Contents

List of figures

Guide

for Jane

The building is truly a living man. You will see that it must eat in order to live, exactly as it is with man. It sickens and dies or sometimes is cured of its sickness by a good doctor. Sometimes, like man, it becomes ill again because it neglected its health. Through corruption, the body of the building rots like that of man. Through excess it is ruined and dies like man.

Filarete, Treatise on Architecture, 1464

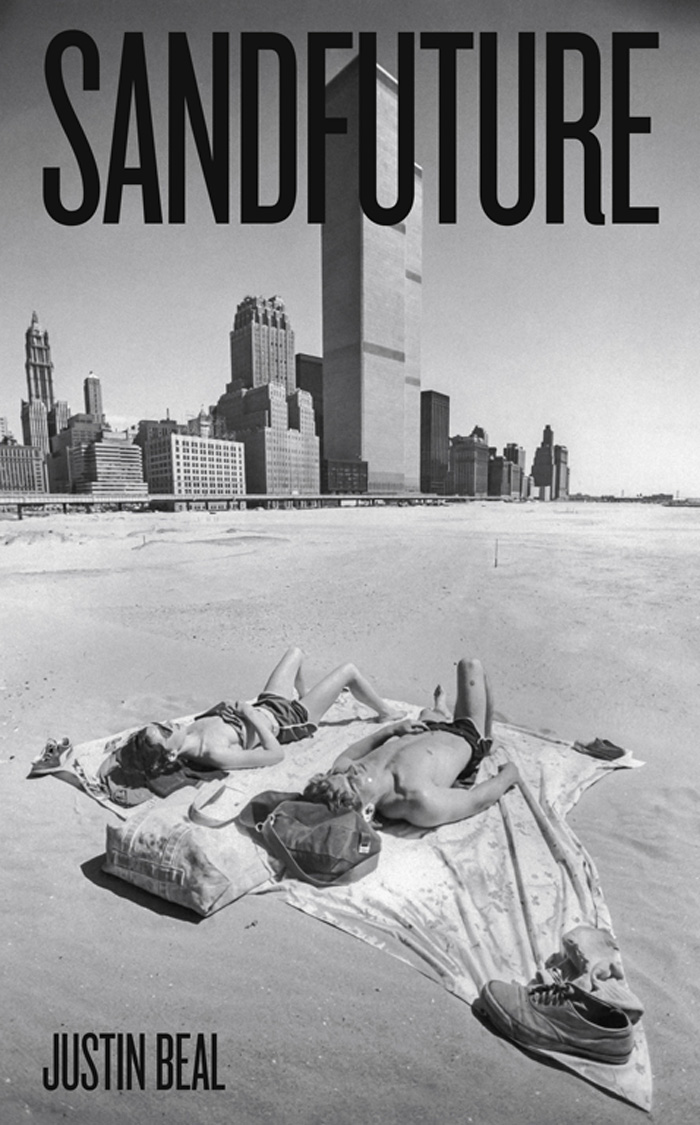

At night, alone in the plaza, you could lean your body against the chamfered corners of the aluminum facade, roll your head back and look straight up the side of the building. It was like lying on your back in the middle of an aluminum road. It was vast and, in that vastness, more closely resembled a naturally occurring phenomenon than something man-made. And there were two of them. You could stand in the space between them, where the air vibrated with silent energy, and imagine you were standing between the tines of a tuning fork. Clouds would catch on the upper floors as they passed over the city, subtly altering the weather. They were alpinea pair of aluminum mountains. They induced vertigo. They exceeded haptic experience. They failed as buildings, but they were brilliant as objects.

Water climbs up onto the narrow swath of park on the Hudson River's east embankment, washing across the four southbound lanes of the Westside Highway, around the landscaped medians and over the northbound lanes before pooling among the trashcans and hydrants on the corner of Twenty-Seventh Street. From there, the tide flows east in the grooves between cobblestones, carried first by capillary action, then forced from behind by the surge. The surface of the road disappears as the water gradually rises to the level of the concrete curb. It is late in the evening of October 29, 2012. Some water is diverted into manholes and storm drains, but not fast enough to keep pace with the rising tide as the surge pushes massive amounts of seawater up into the South Bay. The current between curbs becomes steadily stronger. The street turns into a wide flat stream. Gradually the water breaches the curbs and flows onto the sidewalk. Water backs up against thresholds and weather-stripping and sandbags, finding its way through gaps, into buildings where it crosses polished concrete floors, seeps between floorboards, pools in electrical outlets, and bloats the papered edge of sheetrock walls. Once inside the building, the water seeks its own level, finding new spaces to fill, descending staircases, and cascading through trapdoors into the cellars below. The basement spaces are not watertight. Circulation vents, air returns, and unsealed ceiling plenums allow airand now waterto flow freely between underground rooms. In HVAC parlance, these spaces are in communicationas water fills one section of the basement, it fills them all. Every door to the street is the source of a small tributary that runs into a cavernous cellaran underground swimming pool the size of a city block.

Approximately two thousand square feet of this basement was under lease, along with the corresponding groundfloor space directly above, to a small art gallery owned by Nina and her business partner Danielle. Accessed through a large trapdoor in the floor of the gallery's viewing room, their underground space held all the back-of-house fittings typical of the tradepegboards with spirit levels, spackling knives, tape measures, rolls of low-adhesive masking tape, hex keys, white cotton gloves, and utility knives hanging in neatly organized rows, gray steel shelves stacked with digital projectors and media players with international adapters, large rolls of acid-free glassine, customs forms, ammonia-free Plexiglas cleaner, a tube of mascara, a box of tampons, a lint roller, aluminum Z-clips, brass D-rings, foam blocks, an expired Oyster card, boxes of dead-stock artist publications, and stickers printed with empty or fragile or do not open with knife in thick bold capitals. There were prints stored in steel flat files and paintings in stacked plywood crates with stenciled graphics or filed neatly in carpeted storage racks, each with labels explaining details of provenance. The insurance company had suggested that all work be lifted no less than eighteen inches above the basement floor in anticipation of a possible unprecedented weather event. In an abundance of caution, Nina and Danielle had doubled the figure and secured all the work at least three feet above the floor.

I had just moved back to New York from Los Angeles to live with Nina and I had spent the days leading up to the storm unpacking books and trying to find room to hang shirts in her apartment's crowded closets. As the night wore on, the water level in the basement quickly passed eighteen inches, then thirty-six, then seventy-two. It lifted the solid wood stair to the basement upward, uncoupling it from its hardware and setting it adrift. When water rushed between the drawers of the flat file, air pockets trapped at the back of the metal cabinet forced the massive file off the ground completely, causing drawers to slide open and release their contents into the encroaching tide. Later, when the surge receded, these cabinets would look as though they had been dropped from two storiesdrawers buckled under their own weight in a heap more than twenty feet southwest of where they had begun. When the water flowing through the trapdoor into the basement had nowhere else to go, it backed up on the first floor, submerging the bottoms of office chairs, filing cabinets, bookshelves, and power strips. By this point it was a brackish mixture of salt, sewage, dirt, motor oil, and trash rinsed from the street and the cavernous basement spaces no one had seen, much less cleaned, in decades. The tide continued to rise, pushing a grimy high-water mark on the storefronts to sixteen inches above street level. It would reach as high as fifty inches elsewhere in the neighborhood.

Seven days earlier, on October 22, in the western Caribbean Sea, a low-pressure system turned into a tropical depression, gaining energy as it moved northward. By nightfall it had developed into a tropical storm. Six hours later, near the Greater Antilles, tropical storm Sandy became a hurricane before making landfall near Kingston. By Thursday the storm had crossed Jamaica, rapidly gaining strength. Sandy was upgraded to a Category 3 hurricane before hitting Santiago de Cuba hard and causing extensive damage. Cuba slowed the storm to Category 1 as it passed through the Bahamas, but early in the morning of October 29, a ridge of high pressure over Greenland caused a negative North Atlantic Oscillation that forced Sandy to take a hard left turn and accelerate again before it hit the eastern seaboard just northeast of Atlantic City. With an official designation of post-tropical cyclone with hurricane-force winds, it was not particularly powerful, but Sandy had a massive circumference, one of the largest wind fields ever recorded.

The high-pressure system surrounding the storm created a depression on the ocean surface that forced the water level higher in the relatively low-pressure eye of the storm. The elevated mass of water pushed toward the shore like a plow. Several hours later, as the plow made landfall, the east coast of New Jersey and the south shore of Long Island acted like two sides of a funnel that directed the swell up under the Verrazzano Bridge to the Upper Bay of New York Harbor and into the East and Hudson rivers, rolling over the low-lying landfill of Battery Park City at the southern tip of Manhattan. As it moved inland, the water inundated Breezy Point and the Rockaways, Coney Island, parts of Staten Island, and Manhattan's Lower East Side, flooding streets, tunnels, and subway lines. With nowhere left to go, the surge pushed up the Hudson, gathering where the river narrows as it turns slightly eastward at the island's elbow just above Twenty-Third Street, backing up into Hoboken and spilling over into the low-lying portion of Chelsea, flooding its piers and a dozen acres of Manhattan's West Side.