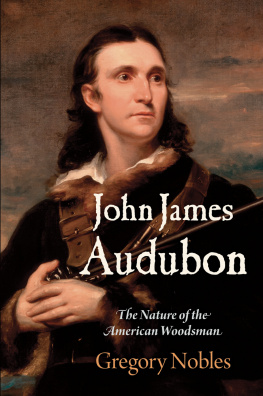

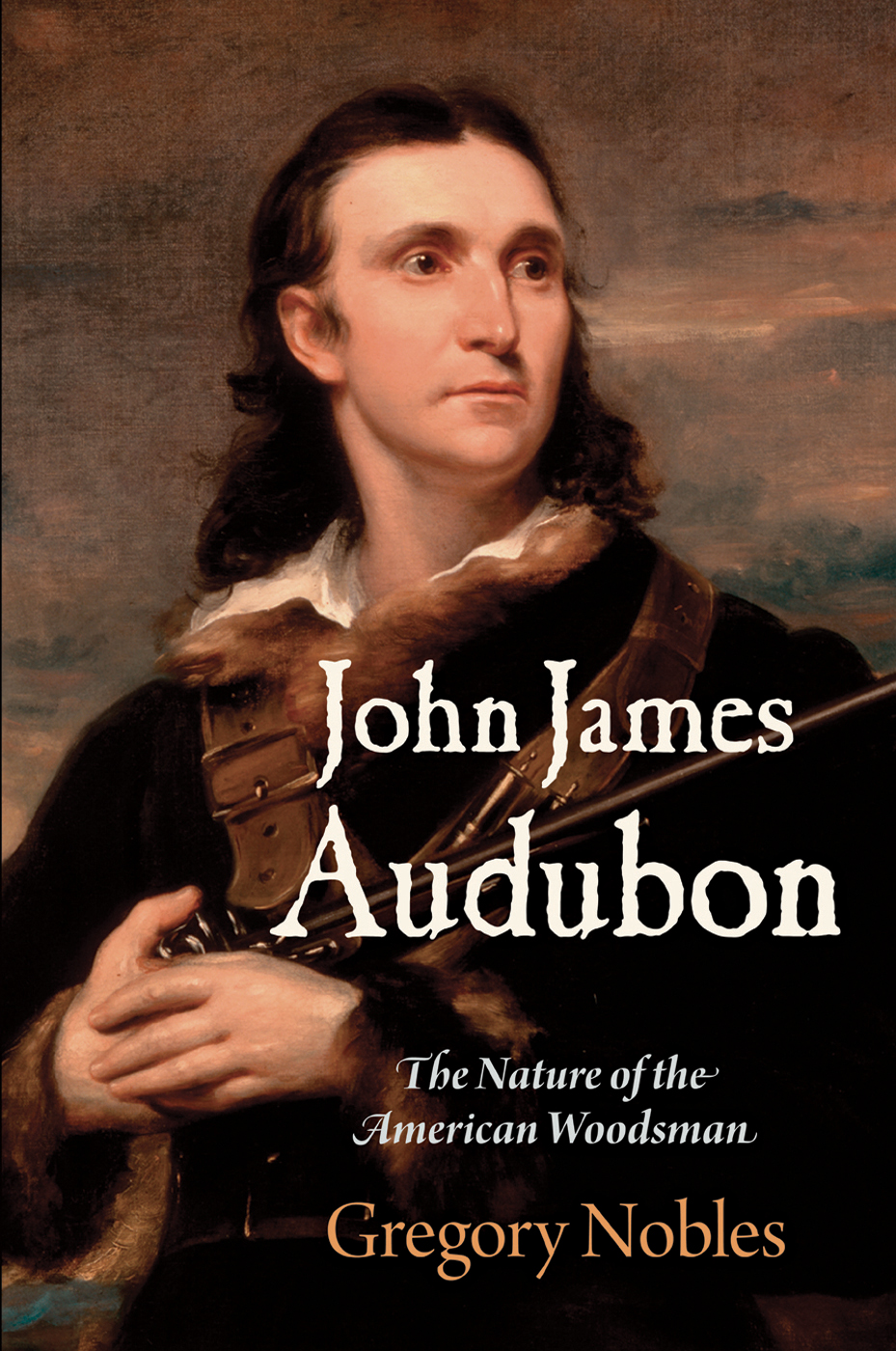

John James

Audubon

EARLY AMERICAN STUDIES

Series editors:

Daniel K. Richter, Kathleen M. Brown, Max Cavitch, and David Waldstreicher

Exploring neglected aspects of our colonial, revolutionary, and early national history and culture, Early American Studies reinterprets familiar themes and events in fresh ways. Interdisciplinary in character, and with a special emphasis on the period from about 1600 to 1850, the series is published in partnership with the McNeil Center for Early American Studies.

A complete list of books in the series is available from the publisher.

John James

Audubon

The Nature of the American Woodsman

Gregory Nobles

UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS

PHILADELPHIA

Copyright 2017 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nobles, Gregory H., author.

Title: John James Audubon : the nature of the American woodsman / Gregory Nobles.

Other titles: Early American studies.

Description: 1st edition. | Philadelphia : University of Pennsylvania Press, [2017] | Series: Early American studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016046873 | ISBN 9780812248944 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Audubon, John James, 17851851. | NaturalistsUnited StatesBiography.

Classification: LCC QL31.A9 N63 2017 | DDC 508.092 [B] dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016046873

To Phil Terrie,

good writer, good birder, good friend

Contents

John James

Audubon

Introduction

Creating Art, Science, and Self

Kind Reader,Should you derive from the perusal of the following pages a portion of the pleasure which I have felt in collecting the materials for their composition, my gratitude will be ample, and the compensation for all my labours will be more than, perhaps, I have a right to expect from an individual to whom I am as yet unknown.

John James Audubon, Introductory Address, in Ornithological Biography

If anyone had been offering the nineteenth-century version of a MacArthur genius grant, John James Audubon should have had one. To the extent that genius stems from abundant quantities of imagination, talent, and tenacity, Audubon repeatedly demonstrated all three. He dedicated almost his entire adult life to a remarkably challenging, maybe crazy-seeming commitment to depict, in both paint and print, every bird that flew over and within the United States. He succeeded in that task as no one had done before, and he did so at a great personal sacrifice, with almost no external support. He certainly could have used the MacArthur money.

Today, the main source of Audubons enduring claim to genius remains the remarkable visual record he left as an artist. His major workhis Great Work, as he liked to call itwas the famous collection of avian art, The Birds of America, which came out in a process of piecemeal publication between 1827 and 1838.surpassing earlier sales of the Gutenberg Bible ($5,390,000 in 1987) and Chaucers Canterbury Tales ($7,565,396 in 1998) to set a world record amount for a printed book of any sort. Ten years later, in 2010, the price rose even higher, and a complete set of The Birds of America fetched $11.5 million.

But whatever its record-setting size and price, The Birds of America does not stand alone as the sole measure of Audubons significance. His bird images are only the most visibleand now, of course, the most valuableaspects of his larger project. In addition to being a skilled painter, he was also a remarkably prolific writer. Audubon wrote consistently, almost incessantly, throughout his adult years, and his outpouring of words, both published and personal, is especially impressive. He confessed at one point that he thought himself far better fitted to study and delineate in the forests than to arrange phrases with sensible grammarian skill, but his skill with the pen ranks just a bit behind his mastery with the brush. His major published work, the five-volume, three-thousand-page Ornithological Biography (18311839), came out as a companion piece to The Birds of America, and taken together, the two works make an innovative and interactive reading/viewing experience. In the time of Audubons life, in fact, when newspapers and other publications reproduced any number of chapters and extracts from his writings, probably as many people read Audubons words as saw his birds.

We still need to pay attention to his writing. In addition to producing the massive Ornithological Biography, Audubon filled thousands more pages as a prodigious journal keeper and letter writer, and those more personal documents provide an immense source of insight into the complicated persona emerging from behind the more famous paintings. Many of those personal writings may not have been so personal after all. He seldom seemed to be writing for himself alone, in the self-reflective, therapeutic sense that many people keep journals today, but always with the notion that someone else would be readinghis wife, his sons, perhaps some broader audience, but certainly someone.

Audubons sense of audience became more immediately evident in Ornithological Biography, in which he repeatedly wrote directly to his Kind Readera phrase that he used in some variation well over three hundred timesreaching out to embrace the reader as a fellow student of nature, sometimes even as a fictive companion in the search for birds.sought the elevated status of a man of science in the early republic. By looking at Audubons art and science, his painting and writing, his elite and popular audiences, we can situate his achievements in the larger cultural context of the new nation.

That larger context became a critical element of Audubons relationship with the reader. His writings went well beyond birds, well beyond scientific description. In the first volume of Ornithological Biography, he generously offered to take his reader out of the mazes of descriptive ornithology by presenting you with occasional descriptions of the scenery and manners of this land. He stuck to his obligations to birds well enough, but, still, Ornithological Biography contains so many passages about Audubon himself that it could well be called Ornithologists Autobiography.

In whatever form, in fact, whether his published works or personal journals, Audubon almost always wrote about his life, and he was almost always writing a Life, crafting various parts of the Audubon story that would both shape and reinforce the role he would so brashly embrace. Reading Audubon gives us by far the best way to see the way he created an always expressive, sometimes audacious, and certainly self-conscious sense of himself as an artist, as a scientist, and, above all, as a larger-than-life, self-fashioned symbol, the American Woodsman.

Next page