About the author

Jack Marx was born in Maitland in 1965. A freelance journalist and author of two books, Jack has been writing for newspapers and magazines both in Australia and abroad since 1992. He is the recipient of the 2006 Walkley Award for Newspaper Feature Writing, which he received for I Was Russell Crowes Stooge, his online account of the unfolding relationship between himself and the Hollywood Oscar winner. He lives in Broken Hill.

Also by Jack Marx

Also by Jack Marx

Sorry the Wretched Tale of Little Stevie Wright

The Damage Done Twelve Years of Hell in a Bangkok Prison

(with Warren Fellows)

Title page

Australian Tragic

Jack Marx

Copyright page

First published in Australia and New Zealand in 2009

by Hachette Australia

(An imprint of Hachette Australia Pty Limited)

Level 17, 207 Kent Street, Sydney NSW 2000

www.hachette.com.au

This edition published in 2015

Copyright Jack Marx 2009, 2015

This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the

purposes of private study, research, criticism or review permitted

under the Copyright Act 1968 , no part may be stored or

reproduced by any process without prior written permission.

Enquiries should be made to the publisher.

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication data is available from the National Library of Australia

978 0 7336 2341 7 (pbk.)

978 0 7336 2608 1 (ebook edition)

Tales Australia.

Australia History.

994

Cover illustration and design by Saso Content & Design Pty Ltd

Author photo courtesy of Simon Obarzanek and Karen Woodbury Gallery, Melbourne

Text design by Saso Content & Design Pty Ltd and Bookhouse, Sydney

eBook by Bookhouse, Sydney

Dedication

This book is dedicated with thanks to

Matt Richell

Introduction

Introduction

Introduction

On a winters evening in Melbourne in 1880, during the opening night of Les Huguenots at the old Opera House in Bourke Street, a man named Greer stormed the dress circle during the climactic third act, a pistol in his hand. What happened next and how the public reacted to it is a good illustration of the moral values that shepherded Australian society of old, and its a shame that the keepers of colonial record regarded such episodes as embarrassments rather than as events of historical interest. No doubt there are thousands of similar tales buried in the same dungeon where I found this one: in the pages of old newspapers, readily accessible through our libraries, but forgotten where the national history is concerned. Thats a pity.

Anyone who has ever snored through lessons at an Australian school knows that the official history of our nation is as boring as milk. Where American kids get to thrill to tales from the War of Independence, the Civil War, the various bloody encounters of the Wild West and enough assassinations to keep conspiracy theorists busy for a century yet, our poor little bastards are forced to dream up ingenious ways to stay awake during lectures on the Gold Rush, Federation, and the adventures of Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth. Gallipoli, the military tragedy trumpeted as being the birth of our nation, was undoubtedly one of the most tedious battles in the history of armed conflict, and our most intriguing politician by a long way is only interesting for the fact that he went missing while in office (but that more of them would).

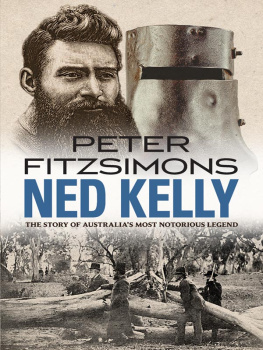

This is the history that has been chosen for us to read, cherry-picked by custodians of the lucky country myth, a pantomime in which Australia is forever cast as a kingdom of eternal heroism and good, our coastline corralling a population of humble champions, selfless entertainers and assorted larrikins with hearts of gold. In our history books, even a violent bullshit artist like Ned Kelly is varnished with a gallant sheen, so as to make the mongrel a quaint matching bookend for such inoffensive figurines as Bradman, Darcy and Dame Nellie Melba.

When not concerned with the follies, Australias history, as packaged by bureaucrats in successions of education departments, is perhaps unsurprisingly obsessed with authority and victory; those in charge, those who got there first, and those who obeyed their superiors. Thus we are forced to fossick for something interesting in the lives of such pets of the establishment as James Cook, Arthur Phillip, Lachlan Macquarie, Charles Sturt, John Oxley politicians and surveyors, basically. Such people are important joists in the historical scaffold, but to fixate upon them alone is like going to the football and cheering for the umpires, the security staff and the club secretaries up in the corporate box. Anyone who is honest with themselves knows that the really interesting stuff is happening not in the realm of officialdom, but in the field of play, or sometimes in the stands where the players dont always come with famous names or precious reputations.

Jim Hall, for example, was a Sydney-born boxer who, in a short but explosive nineteenth century career, knocked out more opponents than Les Darcy ever would, and whose fight with world champion Bob Fitzsimmons in New Orleans in 1893 was billed as the Fight of the Century, its purse of $40 000 being the largest the American ring had ever seen. There are no books about Jim Hall, no entry for him in the Australian Dictionary of Biography , no mention of his name in our sporting halls of fame. The reason you havent heard of Jim Hall is because he was a bastard, a shocking drinker who fought whether he was in the ring or not, some of his most noteworthy brawls including drunken rages against friends, trainers and doctors. Unlike Darcy, Jim Hall was not the type of role model our educators like to push on Australian kids.

But historys not just about education. Its about storytelling, wonder, and pointless, amoral voyeurism. With the increasing digitisation of old newspaper pages, once only available on microfilm, a whole new door is being opened to those who are tired of the salt-of-the-earth blokes, passionately politicised murderers and stoic hand-to-breast heroines of Australias official history. Beyond are thousands of characters like Jim Hall and J. J. Greer, whose faces will never appear on bank notes, but whose value to the history of this country is inestimable.

Though my purpose in writing Australian Tragic was to present real stories in the sensational dime novel style of old, I have invented no people or events and I have been careful to invent no dialogue. All action comes from official documents, contemporaneous reports or eyewitness testimony, and any liberties I have taken with presumed thoughts or observations have been based, I believe, upon guesses whose sound educations can be found in the rear of this book.

Some may wonder why many of the events and characters herein deserve to be so remembered. But Australian life is built within the hours of the dead lives that are summarised in the end with a few words in the obituary column and some verse on a headstone but which were as long and nourishing, charming and boring, hurt and spiteful as our own. Perhaps they, too, thought their lives insignificant, when in fact they instruct us in death. We can, in the words of Alan Feuer, hear their whispers drifting down the hallway: Eat well, drink much, love whatever you can on that side of the pavement. These are things we know.

Jack Marx, Sydney

Moloch

Moloch

Moloch

Ancient legend speaks of Moloch, a fiery Prince of Hell who takes pleasure in the sorrow of mothers. The pagans sacrificed their young to him, in temples built in his likeness giant effigies of iron, a creature with the body of a man and the head of a bull. Fires burned in his belly, the tips of flames seen to dance in the darkness of a mouth that was open to receive the loved. Parents were forbidden to cry as their children burned to do so was an insult to Moloch, who desired his gifts be delivered by disciples willingly, joyfully, and with no regret. And so that mothers might not be moved by the anguished cries of their suffering babes, there was music and drumming, cheering, the piping of flutes and the hammering of tambourines the sounds of a carnival to lure children to their doom and hide the screams of death.

Next page