Robert Forczyk - The Kuban 1943

Here you can read online Robert Forczyk - The Kuban 1943 full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2017, publisher: Bloomsbury Publishing, genre: Non-fiction. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Kuban 1943

- Author:

- Publisher:Bloomsbury Publishing

- Genre:

- Year:2017

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Kuban 1943: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Kuban 1943" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

The Kuban 1943 — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Kuban 1943" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

In April 1942, Hitler announced in his Fhrer Directive No. 41 that the primary objective of the second German summer offensive in the Soviet Union would be the oilfields in the Caucasus. Three months later, Heeresgruppe Sd (Army Group South) split into two sub-commands, with Heeresgruppe A tasked with the main effort to seize the Caucasus, while Heeresgruppe B would attack towards the Volga to seize Stalingrad. Once Rostov was captured on 23 July, Hitler further clarified his objectives in the Caucasus with Fhrer Directive No. 45. Operation Edelweiss, as the invasion of the Caucasus was designated, intended to use the fast-moving units of Generaloberst Ewald von Kleists 1.Panzerarmee (PzAOK 1) to seize the Soviet oilfields at Maikop, Grozny and Baku while Generaloberst Richard Ruoffs 17.Armee (AOK 17) cleared the Kuban, the Taman Peninsula and then the Black Sea coast. Back in Berlin, Hitler believed that Heeresgruppe A could advance over 1,000km by the end of the summer, seizing these critical oil-producing areas, which would then be converted to German use. By depriving Stalin of approximately 70 percent of his crude oil production, Hitler believed that Edelweiss would decisively cripple the Soviet war effort.

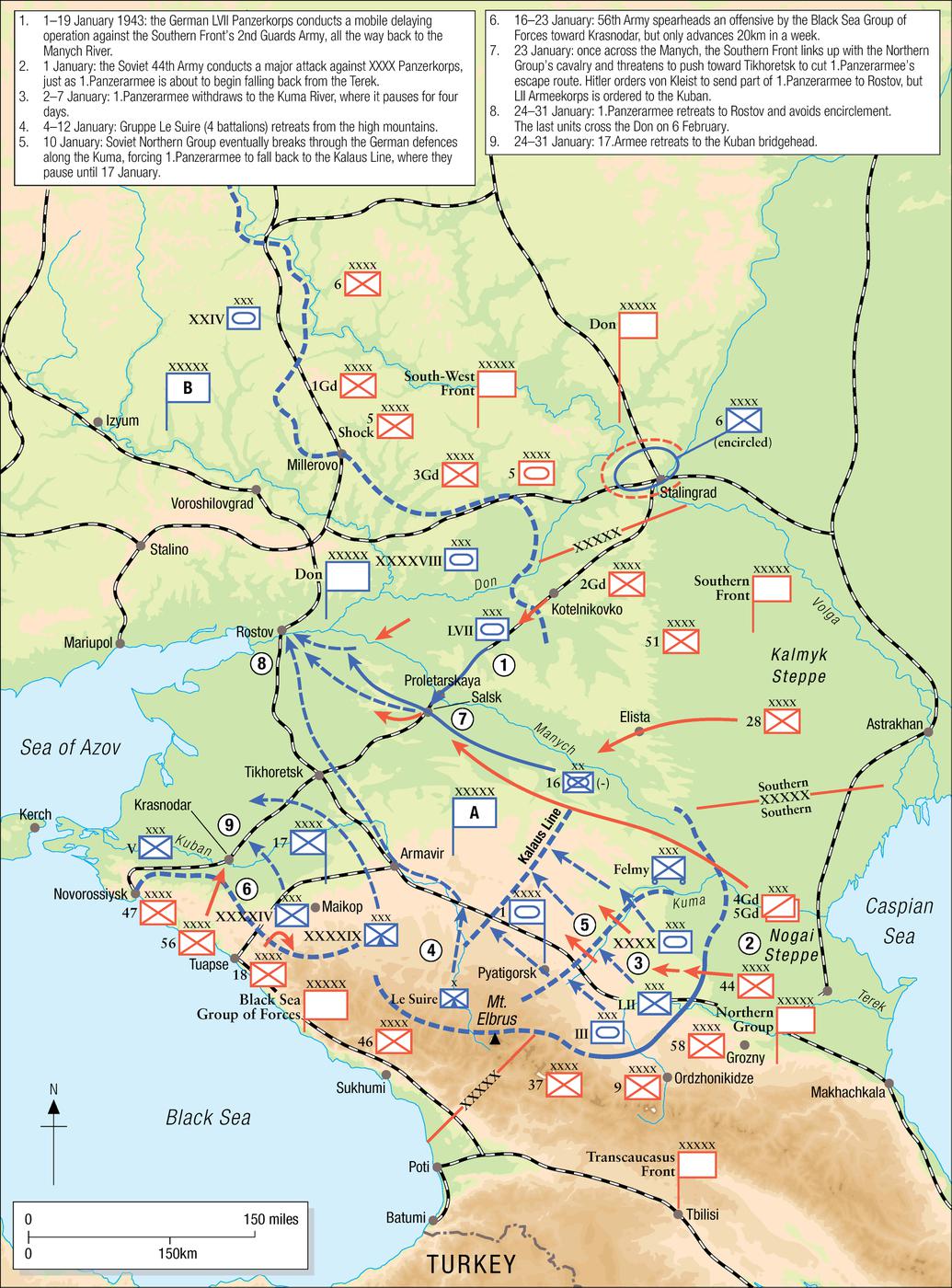

The German retreat from the Caucasus, 131 January 1943

However, what seemed simple in map exercises proved far more difficult to execute in the field. Heeresgruppe A did succeed in invading the Caucasus in July and quickly routed the armies of the North Caucasus Front. While Kleists Panzers captured Maikop on 10 August and pushed south towards Grozny, Ruoff overran the Kuban. In the skies, the Fliegerkorps IV gained local air superiority to support the ground offensive. Yet just when Heeresgruppe A appeared to be on the cusp of victory, Hitler began tinkering with the basic plan: he started transferring forces from the Caucasus to reinforce Heeresgruppe Bs faltering advance towards the Volga. He also failed to transfer three promised divisions of the Italian Alpine Corps to the Caucasus, where they were desperately needed to help clear the Black Sea coast. By October, Operation Edelweiss had run out of steam short of its primary objectives due to increased Soviet resistance and German logistic problems. Ruoffs 17.Armee failed to capture the ports of Tuapse or Sukhumi, despite repeated efforts, and Kleists 1.Panzerarmee was stopped short of Grozny. One final German push in early November resulted in the near destruction of 13.Panzer-Division when it was briefly encircled.

An abandoned PzKpfw III medium tank in January 1943. Note that this tank is outfitted with the wider Winterketten (winter tracks). During the retreat from the Caucasus, Heeresgruppe A was forced to abandon a large amount of its vehicles and heavy equipment. Although this tank suffered battle damage, many vehicles were abandoned for lack of fuel. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-328-2911-21, Foto: Siedel)

For a brief period, the front lines in the Caucasus stabilized and both sides shifted to the defensive. In late November, General der Kavallerie Eberhard von Mackensen took command of 1.Panzerarmee while von Kleist moved up to take command of Heeresgruppe A. This brief period of stasis ended when the Soviet South-West and Stalingrad fronts launched a major counter-offensive, Operation Uranus, on 19 November 1942. Four days later, the German 6.Armee and part of 4.Panzerarmee in Stalingrad were cut off and faced with destruction. In desperation, the Oberkommando des Heeres (OKH) immediately cobbled together a rescue plan known as Operation Wintergewitter, which entailed von Mackensens 1.Panzerarmee transferring the 23.Panzer-Division and the SS-Panzergrenadier Division Wiking to Generaloberst Hermann Hoths 4.Panzerarmee. Much of Fliegerkorps IV was also transferred northwards, which immediately gave the Soviet 4th and 5th Air Armies air superiority in the Caucasus.

Heeresgruppe As position in the Caucasus was quite tenuous and became even worse when Operation Wintergewitter failed in mid-December and the Stalingrad Front (renamed the Southern Front on 1 January 1943) began advancing south. It soon became obvious to both sides that Heeresgruppe A might become isolated in the Caucasus; if that occurred, the entire German southern front in Russia would collapse. Yet Hitler was extremely reluctant to abandon his position in the Caucasus and did not authorize a retreat until 29 December; even then, 1.Panzerarmee was only authorized to retreat 100km from the Terek to the Kuma River line. Hitler optimistically believed that the Kuma position could be held until spring 1943, when he could then mount a new offensive towards the Caucasus oilfields. By holding further south, Hitler also hoped to retain the captured oilfields around Maikop, which had just been repaired.

At the end of 1942, Soviet forces in the Caucasus consisted of two main groupings. General-polkovnik Ivan I. Maslennikovs Northern Group of Forces, in the Grozny and Terek River sector, consisted of four armies (9th, 37th, 44th and 58th) and two independent cavalry corps supported by the 4th Air Army (Vozdushnaya Armiya VA). In the Tuapse sector, General Ivan E. Petrovs Black Sea Group consisted of four armies (18th, 46th, 47th and 56th) supported by the 5th Air Army and the Black Sea Fleets naval air arm (VVS-ChF). The Transcaucasus Front served as a force provider and logistical source for both groups, but did not directly command units in the field. For the Soviets, the Caucasus was a backwater theatre and received far less material support than was going to the main effort in the Stalingrad sector. Nevertheless, Stavka (the Soviet High Command) expected the forces in the Caucasus to drive Heeresgruppe A from the region at the earliest opportunity.

On 1 January 1943, von Mackensens 1.Panzerarmee began its retreat from the Terek River and Maslennikovs four armies immediately launched their long-planned counter-offensive. Maslennikovs pursuit, spearheaded by two cavalry corps and two ad hoc mechanized groups, was poorly coordinated but managed to keep 1.Panzerarmee on the run and prevent it from forming a viable line on the Kuma River. By 10 January, Maslennikovs spearheads were across the Kuma in force. Even worse for 1.Panzerarmee, the Southern Front pushed Hoths forces back over 100km and was approaching the Manych River, which threatened to envelop von Mackensens open left flank. If Soviet armour crossed the river, there would be little to stop it from severing von Mackensens line of communications and cutting off the bulk of Heeresgruppe A in the Caucasus. Amazingly, Hoth managed to fight a two-week delaying operation on the Manych River, which bought time for von Mackensens 1.Panzerarmee to escape the Soviet pincers. Overall, the German retreat from the Caucasus was fairly well managed but still something of a disaster since inadequate fuel supplies caused hundreds of vehicles to be abandoned.

A German 15cm infantry gun is towed during the winter retreat. The 17.Armee lost a good portion of its artillery in the retreat to the Kuban and initially was handicapped by severe shortages of food, fuel and ammunition. Hitler made the decision to defend the Kuban bridgehead because he had no real option to withdraw 17.Armee from the Taman Peninsula before spring 1943. (Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-725-0192-25, Foto: Reimers)

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Kuban 1943»

Look at similar books to The Kuban 1943. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Kuban 1943 and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.