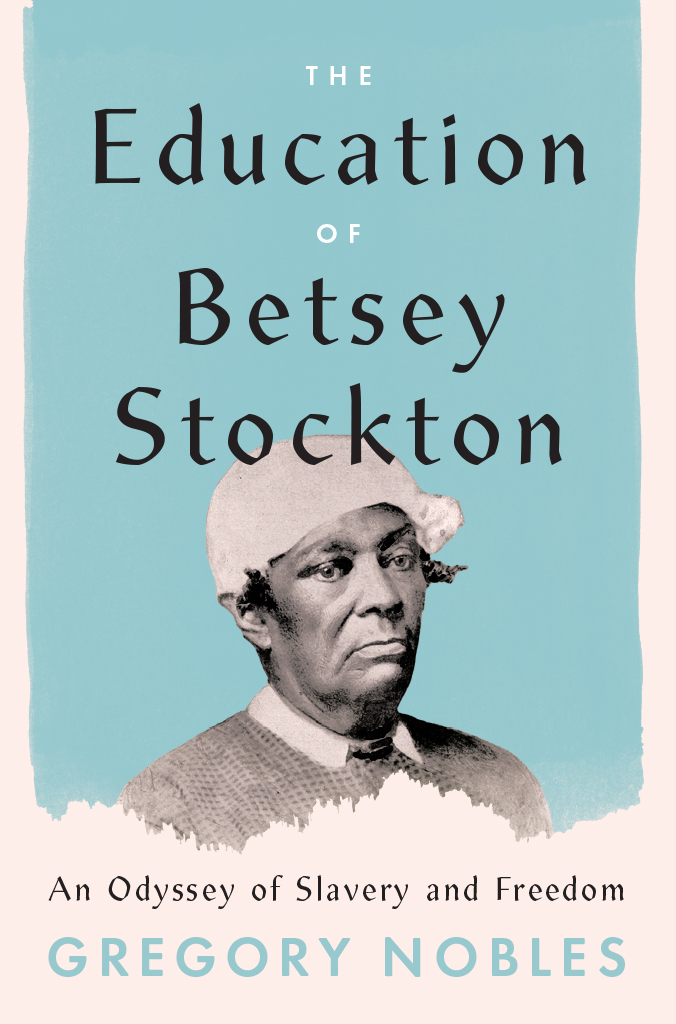

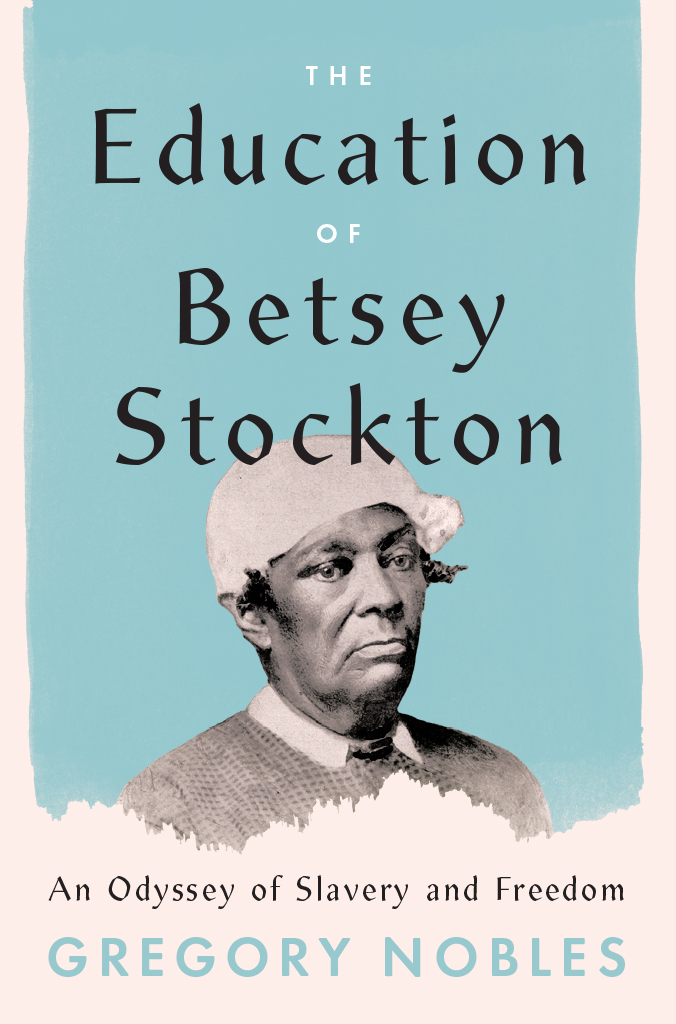

The Education of Betsey Stockton

The Education of Betsey Stockton

An Odyssey of Slavery and Freedom

Gregory Nobles

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2022 by Gregory Nobles

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69772-7 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-69786-4 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226697864.001.0001

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nobles, Gregory H., author.

Title: The education of Betsey Stockton : an odyssey of slavery and freedom / Gregory Nobles.

Description: Chicago : The University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021040707 | ISBN 9780226697727 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226697864 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Stockton, Betsey, 1798?1865. | African American womenNew JerseyPrincetonBiography. | SlavesUnited StatesBiography. | FreedmenUnited StatesBiography. | Women missionariesUnited StatesBiography. | MissionariesUnited StatesBiography. | MissionariesHawaiiBiography. | Women teachersUnited StatesBiography. | PresbyteriansBiography. | Princeton (N.J.)Biography. | LCGFT: Biographies.

Classification: LCC E185.97.S86 N63 2022 | DDC 974.9/65 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021040707

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Anne

Contents

Betsey Stockton had made up her mind to get out of Princeton and never come back. She would be leaving everyone and everything she had known, including the institution of slavery, into which she had been born. Now in her early twenties and a free woman, she would be making the biggest step in her life so fargoing to the Sandwich Islands as a missionary. She would be the first single woman, the first Black woman, to do that; she would be making history.

But she had to make one last stopto say good-bye to the Reverend Ashbel Green, a man with whom she had had a long and complicated relationship. As an enslaved child, she had been given to Greens wife, and she had grown up under Greens authority, first in slavery and then in indentured servitude, until her teenaged years, when she became emancipated. Even then, she stayed in his household, working for wages, saving her money until she had enough to leave. This would be an emotional farewell.

That evening, she stood in the downstairs hallway in Greens house, outside his study, waiting for him to usher her in. Like Green, she had come to live in that house in October 1812, when he became president of the College of New Jersey. She had cooked and cleaned and done all sorts of chores, and when she could find time, she immersed herself in the books in Greens study. Betsey Stockton had never been to school, but she had become an eager reader, even of the ponderous volumes that lined Greens shelves. When she came into his study now, she was at home.

She didnt come alone. Joining her was a thin, sharp-featured young man about her age named Charles Samuel Stewart, who had been one of Greens students at the college and later had graduated from the nearby Princeton Theological Seminary. Stewart was white, Stockton was Black, and they had determined to work together as part of a larger missionary familyincluding Stewarts young bride Harriet and fifteen othersheading for the Pacific under the auspices of the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (ABCFM).

When Betsey Stockton had applied to the ABCFM a year earlier, Ashbel Green wrote a letter of recommendation that covered, to use Greens terms, her life from the time she was given, as a slave to Greens wife, through her wild and thoughtless early teenage years, and coming to her saving change of heart a little later. Now, she was about to start the next chapter of her life, leaving for New Haven to board a whale ship, sailing to the Pacific with her own sense of purpose.

By contrast, Ashbel Green was old, just past his sixtieth birthday, white-haired and tired, worn down by the decade of his college presidency. In that time he had suffered the deaths of two wives and one son, he had been derided and defied by unruly students, and he had lost the favor of the college trustees. He was in fact about to resign, leaving Princeton himself, for Philadelphia.

Betsey Stockton and Charles Stewart and Ashbel Green talked, prayed, and finally took leave of each other. The next day they went East and I West, Green would write in his diary, probably to meet no more on earth.

But they would meet again, and in time, Betsey Stockton would return to Princeton. She would become a leader in the towns Black community, a woman who helped build institutions of resistance to racism over the decades until she died, in 1865, the year slavery came to a legal end in the United States.

Searching for Betsey Stockton

Today, its still possible to find markers honoring Betsey Stockton in Princeton, some old, some very new. The newest is a plaque that stands in front of the old Presidents House (now called Maclean House, home of the universitys Alumni Association), which lists her as one of at least sixteen enslaved people who lived there in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. But to see the olderand more personalmemorials to her, you have to leave the campus, cross Nassau Street, the towns main thoroughfare, then head down Witherspoon Street, the center of the towns small business district. The shopping area fades away after only two blocks, at the Paul Robeson Center for the Arts, named for the famous actor, athlete, and activist, who was born in Princeton. A block or so more takes you to the towns old cemetery on the right side of the street and the historic Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church on the left, a modest white frame church building. Its just a few blocks from the campusbut in a historically different world.

Outside the church is a sign, part of the New Jersey Womens Heritage Trail. Betsey Stockton (17981865) began life as a slave for the prominent Stockton family in Princeton, it reads, going on to give the basic outline of her lifebecoming free, going to Hawaii as a missionary, coming back to teach in Philadelphia and Canada, then returning to Princeton in 1835. There she spent the rest of her life working to enrich the lives of members of her local community, as one of the founding members of the First Presbyterian Church of Colour and teaching in the Witherspoon School for Colored Children. When Betsey Stockton died in Princeton at the age of 67, the sign concludes, she was memorialized by former students who donated a stained glass window in her honor to the church.

And inside the church theres the window, an orderly ensemble of geometric shapes in reds, blues, purples, and yellows, that contains only seven words: Presented by the Scholars of Elizabeth Stockton. Theres also a brass plaque, installed in 1906 on the same wall as the window, that notes her long life of service in Princeton, where she became a powerful influence for good in the community. Since then, she has lived in the collective memory of the towns Black community, particularly in the Witherspoon Street Presbyterian Church, and in the recent work of the Witherspoon-Jackson Historical and Cultural Society to tell the larger history of African American people in Princeton.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).