RUFUS by Frank Barlow

HENRY I by Warren Hollister

KING STEPHEN by Edmund King

HENRY II by W. L. Warren*

RICHARD I by John Gillingham

KING JOHN by W. L. Warren*

EDWARD I by Michael Prestwich

EDWARD II by Seymour Phillips

RICHARD II by Nigel Saul

HENRY V by Christopher Allmand

HENRY VI by Bertram Wolffe

EDWARD IV by Charles Ross

RICHARD III by Charles Ross

HENRY VII by S. B. Chrimes

HENRY VIII by J. J. Scarisbrick

EDWARD VI by Jennifer Loach

MARY I by John Edwards

JAMES II by John Miller

QUEEN ANNE by Edward Gregg

GEORGE I by Ragnhild Hatton

GEORGE II by Andrew C. Thompson

GEORGE III by Jeremy Black

GEORGE IV by E. A. Smith

Available in the U.S. from University of California Press

First published in Great Britain in 1972 by Eyre Methuen Ltd

Reprinted 1977; first paperback edition 1977

This edition first published by Yale University Press in 1999

Copyright 1972, 1977 S. B. Chrimes

New edition 1999 The Estate of S. B. Chrimes

New Foreword 1999 George Bernard

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Printed by Good News Digital Books, Ongar

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-61177

ISBN 978-0-300-07883-1 (pbk)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4

CONTENTS

(by George Bernard)

ILLUSTRATIONS

MAPS

Henry of Richmonds march to Bosworth, 1485

Southern Scotland

Parliamentary England 1439 to 1509

Lands of the Crown in Wales in the reign of Henry VII

Ireland

Northern France and the Low Countries

SELECT PEDIGREES

The Descent and Descendants of Henry VII

The House of York

The House of Valois

The Houses of Burgundy, Hapsburg, and Spain

Maps 2, 5 and 6 are from England under the Tudors by A. D. Innes; Maps 1 and 4 are from An historical atlas, of Wales and are reproduced here by kind permission of the author, William Rees; and Map 3 is from History of parliament, 143971509, by J. C. Wedgwood, reproduced here by kind permission of George Philip & Son Ltd.

All the maps were redrawn by M. Verity.

FOREWORD TO THE YALE EDITION

by George Bernard

Chrimess Henry VII deserves republication. Described by reviewers as sober, sensible, well-structured and magisterial, beyond question the best and fullest account of the reign written so far, it remains the most recent book-length study of the reign. he had a good grasp of the printed sources for the reign, using parliamentary statutes to throw light on a variety of concerns. And he drew skilfully on recent research, in monographs, articles, notably J. R. Landers on bonds and obligations, and unpublished Ph.D. theses, such as R. S. Schofields on parliamentary taxation. Throughout Chrimes has written authoritatively, presenting his conclusions as manifest common sense.

Characteristic of his approach is a tendency to play down the importance and the novelty of Henry VIIs reign. That the Welshness of Henry VII has been exaggerated is Chrimess opening gambit. The rebellion of 1487 did not shake Henrys throne. There was nothing of an innovatory nature in parliaments. The laws passed in the reign were hardly of sufficient novelty or substance to confer on Henry any great reputation as a legislator. It is difficult to find much evidence that Henry VIIs government attained any marked success in tackling the perennial problems of law enforcement. In economic and social matters Henry had no consistent policies and took few measures in those fields that were not conventional or repetitious; Henrys relations with the papacy and the church were in no way remarkable. On the face of it, this might seem peversely negative, calling into question the purpose of the book.

Instead, he treats the very uneventfulness of Henrys way of ruling as developing from the achievement of mere stability into a steady pur-posefulness that served as a springboard for what he presents in his final pages as the fluorescence of Tudor England.

Chrimess book deserves republication not simply for its merits as an history of the reign, but also as an historiographical document in its own right. It is a fine late example of a style of historical investigation and writing whose heyday was in the middle third of the twentieth century. It reflects a belief in the importance and the beneficence of public administration, no doubt sharpened by Chrimess own experiences as a civil servant during the Second World War. What mattered were the structures and instruments of what were treated as government departments. It is revealing that the Festschrift presented to him on his retirement comprised a series of studies of the actions of British government and administration ranging from the tenth to the twentieth centuries, and including discussion of the hundred, the justiciarship, the collectors of customs. No doubt historians writing today are more cynical about the effectiveness and the disinterestedness of governments.

Moreover for all his emphasis on stability and on government treated as administration, Chrimes was too scrupulous an historian not to deal with the emergencies and excitements of the reign, even if they are understated, and sometimes seem to qualify his claims. He devotes a full chapter to the pretenders and plotters against the usurper king, though treating their failure as inevitable (the career of Perkin Warbeck had to run its course), and thus minimizing the sense of emergency that characterized the reign, especially its first half. He drew on Landers research on bonds and obligations, considered the vexed question of whether Henrys character deteriorated into avarice as he grew older, and came close here to admitting, against the thrust of his overall purpose, that Henry VIIs regime was becoming destabilized, indeed verging on tyranny, in the late 1500s.

Some seven or eight years after the completion of his book in July 1972, Chrimes offered an assessment of significant contributions made by scholars since. He did this piecemeal, point by point, rather than in any reassertion or development of

In the twenty-six years since Chrimes wrote, there has been relatively little on the details of administrative institutions on which Chrimes concentrated. David Starkey has argued for the conscious erection of a new department, the Privy Chamber, in 1495 following the execution of Sir William Stanley, though Starkeys chronology has been questioned, and the exact significance of this development in Henrys reign is unclear.revenues (to the point of being able to make huge loans to the Habsburgs in the mid-1500s) without regular parliamentary taxation be explained, not least in the light of the large-scale Cornish revolt against taxation in 1497? How far was Henry seeking to extend royal rights against his leading subjects, by exploiting his rights over them as their feudal lord?

The most significant writing on the reign has dealt with relationships of power. M. M. Condon offered a perceptive sketch suggesting that in certain respects the power of die Crown and of Crown officials, most of them legally-trained, was growing, but that nonetheless she was struck by a certain superficiality of achievement despite all the auguries of change: an impermanence, a fragility caused in part by the tensions which Henry VII himself created in binding and dividing the ruling elites themselves.

Next page