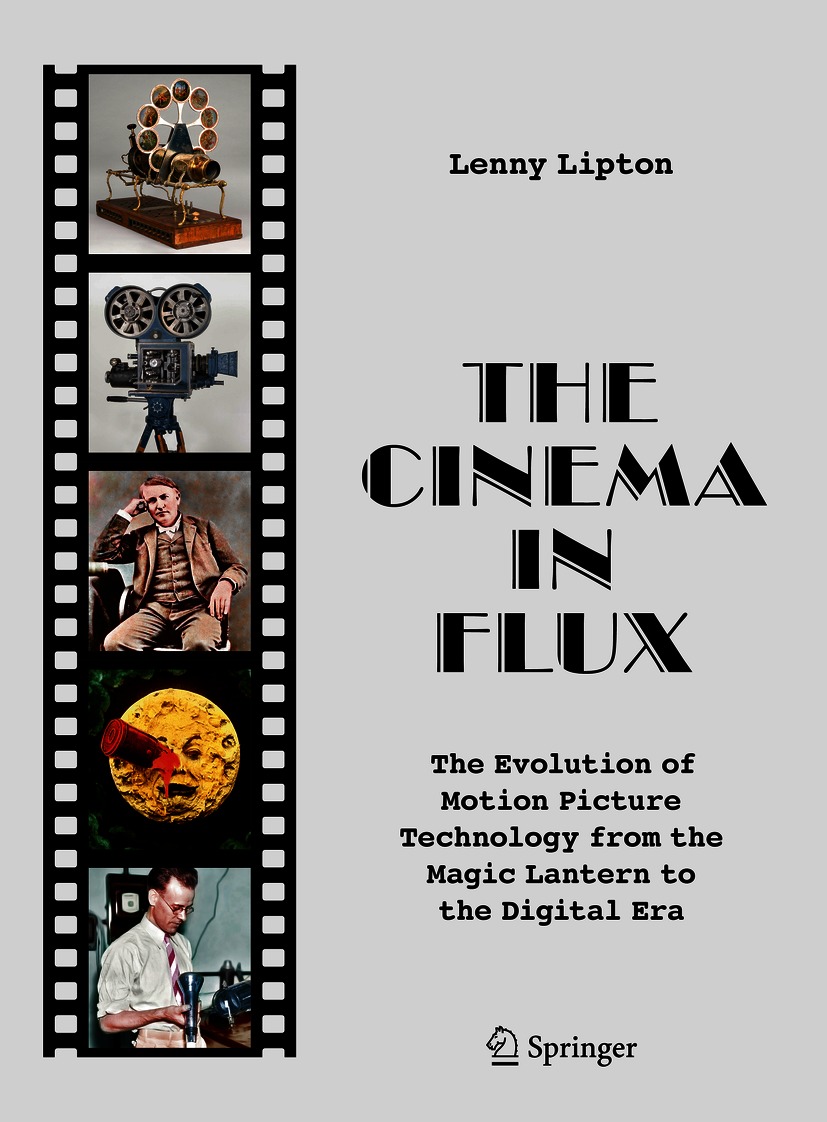

Lenny Lipton

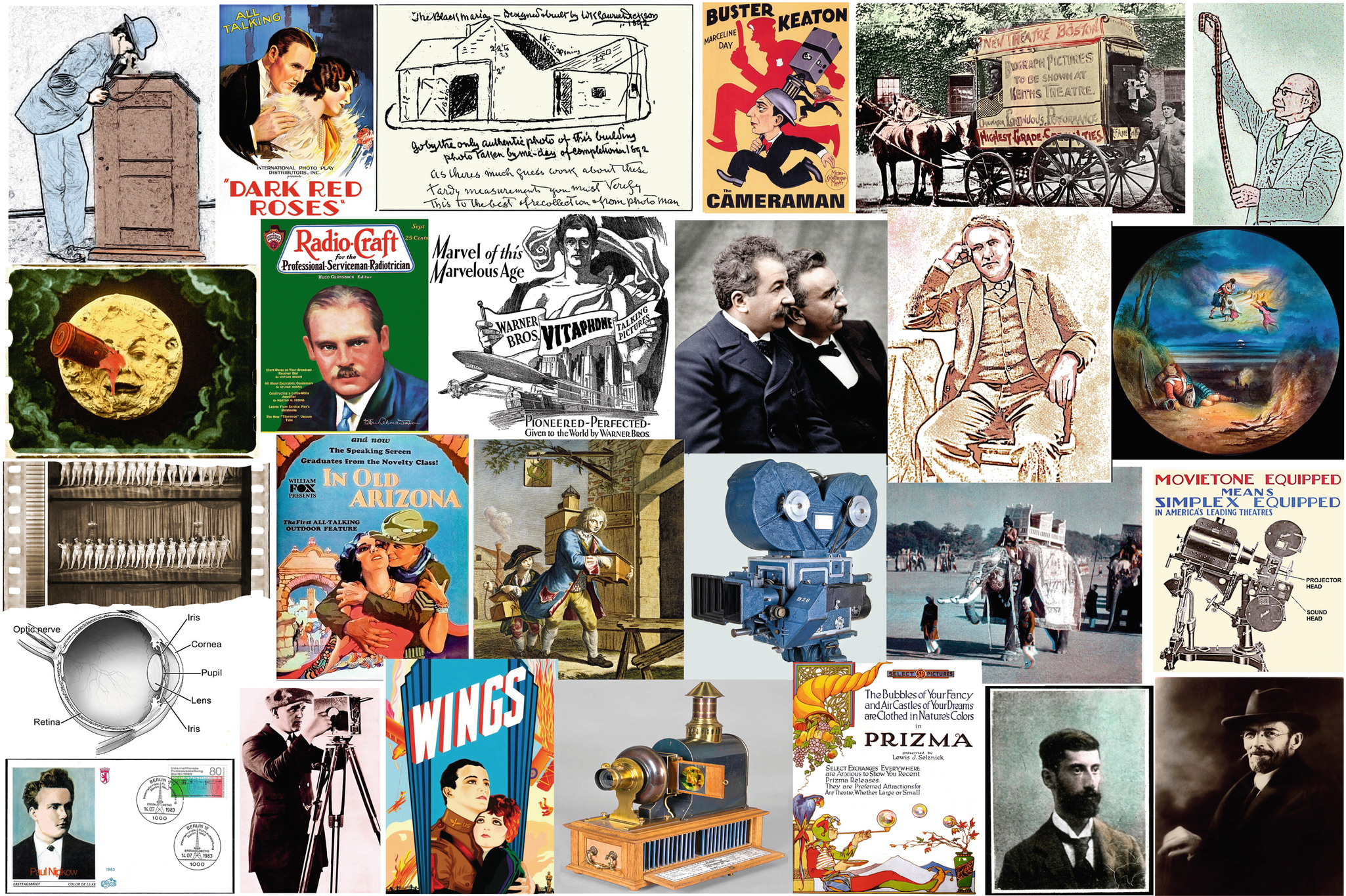

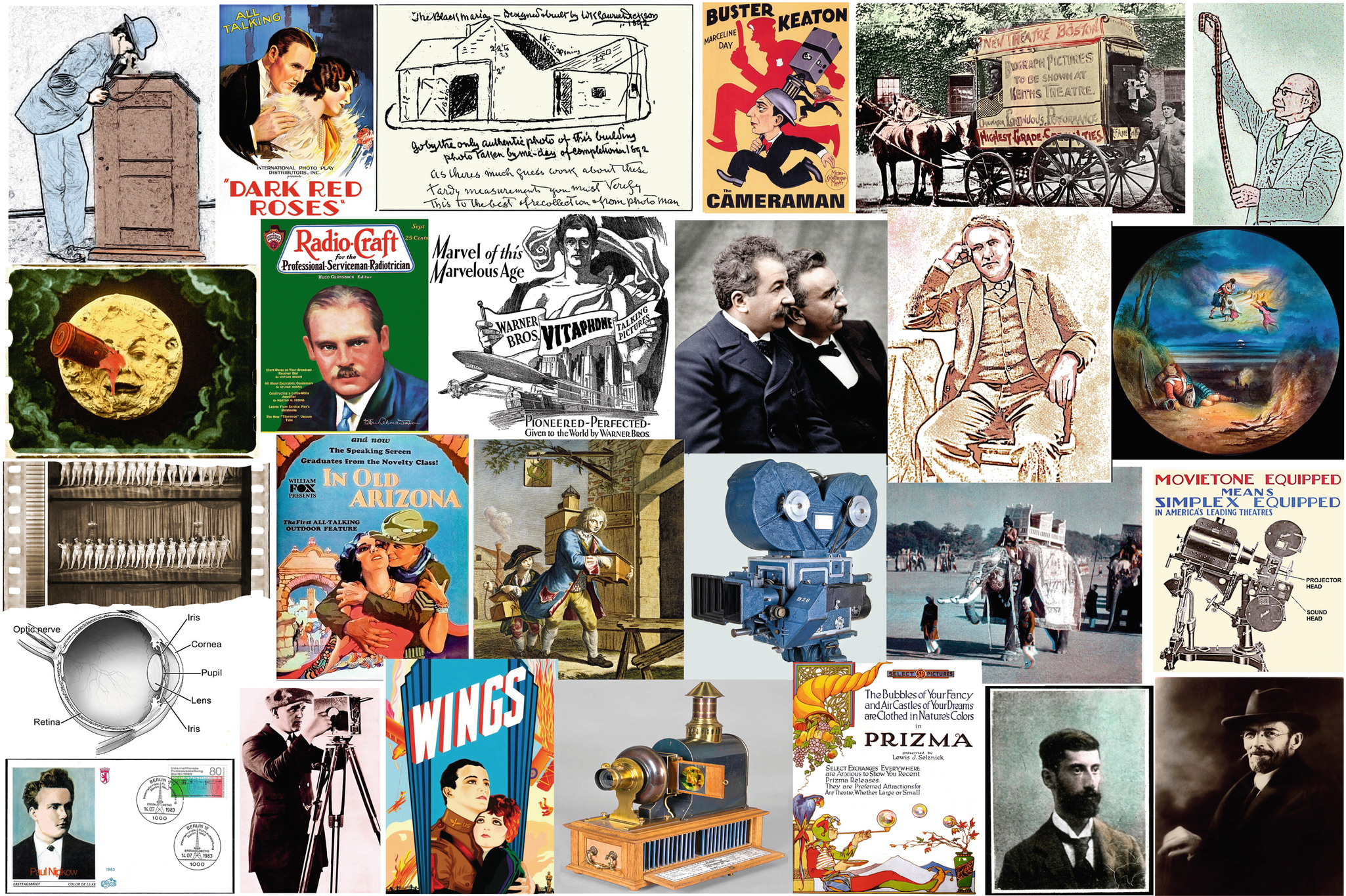

The Cinema in Flux

The Evolution of Motion Picture Technology from the Magic Lantern to the Digital Era

1st ed. 2021

Logo of the publisher

Lenny Lipton

Los Angeles, CA, USA

ISBN 978-1-0716-0950-7 e-ISBN 978-1-0716-0951-4

https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-0716-0951-4

The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Science+Business Media, LLC 2021

This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and transmission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed.

The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use.

The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. The publisher remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This Springer imprint is published by the registered company Springer Science+Business Media, LLC part of Springer Nature.

The registered company address is: 1 New York Plaza, New York, NY 10004, U.S.A.

Edwin Land was an extraordinary man who did extraordinary things like hiring women at a time when industry usually did not hire them for research positions. One of the women he hired was a chemist, Vivian Walworth. She was a friend and one of the few woman inventors (the co-inventor of Polacolor) included in these pages. It is to her memory that I dedicate this book, not simply to remember a gifted woman but to acknowledge that half of the human race has been denied an opportunity to participate in a great adventure.

Foreword

The technological development of the illusion of motion that creates moving pictures is at the core of this important book. Lenny Lipton brings tremendous clarity to this idea: moving being both apparent motion as well as an emotionally moving projected picture and sound, experienced together with others in a darkened theater. The Cinema in Flux is on the trail of a vitally important nexus between the illusion of motion and the story contained within that illusion. As cinema has improved itself over the years, adding sound, color, dimensionality, and now transforming itself into a digital medium, the vital core of why and how the medium has successfully persisted for such a span of time is a question that requires an answer. Will cinema survive by transforming itself into an even more high-powered juggernaut of immersive and experiential technical perfection or will it retain its ability to be dramatically moving and an emotional experience based on writing, directing, photography, acting, and editing, all in the service of illuminating the human experience while still preserving showmanship? The question before us is: will cinema lose its soul?

I have been a lifelong proponent of the giant screen movie experience and have had the fortunate and wondrous opportunity to work closely with Stanley Kubrick, Steven Spielberg, Sir Ridley Scott, Robert Wise, and others, discovering again and again that it is possible to fill the screen with epic spectacle and visual splendor. To me everything in a movie is an illusion, and the projected illusion of motion is at its core. The art form of cinema is boundless in its ability to transport audiences into unexpected realms of emotion, action, and wonder, by means of storytelling delivered by seasoned actors and actresses of all sizes, shapes, ages, and races. Sadly, our present obsession with spectacle and high concept (a simple and easily pitched story) is eclipsing the underpinnings of the medium itself and distracting us from the mysterious nature of the movie experience created only with the help of the cameras, lights, lenses, and projectors that deliver magic to the screen.

The Cinema in Flux reveals to us the history of how motion picture technology changed and progressed through its various eras; such knowledge can inform filmmakers of the heritage behind the camera and the screenpossibly shining a light on the question of whats next? Will cinema successfully retain its true and moving nature or become a theme park ride and gimmicky technology that has no heart? Lenny Lipton delivers the background we need to help make sure that our beloved art form does not go off the rails.

Douglas Trumbull

Southfield, MA

Nov. 16, 2019

Preface

This book follows what I have come to think of as the unitary vision of cinemas technological evolution, in alignment with that of a number of modern cinema scholars. But not so long ago, for most of those who have written about it, cinema begins with the inventions of Eastmans film, Edisons camera, and the Lumires Cinmatographe, notions that have contributed to the popular view of the subject. This impression is conveyed by dutifully noting that the magic lantern is a preamble to the big event, relegated to the archeological nether regions of pre-cinema, which include prehistoric cave paintings along with nods to Chinese, Indian, and Javanese shadow puppet shows. One can reasonably argue that their inclusion is a didactic tactic or definitional, coming down to the meaning of the word cinema. The words we use influence how we think and I therefore contend that creating this demarcation obscures a more constructive way of understanding the continuity of cinemas evolution. The idea that the era of the magic lantern is not pre-cinema but cinema itself, and not some archaic backwater, is based on the most fundamental definition of cinema technology, which in my view is the projection of motion. In an essay, Huhtamo (2011) explains that the furtherance of the acceptance of the unitary view by some modern scholars may have been inspired by the 19956 exhibition mounted by the Cinmathque Franaise Scientific Director and Curator, Laurent Mannoni, whose Trois sicles de cinma de la lanterne magique au Cinematographe was similar to one of the same titles I saw at the Cinmathque Christmas week 2009.

Huhtamo writes: Since then (the 1995-6 exhibition), there has been a flurry of books and articles that havequestioned and gone beyond prevailing ideas about moving imagesThe emerging picture is different from the one routinely found in cinema histories of just a few decades ago. The developments that preceded the appearance of the Kinetoscope and the Cinmatographe used to be lumped together under the title pre-cinema and briefly presented as a succession of steps leading to the climax: the classical cinema, epitomized by narrative feature film, movie palaces, the star cult, and the Hollywood dream factory. The work of scholars like Mannoni (2000, 2009), Huhtamo (2011), and Rossell (1998), supports the position that cinema began with the magic lantern, to which can be added the voices of Tom Gunning and the editors of