Joshua S. Horn - Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969

Here you can read online Joshua S. Horn - Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 1971, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969

- Author:

- Genre:

- Year:1971

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Joshua S. Horn: author's other books

Who wrote Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

An English surgeon in Peoples China:

1954-1969

Introduction by Edgar Snow

New York and London

Copyright 1969 by Joshua S. Horn

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 73-142988

First Modern Reader Paperback Edition 1971

Ninth Printing

Monthly Review Press

62 West 14th Street, New York, N.Y. 10011

21 Theobalds Road, London WC1X 8SL

Manufactured in the United States of America

epub version 1.0

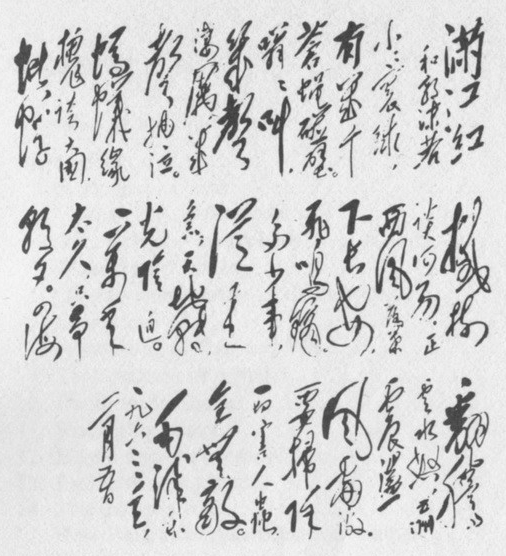

Reply to Comrade Kuo Mo-Jo

to the Melody of Man Chiang Hung

On this tiny globe

A few flies dash themselves against the wall.

Humming without cease,

Sometimes shrilling,

Sometimes moaning.

Ants on the locust tree assume a great nation swagger

And mayflies lightly plot to topple the giant tree.

The west wind scatters leaves over Changan,

And the arrows are flying, twanging.

So many deeds cry out to be done,

And always urgently;

The world rolls on.

Time presses.

Ten thousand years are too long,

Seize the day, seize the hour!

The Four Seas are rising, clouds and waters raging.

The Five Continents are rocking, wind and thunder roaring.

Away with all pests!

Our force is irresistible.

Mao Tse-tung

9 January 1963

Dr Joshua Horns account of his fifteen years as a surgeon, teacher and field medical worker in China is a revelatory and moving book. A man obviously of noble service, his writing impresses us with his own humility and simplicity in contrast to his thoughtful admiration of the people of China transformed, as he sees them, by a great revolution in their environment and thought.

A poor boy himself, who with difficulty won a medical education in England, Dr Horn took honours as a student and on graduation became a lecturer at Cambridge. Tempted there by the promise of a professorship, he turned it down in order to practice medicine in some way he hoped would help poor men become free. He was a humanist with political convictions he sought to express in professional action. After World War II, when he was a surgeon with the British army, he became an outstanding traumatologist at the Birmingham Hospital. Then, in 1954, he volunteered for work in China and uprooted himself and his family, to live in an old world turned upside down.

Dr Horn offers explanations, mainly in the form of a life closely shared with ordinary people, of how Chinese doctors combined theory with practice; how acupuncture, herbalism and traditional medicine are made to play their role along with modern methods; how a mass of peasant doctors, under the direction of mobile medical teams, are trained to diagnose common diseases and on occasion even perform emergency operations in areas inaccessible to hospitals or clinics; how doctors benefit from some manual labour; how the system profits from group consultation, research and experience, in a changing land where highly trained doctors are still in short supply; and how the teachings of Mao Tse-tung are used to encourage and inspire whole communes and even the meekest citizen with hope and a will to act and to serve. By such means Chinas medical workers have, he asserts, conquered or brought under control epidemic diseases, syphilis, leprosy and schistosomiasis; advanced the treatment of severe burns and the reimplantation of severed limbs to the highest levels; won peasant support for planned parenthood; and become first in the world to create synthetic protein (insulin).

Dr Horn leaves no doubt that he himself is a believer in the effectiveness of Maos Thought, but he makes no claims for miracles performed by it. His is no critical report, yet he frankly describes the difficult conditions of work and the material poverty which surrounded him. But in my experience, he writes, very few Chinese regard themselves as being poor The Chinese people have a richer cultural life, are more articulate, use their leisure time more profitably, and have a clearer understanding of where they want to go and how they are going to get there, than any people I have ever met. That makes them rich, not poor. Evidently Dr Horn has made no gold for himself in China and yet clearly he also feels, as a result of his experience there, rich, not poor.

When I was a medical student in the early 1930s the curriculum was strictly divided into two parts. For three years we studied biochemistry, anatomy and physiology. Then for three years we walked the wards, learning the practice of clinical medicine. In retrospect, this separation of theory and practice was most unsatisfactory for the second half of the course seemed to have little connection with the first.

I enjoyed my preclinical studies and managed to collect various prizes and medals which helped keep the wolf from the door. I was short of money for my father was often unemployed, and in those days scholarships were few and niggardly in amount. I earned what I could by teaching and by doing manual work whenever I had the opportunity, but unemployment was widespread and it was not easy to find odd jobs.

I was disappointed that we had no contact with patients but I knew that this would come later on and that then we would be able to use the knowledge we had been accumulating.

I particularly enjoyed anatomy for the human body is constructed with exquisite ingenuity and dissection not only reveals the present stage reached in evolution, but also gives fascinating glimpses of the long process of adaptation and modification which has preceded it. Many structures which became useless as Man evolved, were not discarded but were adapted so that they could play an entirely new role.

The cadavers which we dissected mostly came from the workhouses and they bore all the signs of a life of hardship and deprivation.

Influenced by my father and by the militant struggles of the working class, I entered into the political life of the college, found myself moving towards the left and joined the Socialist Medical Association. Hitler, newly installed in power, was dragging Germany into the depths of savagery and J. B. S. Haldane, a geneticist of renown, with a towering intellect and unshakeable integrity, thundered warnings in the college quadrangle about the rise of Fascism in Germany and at home. Mosleys blackshirts, as arrogant and brutalized as their Nazi models, strutted through the streets of London and fanned flames of racial hatred. The number of unemployed rose steadily; poverty, hunger and insecurity affected the lives of millions.

A great deal of effort was expended in deciding what was the minimum level on which the underpaid workers could live. The British Medical Association appointed an expert committee to determine the nutritional state of the British people and although it set a standard slightly lower than that officially prescribed for Scottish convict prisons, it came to the conclusion that twenty per cent of the entire population lived at or below this level. The Ministry of Health rejected the findings of the British Medical Association on the remarkable grounds that the standard they had set was too high!

Indignant at the wrongness of it all, and wishing to understand and perhaps to influence events, some of us formed a college Socialist Society now a commonplace but then, in my own college, an unheard-of act of rebellion. A young economics lecturer, Hugh Gaitskell, joined the Society. We had one meeting, harmless as it seemed to me, and then the Society was banned by the Provost. Most of us were flattered by being thought dangerous enough to ban and, with open contempt for authority, we continued to meet in the public house across the road. But Hugh Gaitskell left us, never to return.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969»

Look at similar books to Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Away with all pests: an English surgeon in Peoples China, 1954-1969 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.