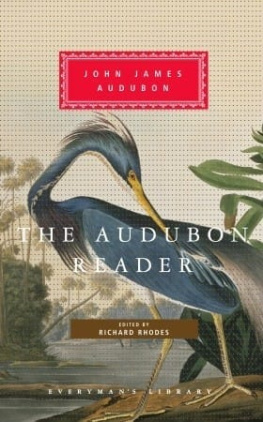

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

First included in Everymans Library, 2006

Copyright 2006 by Richard Rhodes

Typography by Peter B. Willberg

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Distributed by Random House, Inc., New York. Published in the United Kingdom by Everymans Library, Northburgh House, 10 Northburgh Street, London EC1V 0AT, and distributed by Random House (UK) Ltd.

US website: www.randomhouse/everymans

ISBN: 1-4000-4369-7 (US)

1-85715-284-0 (UK)

eBook ISBN: 978-0-375-71270-8

A CIP catalogue reference for this book is available from the British Library

v3.1

For Bill Steiner

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction: Americas Rare Bird

The handsome, excitable eighteen-year-old Frenchman who would become John James Audubon had already lived his way through two names when he landed in New York from Nantes in August 1803. His father Jean, a canny ships captain with Pennsylvania property, had sent his only son off to America with a false passport to escape Napoleonic conscription, the young mans second or third escape. The tenant who farmed the plantation Jean Audubon owned, Mill Grove, which straddled Perkiomen Creek close above Valley Forge, had reported a vein of lead ore. John James or Jean Jacques or Fougre was supposed to evaluate the tenants report, learn what he could of plantation management and eventuallysince the French and Haitian revolutions had all but erased the Audubon fortunemake a life for himself.

He did that and much, much more. He married an extraordinary woman, opened a string of general stores on the Kentucky frontier, built a great steam mill on the Ohio River, explored the American wilderness from Galveston Bay to Newfoundland, hunted with Shawnees and Osages, rafted the Ohio and the Mississippi, identified, studied and drew almost five hundred species of American birds, saw English noblemen kneel before him to examine his dazzling drawings, raised the equivalent of several million dollars to publish a great work of art, wrote five volumes of bird biographies larded with narratives of pioneer life, won fame enough to dine with presidents and became a national icon, The American Woodsman, his ultimate appellation, a name he gave himself.

John James had first been Jean Rabin, his fathers bastard child, born in 1785 on Jean Audubons sugar plantation on Saint Domingue (soon to be renamed Haiti) to a twenty-seven-year-old French chambermaid, Jeanne Rabin, who died of infection within months of his birth. The first stirrings of slave rebellion in 1791 prompted Jean Audubon to sell what he could of his holdings and ship his son home to France, where his wife Anne, a generous older widow whom Jean had married long before, welcomed the handsome boy and raised him as her own.

When the Terror approached Nantes in 1793 the Audubons had formally adopted the bastard Jean Rabin, christening him Jean Jacques or Fougre Audubon, FougreFernan offering to placate the Revolutionary authorities, who scorned the names of saints. Jean-Baptiste Carrier, sent out from Paris to quell the Vendan peasant counterrevolution, ordered the slaughter of thousands in Nantesa guillotine and firing squads in the town square, victims chained to barges sunk in the Loire, tainting the river for monthsand even though Jean Audubon was an officer in the Revolutionary French navy, he and his family were jailed and barely spared. Two escapes and two names, and now a third escape and John James; but this escape opened up a world.

The young country to which John James Audubon emigrated in the summer of 1803 was barely settled beyond its eastern shores; Lewis and Clark were just then preparing to depart for the West. France in that era counted a population of more than 27 million, Britain about 15 million, but only 6 million people yet thinly populated the United States, two-thirds of them living within fifty miles of Atlantic tidewater. In European eyes America was still an experiment. It would need a second American revolutionthe War of 1812to compel England and Europe to honor American sovereignty.

But the first generation of Americans which the young French migr was joining was different from its parents. Like Audubon, it had left home to migrate westward. Like Audubon also, it would break with tradition and take great risks in pursuit of new opportunities which its elders had not enjoyed. National spirit is the natural result of national existence, Gouverneur Morris had predicted back in 1784; and although some of the present generation may feel colonial oppositions of opinion, that generation will die away, and give place to a race of Americans. Audubons was the era, as the historian Joyce Appleby has discerned, when the autonomous individual emerged as an ideal. American individualism was not a natural phenomenon, Appleby writes; it [took] shape historically [and] came to personify the nation and the free society it embodied. And no life was at once more unique and more representative of that expansive era when a national character emerged than Audubons. Celebrate him for his wonderful birds; but recognize him as well as a characteristic American of the first generationa man who literally made a name for himself.

Lucy Bakewell, the tall, slim, gray-eyed girl next door whom he married, came from a distinguished English family. Erasmus Darwin had dandled her on his knee in their native Derbyshire. Her father had moved his family to America to follow Joseph Priestley, the chemist and religious reformer, but opportunity had also drawn the Bakewells. Their plantation, Fatland Ford, was more ample than the Audubons, and William Bakewell sponsored one of the first experiments in steam-powered threshing there while his young French neighbor lay ill with a fever in his house under his talented daughters care. Lucy was a gifted pianist, an enthusiastic reader, a skillful ridersidesaddlewho kept an elegant house. She and John James, once they married and moved out to Kentucky in 1808, regularly swam across and back the half-mile-wide Ohio for morning exercise.

Lucys handsome young Frenchman had learned to be a naturalist from his father and his fathers medical friends, exploring the forested marshes along the Loire. Her younger brother Will left a memorable catalog of his future brother-in-laws interests and virtues; even as a young man, Audubon was someone men and women alike wanted to be around:

On entering his room, I was astonished and delighted to find that it was turned into a museum. The walls were festooned with all kinds of birds eggs, carefully blown out and strung on a thread. The chimney-piece was covered with stuffed squirrels, raccoons, and opossums; and the shelves around were likewise crowded with specimens, among which were fishes, frogs, snakes, lizards, and other reptiles. Besides these stuffed varieties, many paintings were arrayed on the walls, chiefly of birds. He had great skill in stuffing and preserving animals of all sorts. He had also a trick in training dogs with great perfection, of which art his famous dog Zephyr was a wonderful example. He was an admirable marksman, an expert swimmer, a clever rider, possessed of great activity [and] prodigious strength, and was notable for the elegance of his figure and the beauty of his features, and he aided nature by a careful attendance to his dress. Besides other accomplishments he was a musician, a good fencer, danced well, and had some acquaintance with legerdemain tricks, worked in hair, and could plait willow baskets.