ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I have been helped by a multitude of people over the course of writing this book. I am enormously grateful to my husband, Michael Carver, for his devotion and more than occasional personal sacrifice. He has displayed enduring patience and given me unfailing support. I owe my family, and especially my mother, Laura Swick, my grandmother, Inice Johnson, and my aunt, Nancy Adkins, special thanks for always encouraging me to cultivate my talents and to persevere.

I have also been fortunate to enjoy the support of a number of friends and colleagues who have provided me with intellectual stimulation, helpful criticism, comfort, and fortification. I would especially like to thank Amanda Hingst, David Spafford, Rebecca Moyle-Lange, Tyler Lange, Purnima Dhavan, Adam Warner, Elena Campbell, Noam Pianko, and Devin Naar for their assistance in reading countless drafts, offering thoughtful feedback, and endlessly discussing material with me. I am also sincerely grateful to Deseree Lyon, Alejandro Salazar, Christa Stelzmuller, Derrick Stansfield, and Ruth Jewett for their years of support and encouragement. A special thanks is due to Nicholas Goode and Jill Henry-Goode for their friendship and for generously housing me while I conducted my research.

I am profoundly grateful to those who have shepherded my research and guided me. I would particularly like to thank Geoffrey Koziol, who has been a constant source of careful attention, excellent insight, sound advice, and optimism. His vast knowledge and steady guidance have enriched my work. I must also offer my sincere gratitude to Maureen Miller, who has provided me with thoughtful criticism, good counsel, and incomparable attentiveness, and to Jennifer Miller, who has shared her astute interpretive insights and given me perceptive guidance. Their honest appraisals and unflagging support have been invaluable. I would also like to thank Joseph Duggan, Martin Aurell, Jean Blacker, John Gillingham, Glyn Burgess, Emily Albu, Peter Damian-Grint, Patrick Geary, To Ruiz, Robert Jordan, Robert Stacey, the members of the University of Washingtons History Reading Group, and the members of the UCLA Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies California Medieval History Seminar for generously reading portions of my work and giving me their time and comments. Their advice has enriched my work, though any errors that remain are entirely my own. And a special thanks is due to John Ackerman of Cornell University Press for his patience in guiding me through the publication process.

Finally, I would like to thank the institutions that made my research possible: the History Department of the University of California at Berkeley, the British Library, the Bibliothque nationale de France, the Bibliothque municipale de Rouen, the Bibliothque municipale de Tours, the Bibliothque municipale de Alenon, and their staffs. I would also like to thank the Graduate Division of the University of California at Berkeley and the University of Californias Office of the President for providing me with the fellowships that financed my research.

Introduction

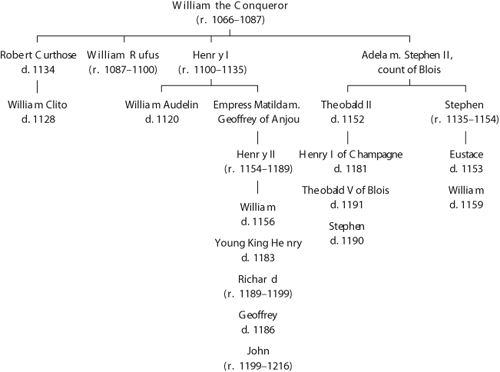

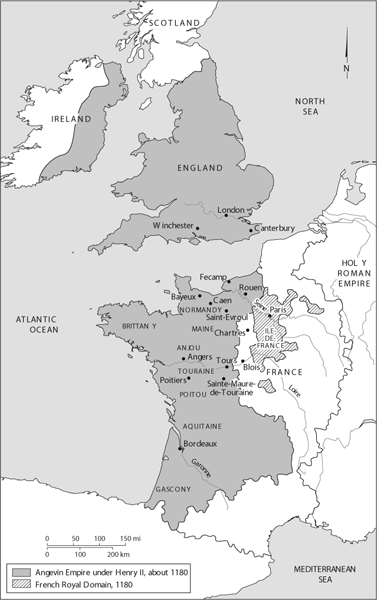

Sometime around 1160, a Norman cleric named Wace began a history of the Norman dukes and kings of England at the behest of Henry II of England (r. 115489). Wace had come to Henrys attention after dedicating an earlier work, the Roman de Brut , to Henrys queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine. Adapting material from various Latin histories, Wace had already completed a narrative that chronicled the deeds of the Norman dynasty from their Viking founder, Rollo (or Rou), to the reign of Henry I when he was abruptly fired around 1174. The reasons for his dismissal are unknown, but Wace was clearly vexed by this turn of events. He complains that he has been replaced by another author in the explicit of his history, the Roman de Rou . Let he whose business it is continue the story. I am referring to Master Beneeit, who has undertaken to tell of this affair, as the king [Henry II] has assigned him the task; since the king has asked him to do it, I must abandon it and fall silent. This Master Beneeit, more commonly known as Benot de Sainte-Maure (author of the enormously popular Roman de Troie and a native of the Touraine), then undertook his own version of the history of the Normans, also at the kings request. Benot dispensed with Waces version of Norman history entirely, and began anew with the Latin sources, eventually producing the Chronique des ducs de Normandie .

On the surface these facts seem unremarkable. What could be more predictable than a king turning to popular authors working in a fashionable style and commissioning a history of his ancestors, presumably in the hope of glorifying his dynasty and himself? This project, however, marked the first time that a medieval European monarch had ever commissioned a dynastic history in Old French. The project was innovative in another sense as well, as works of any kind in Old French had only just begun to appear at the beginning of the twelfth century. Aside from the novelty of the project, Henrys foray into literary patronage also presents us with a mystery: Why was Wace fired?

This book began with a simple question: Why were these histories written? Attempting to answer that question raised countless others. Why were these histories written in the vernacular rather than in Latin? What were Henrys desires for a history of his dynasty and how can we recover them? Did Wace understand his patrons expectations? What did Wace do to provoke the kings ire? Did Benots history satisfy Henry and how can we know? For whom were these histories intended and how did they receive them? We have no records that directly reveal what Henry wanted from a dynastic history or what he may have hoped to achieve by disseminating this history in the vernacular, nor can we fully recover the intentions of either Wace or Benot de Sainte-Maure. Likewise, we have little that directly reveals how audiences reacted to these texts, and nothing that tells us exactly what they thought of them. These problems are agonizingly familiar to medieval historians. In spite of what appears to be a dearth of evidence, we can posit answers to the important questions of political culture raised by these histories by examining the materials that we do have extant: the histories themselves, their Latin sources, contemporary texts, and documents from Henry IIs reign. We are especially fortunate to have two versions of the same history to compare: one that failed to please the king, and one that presumably met his expectations. This experiment in vernacular historiography presents us with a rare opportunity to examine a royal attempt to control the meaning of the past.