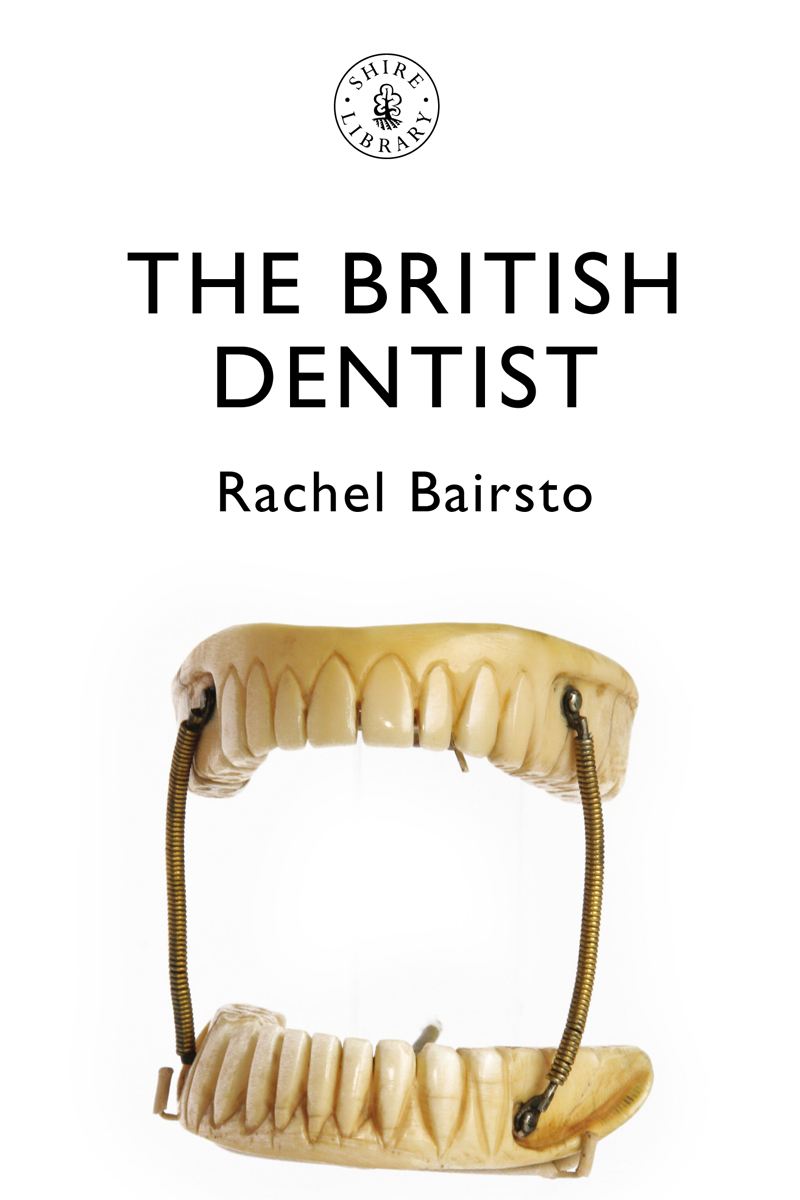

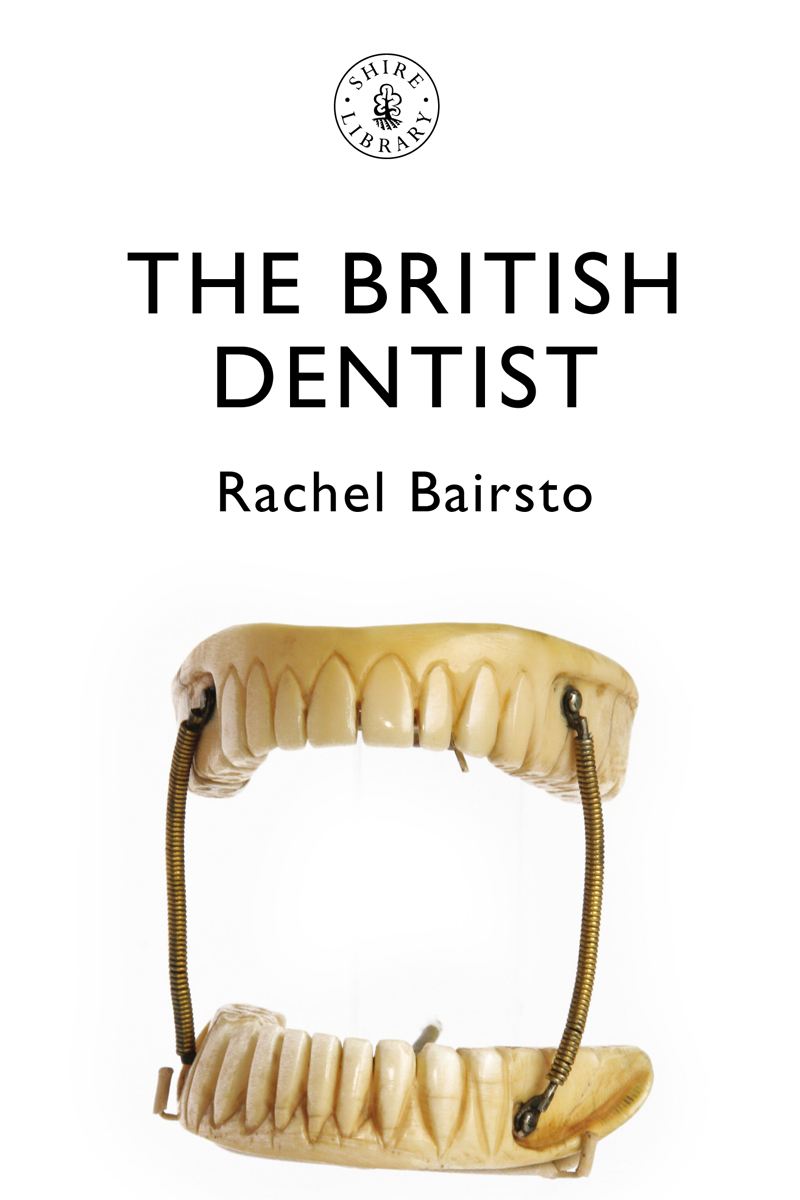

Full set of ivory dentures with piano wire springs, dating from the late eighteenth/early nineteenth century.

This electronic edition published 2015 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Published in Great Britain in 2015 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA.

E-mail:

2015 Rachel Bairsto.

All rights reserved

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 676.

ISBN-13: 978-0-74781-135-0

PDF e-book ISBN: 978-1-78442-080-2

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78442-079-6

Rachel Bairsto has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

Shire Publications is supporting the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity, by funding the dedication of trees.

To find out more about our authors and books visit www.bloomsbury.com. Here you will find extracts, author interviews, details of forthcoming events and the option to sign up for our newsletters.

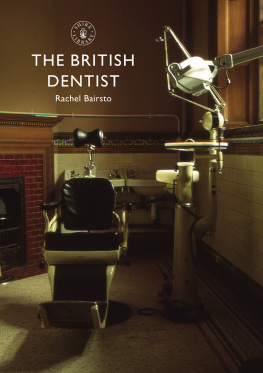

COVER IMAGE

Cover design and photography by Peter Ashley. Front cover: Dentists room at Kinloch Castle, Isle of Rum.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Many thanks to Professor Stanley Gelbier, Honorary Curator of the BDA Museum and Stephen Hancocks OBE, Editor in Chief of the British Dental Journal for their help and excellent advice. Thanks to the photographer of the BDA Museum images, Filip Gierlinkski.

I would also like to thank the people who have allowed me to use the illustrations, which are acknowledged as follows:

The Master and Fellows of Trinity College Cambridge, (bottom). All other photographs are from the British Dental Association Museum Collection.

Instruments used for preparing and carrying out a gold foil filling including gold foil sheets and gold foil pellets, annealing lamp, a variety of pluggers and early automatic mallets.

CONTENTS

FROM TOOTH DRAWER TO DENTIST: 17001800

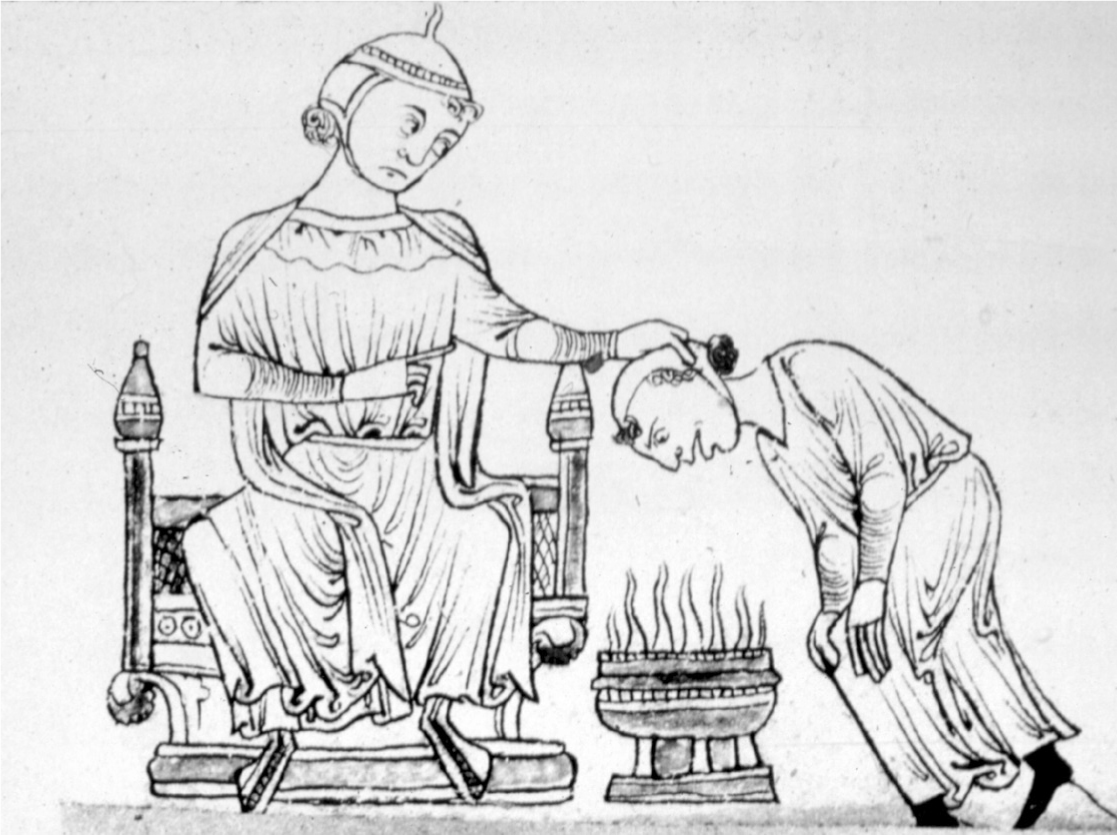

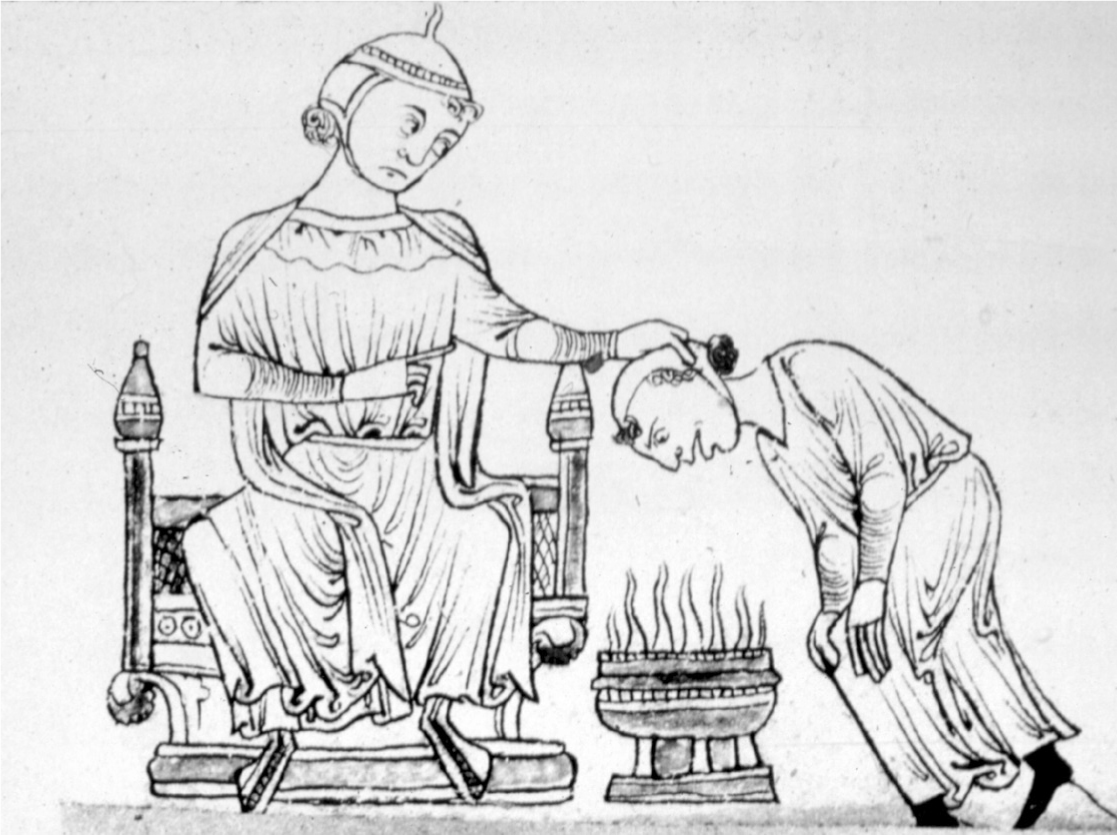

PRIOR TO THE increased availability of sugar in the eighteenth century, tooth problems were most often a result of excessive wear of the teeth from grinding hard, coarse food. In medieval England it was thought that toothache was caused by worms living in the teeth. This was a theory that was to persist until the mid-nineteenth century. It was said that tooth worms could only be eliminated through the fumigation of the mouth by burning henbane seeds over hot coals. No doubt the patient felt temporary relief but the throbbing pain would soon return. Praying to the patron saint of toothache, St Apollonia, was also believed to help the pain and is exemplified by the frequent depictions of her in churches across the country and Europe.

The Tooth Ache, or, Torment & Torture by Thomas Rowlandson, 1823, depicts Barnaby Factotum, who offered the following services: Draws Teeth, Bleeds and Shaves, Wigs made here, also Sausages, Wash Balls, black puddings, Scotch Pills, Powder for the Itch, Red Herrings, Breeches Balls, and small Beer by the maker.

Worn teeth with calculus of an adult male from the Roman period.

Fumigating the teeth with henbane seeds.

A nineteenth-century plaster representation of St Apollonia the patron saint of toothache sufferers.

However, it was the introduction of sugar that was to have a major impact on our oral health, bringing with it a sharp rise in caries (rotting/decay of the tooth) and periodontal disease (disease of the gums and tissues supporting the teeth). Sugar was at first a luxury and so it was often the upper classes in society that would suffer as a result of its use. Queen Elizabeth I herself was said to have blackened teeth caused by her particularly sweet tooth, and also foul breath. Sugar consumption rose dramatically in the eighteenth century as jams, toffee, and other processed foods began to appear more widely on the market. Our delight of sweet food thus created an unprecedented demand for dental treatment.

Ultimately it was the physical pain of toothache that pushed people into seeking out swift treatment. This could be from the local blacksmith always willing to extract a tooth with the tools available to him. In addition barbers and barber-surgeons would not only perform blood-letting, cut hair and shave clients, but also extract teeth. The work of barbers and barber-surgeons was controlled by the guilds, and by 1540 a clear separation was made between the two groups: no surgeon was to practise as a barber and the barbers were to be restricted in their surgical procedures to the extraction of teeth.

The Country Tooth Drawer, copper engraving by William Davison, Alnwick c. 1812. The blacksmith extracts a tooth using a pair of oversized pliers.

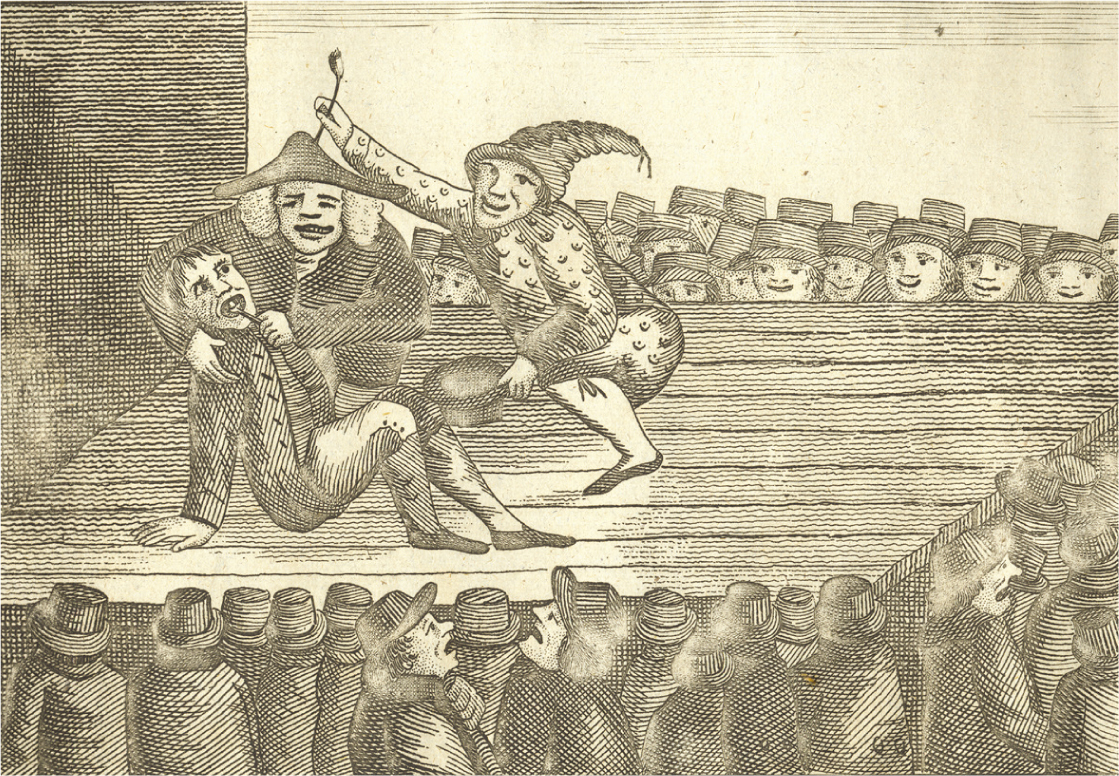

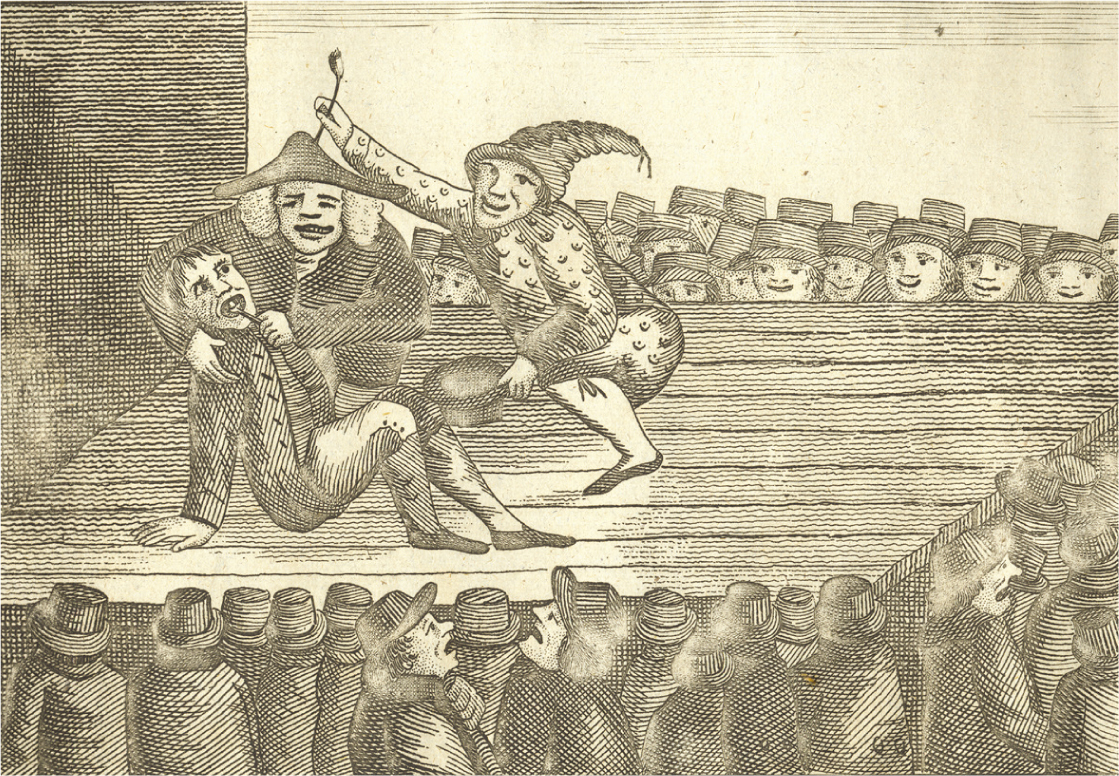

Another option for the desperate patient was a visit to the travelling tooth drawer. He would travel from town to town drumming up trade by erecting a stand at the village market or fair and dressing as a jester, his presence accompanied by loud music. He would often wear a necklace of teeth and teeth were also sewn to his belt. The patient would kneel down or sit on the floor as the operator gripped the head between his knees. He would extract a tooth for a small fee, to the delight of the crowd.

There existed a variety of gruesome-looking tools to aid with extraction. The blacksmith would often use crude forceps, and the surgeon perhaps a more sophisticated-looking instrument called a pelican. The latter used a bolster to grip the gum and a claw that wrapped over the tooth. A swift twist of the wrist ensured the tooth was removed with no uncertain amount of pain. Often the root of the tooth would remain behind and this was either left altogether or the operator would attempt to remove it with a corkscrew-like instrument.

Next page