Spelling in the nineteenth century was far from regular or consistent. On a few occasions, I have modernized spelling for the sake of clarity. In the appendix, I have retained all of Lincolns spelling.

Prologue

It was the spring of 1863, and President Abraham Lincoln faced a chorus of critics after two grueling years of civil war. While Union and Confederate forces fought, the Northern public was becoming increasingly restless. If the North, with a larger army and greater industrial resources, had believed in 1861 they would win the war quickly, by 1863, what was becoming known as Mr. Lincolns war, struggled on with no end in sight.

Within the North, a movement arose that wanted to preserve the Union as it wasthat is, with slavery. A faction of the Democratic Party, known as Peace Democrats or Copperheads, advocated a restoration of the Union through a negotiated settlement with the South. In their protests, they fulminated against Lincoln, charging that he was a tyrannical despot, and the war a means to enlarge presidential power.

That spring, rallies in Northern cities complained of Lincolns handling of the arrest and trial of Clement Vallandigham, a prominent Ohio Copperhead leader. Shortly after a rowdy protest meeting on May 16 in Albany, New York, Lincoln received the Albany Resolves, ten resolutions demanding the president maintain the rights of States and the liberties of the citizen.

As Lincoln began to compose a reply to the protesters, Iowa congressman James F. Wilson entered the presidents office. Observing Lincoln writing at his desk, Wilson expressed his admiration that the president could compose yet another of his eloquent letters from scratch, especially at this moment of heightened anxiety.

Lincoln demurred. I had it nearly all there, he said, pointing to an open desk drawer.

It was in disconnected thoughts, which I had jotted down from time to time on separate scraps of paper. The president explained this was the way he saved my best thoughts on the subject. He told Wilson, I never let one of those ideas escape me.

Lincoln did not want his best thoughts to escape him, but, across the years, they have escaped us. Over his lifetime, Lincoln wrote countless private notes for his eyes onlyscribbled words to capture ideas and insights about the myriad problems and issues he faced. Never expecting anyone else to read them, he left them undated, untitled, and unsigned. While questions remain as to the dates of some of the notes, the identity of their author was never in doubt. We know they all came from Lincoln because of his easily identifiable penmanship: clear and angular in his younger years, then over time gradually smaller and more rounded.

We also know that he himself thought these notes were important. On August 6, 1860, in the midst of that years presidential campaign, Republican candidate Lincoln sent David Davis, his campaign manager, a fragment he had written thirteen years earlier. In 1847, while preparing to take his seat as a Whig in the 30th Congress, Lincoln had set down his thoughts on tariffs and protections on eleven foolscap half sheets of paper. Now, with economic protectionism a plank in the 1860 Republican platform, he stuffed the pages in a large envelope and mailed it to Davis, with instructions to share them only with Pennsylvania senator Simon Cameron. The first Republican candidate for president, John C. Frmont, had lost Pennsylvania in 1856, and Lincoln was determined to win the Keystone State in 1860. In this action, we can see how valuable these notes must have been to Lincoln: They served as repositories for his most important insights.

Despite this, his private reflections have been mostly overlooked by scholars and general readers alike. Perhaps this is due to their scattershot configuration; in print, they are spread across massive, multivolume collections of Lincolns writings. To see them in person is to visit university libraries, the Abraham Lincoln Library in Springfield, Illinois, and an historical collection in the library of a private home.

Engaging with these notes is like entering a world even most history buffs do not know exists. While generations of historians and biographers have written about Lincolns formal speeches and letters, this book is the first to gather and examine these highly personal scraps of writing and, in doing so, to ask: Is there anything new they can tell us about the notoriously private president?

Lincolns law partner William H. Herndon described his senior law partner in Springfield, Illinois, as the most shut-mouthed man who ever lived. Lincoln often seemed a closed book even to his intimates. But in these notes, Lincoln articulates not only his ideas and opinions, but also his feelings and fears in a manner he did not allow in public. Looking at these notes in their entirety presents a fresh perspective on Lincoln just when we believed there was nothing new to say about this monumental leader.

These remarkable notes survived thanks to the efforts of those closest to Lincoln. Only five hours after his death, at 7:22 a.m. on April 15, 1865, his eldest son, Robert Todd Lincoln, who was in Chicago overseeing a federal circuit court, wired Davis, now an associate justice of the Supreme Court: Please come to Washington at once to take charge of my fathers affairs.

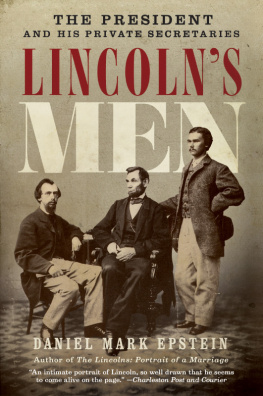

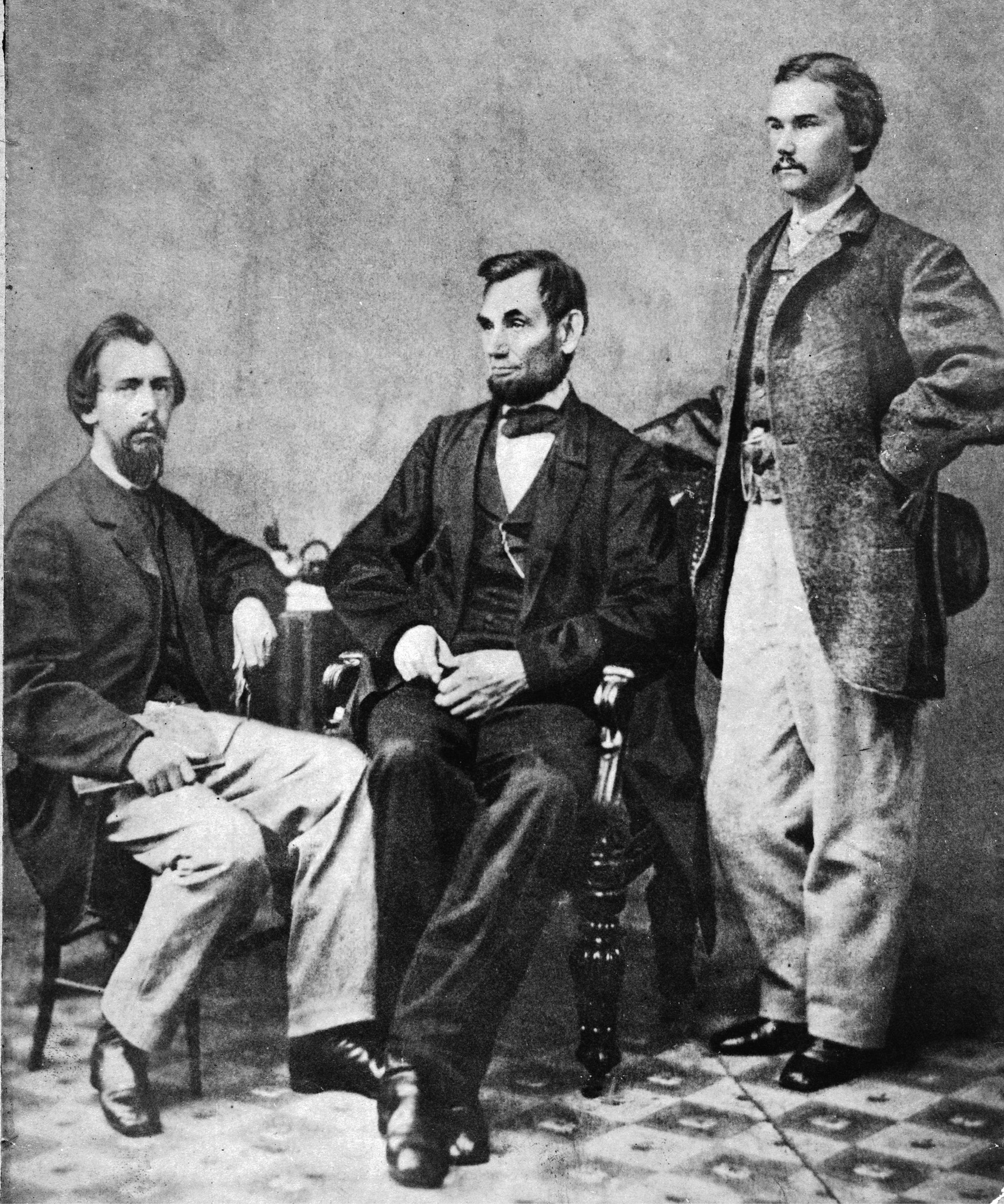

As Davis hurried to Washington, Lincolns two secretaries, John Nicolay and John Hay, worked intensely to collect the presidents papers.

While the nation mourned, Davis arranged for the presidents papers to be shipped to his hometown of Bloomington, Illinois, where they were deposited in a vault at the towns National Bank.

Lincoln sits between his private secretaries, John G. Nicolay, seated, and John Hay, standing, in Alexander Gardners Washington studio on November 8, 1863.

Within weeks of his fathers death, twenty-one-year-old Robert began receiving requests from writers and publishers eager to use the papers to write books on Lincoln. He turned down all of them, and the papers remained under lock and key in the Bloomington bank vault for the next decade.

Robert knew his fathers loyal secretaries had talked about writing a biography as early as Lincolns first term in office, and promised them use of the papers, but Nicolay and Hay would have to wait nearly a decade to actually receive them. When the boxes finally made their way back to Washington in 1874, the two men began their mammoth project.