To my grandchildren, Orden Christopher Mack, Kiara Jolene Mack, and Mya Druscilla Mack. May you live full, unrestricted lives to fulfill the potential I see in each of you

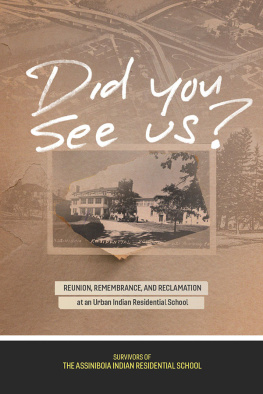

And to all the former students and their families who attended residential schools in Canada, the United States, and Australia

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Foreword

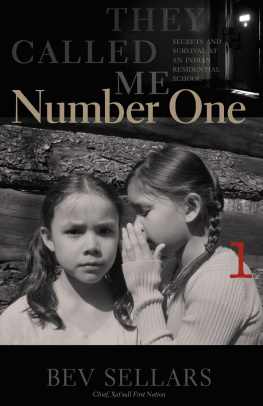

I n this book, Chief Bev Sellars shines light on one of the darkest periods in Canadian history. To me, the residential schools were horrific violations of humanity comparable to the Holocaust and based on the similarly ridiculous assumption that one race and its society are superior to all others. This wrong-headed thinking is the foundation upon which Department of Indian Affairs policy in Canada is based, and nowhere has this stupidity been expressed more blatantly than in the cesspool of mental, physical, and sexual abuse at the residential schools.

I am ashamed to admit that I knew little or nothing about Canadas Brown Holocaust until I was an adult. Thanks to the strength, vision, and wealth of my parents, I did not have to go to the religious prisons. The public school system and idyllic life of the Comox Valley isolated me from the horror and suffering of most Indians my age. I did notice that the kids from the local Indian reserve disappeared every September. I even acted as a driver to take three young relatives to the residential school in Port Alberni. Forgive me for I knew not what I did.

Despite the much-ballyhooed Canadian government apology for residential schools in June 2008 , and the billions of dollars being spent on compensation and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, few people know anything about the collaboration between church and state to destroy races of people and their cultures, a pursuit that lasted more than a hundred years in this civilized country. Genocide in the name of God was the policy that we supported whether we knew it or not.

Bevs story should be part of every school curriculum. All young Canadians need to be exposed to the truth of how generations of innocent children were abused. Such information will change Canadian Indian policy and prevent further atrocities.

My personal ignorance of the schools made it difficult for me to understand the reaction of even the strongest Indian leaders. I remember being inspired by the attitude, rhetoric, and even the oratory of some of my early heroes, only to see them wither in the face of White authority, especially government or the churches. My family taught me to be proud of myself, to stand up for myself, and to look people in the eye when I am speaking to them. Meanwhile, nearly every Indian my age or older expressed shyness, nervousness, and a subservient attitude; I wondered where it came from. The answer now is obvious and is more clearly defined by the courageous writing of Chief Bev Sellars. I look forward to at least another book from Bev, a beautiful, talented, dedicated woman who has taught me so much.

Hemas Kla-Lee-Lee-Kla

(CHIEF BILL WILSON)

Preface

I was seventeen years old, desperate, and tired of trying to fit in. I was so young, yet I felt so worthless. All I could think of was to die. That night, years of abuse and put-downs finally caught up with me. A silly incident was the deciding factor. Although any one of much-worse experiences should have been the trigger, one small incident is all it took. That moment meant life or death, and I chose death. I saw no point in living.

Earlier that day, I had taken my moms bottle of sleeping pills away from her because she had been drinking and had talked about taking her life. As unhappy as Moms life was, I thought she still had reason to live. Now, I held those pills in my hand. I threw them in my mouth, swallowed easily, lay down in the bedroom, and waited to fall asleep. I did not think about others who were worse off than me. I did not think about the family and friends I would hurt. I just thought about how lost and lonely I felt and how desperately I wanted out of this world, a world that seemed to offer only intense unhappiness. It wasnt long before I felt myself going to sleep

I started writing this book in the early 1990 s when our communities first began to explore and deal with the aftermath of the Indian residential schools, in our case, St. Josephs Mission in Williams Lake, British Columbia. I quickly changed my mind when a close relative angrily said to me, I heard you are writing a book. Boy, you better not be writing about me! This reaction caused me to reconsider making my our story public, but I continued putting my thoughts and memories on paper. In 2004 , I decided to finish the book, even if it turned out to be only an historical record for my family. I asked myself, Is it possible to make other people feel what I once felt and understand my message? Is it possible to make others realize the damage they are doing to themselves and to their loved ones? Is it possible to help others by writing about my experiences, or will it only create tension with others who shared those experiences? Should my memories stay just memories?

I concluded that I had to write this book and share with those I know who are suffering the same experiences. In speaking with others, even those who went to residential school in other parts of Canada, I am amazed at how similar our stories are. I am amazed that the treatment of children was so consistently horrific all across Canada and the United States even into Australia. It is as if the various churches running the schools all took the same training program based on abuse, neglect, and corporal punishment. Like other survivors of the residential schools, my experience resulted in a restricted world view, and the oppressive conditions under which I lived reduced my understanding of options available to me. In writing the book, I realized that I am still disassembling the restrictive world in which I once lived.

In the early 1990 s, I went into the local shopping mall in Williams Lake. While there, I noticed a couple of women, fellow students from St. Josephs Mission. I went over to say hello and eventually our conversation got around to my speaking out about the residential schools. One of the women said to me, What pain have you suffered that qualifies you to speak on the schools? I was surprised at her question. I dont remember my response.

How do you measure pain? The woman who asked that question was one of those whose home was completely broken because of alcoholism. Does that make her suffering more than mine? Or was my pain more because the comforts of growing up with caring grandparents meant I knew there was something better at home than the life and abuses we suffered at residential school? Does the fact that I chose not to become addicted to alcohol or drugs disqualify me from suffering? Or was my suffering more because I did not live life in a fog of alcohol and drugs? If I chose to live through it, deal with it, feel the full extent of the pain, and allow myself to grow emotionally and mentally, does that lessen my suffering?

Aboriginal people in Canada have a story to tell, a story most non-Aboriginals dont know about. Many Canadians are unaware of what happened in a country that proudly boasts of being one of the best places in the world to live; a supposedly democratic country where the freedoms and cultures of all are protected and respected. It is the greatest place to live for anyone, except for the original inhabitants of this land, the Aboriginal people.