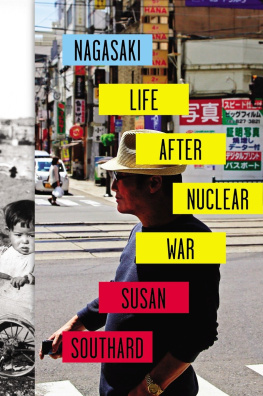

Gently to Nagasaki

Copyright 2016 Joy Kogawa

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, .

Caitlin Press Inc.

8100 Alderwood Road,

Halfmoon Bay, BC, V0N 1Y1

www.caitlin-press.com

Text and cover design by Vici Johnstone

Cover image by Mikel Martinez de Osaba, courtesy creativemarket.com

Printed in Canada

Caitlin Press Inc. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada, the Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kogawa, Joy, author

Gently to Nagasaki / Joy Kogawa.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-987915-15-0 (paperback).ISBN 978-1-987915-26-6 (ebook)

1. Kogawa, Joy.2. Kogawa, JoyChildhood and youth.3. Japanese

CanadiansEvacuation and relocation, 1942-1945.4. Japanese

CanadiansBiography.5. Authors, Canadian (English)Biography.

6. CanadaRace relations.I. Title.

PS8521.O44Z46 2016C813'.54C2016-903260-4

C2016-903261-2

Gently to Nagasaki

Joy Kogawa

Caitlin Press

the leaves of the tree were for the healing of the nations.Revelations 22:2

If I could follow the stream down and down to the hidden voice, would I come at last to the freeing word?

In the dark light before dawn, in the deep light before dawn, the hidden voice comes. Named and Nameless, the Goddess of Mercy, She, the compassionate one who heeds the wailing in a world of weeping, comes to us.

She dances the transition between moon and morning, robed in the whiteness of clouds. Down and down through the sensate sea, down through the amniotic deep she dances, a rider of the vast turtle that roams the eastern myths. We hear her in the breath surrounding this blue-green planet, her singing as sunlight in the new day rising. In the first call of the first creatures, in the orchestrators of waking we hear her.

I am with you, she sings. I am with you through the water, under the water, in the birthing, in the forgetting, in the terror and at the heart of what you most fear, I am with you. Through the long dark night of every absence, I am with you, therefore fear not.

Part One

1

The wind bloweth where it listeth, and thou hearest the sound thereof, but canst not tell whence it cometh, and whither it goethJohn 3:8

Huddled somewhere in a corner of Japan, two or three Christians of Japanese ancestry gather with a candle in a quiet place devoid of derision.

There are not many of us. Fewer than one percent of Japans citizens call themselves Christians. Yet there have been eight Christian prime ministers, which seems remarkable to me.

My grandfather, Yataro Yao, a lonely and motherless youth, was the first Christian in our family. My mother, his first child, born in 1897 at Aokusa cho, Kanazawa, Ishikawa-ken, was also a lonely, motherless child. She was the most truthful person I have known and the most earnest Christian. My father, raised a Buddhist in Japan, was converted to Christianity in Canada and became a priest in the Anglican Church.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, the government of Canada interned the entire Japanese-Canadian population along the British Columbia coast. Twenty-two thousand of us were suddenly enemy aliens, a security threat, potential fifth columnists, a breath away from barbarity. We were removed on trains to the BC interior mountains.

In Slocan, the best of the ghost towns to which we were sent, our family of four stayed for three years in a log cabin with a cow-dung ceiling at the foot of the mountains. My older brother Tim and I watched newsreels with hundreds of other kids at the Saturday night movies in the Odd Fellows Hall. We saw how unthinkably horrible the Japs were. We were not Japs, my brother said. Except that we were. Not all Germans were Nazis, but all Japanese were Japs.

The homes we had left fell en masse into the hands of the Custodian of Enemy Alien Properties for safekeeping. Eventually we learned what safekeeping meant. Safe, but not for us. Keeping, but not for us. Our properties were sold without our consent and none of us got them back. After the war we were still, as the title of Ken Adachis seminal book tells us, The Enemy That Never Was.

Having disappeared our houses, the government decided next to disappear us. Its Dispersal Policy, intended to destroy our community and to eliminate an essential belongingness at the core of our identity, worked almost perfectly. We were tossed as pearls of a broken necklace and as scraps for the dogs of labour, a few here, a few there, over the vast Canadian landscape. We Japanese were no longer we Japanese. Many of us, Canadian-born nisei, learned to say with a sense of appropriateness that most of our friends were white and we hardly knew any other Japanese Canadians. As a community, we paid the price. We were the stand-ins, the scapegoats, for the enemy, Japan.

Naomi Nakane, the narrator of my novel Obasan, experienced racism as a private grief. The idyllic days of her childhood in Vancouver within an intact family and church community were forever lost. She longed for the picnics at Kitsilano beach, the incomparable Stanley Park. With the salt smell of the sea replaced by prairie dust and the faint tang of manure, she mourned the streetcars and escalators of the city, her old life of stories, music, dolls in her familys charming house of many windows.

For the most part, what happened to the fictional family happened to mine. We fell from comfort in the city to a cabin in the mountains and ended up along with others, beet workers, in an unlivable hovel in southern Alberta. What is entirely fictional in Obasan is the disappearance of Naomis mother.

In reality, my gentle, fashionable Mama, the best mother in the world to my childs mind, never left us. But she was irrevocably altered by the harshness of her new reality. She became in truth the Obasan, the surrogate mother of Naomi, a woman of silence. One friend suggested I made two mothers out of one in my novel because I could not be reconciled to the change.

In Obasan, little Naomis greatest catastrophe is the loss of her beloved mother. Just before the war, her mother went to Japan to visit an ailing grandmother. In an early draft of the novel, her whereabouts remained a mystery throughout.

What happened to the mother? the publisher who finally accepted my manuscript asked.

I dont know. I think she vanished, I said. Isnt life like that? People disappear.

The reader has to know, Joy.

I took the puzzle back into myself. The mother was lost in a faraway country, during a faraway war. She could have been suffering from amnesia in a mountain village. She could have died in the firebombing of Tokyo. There could have been a scandal that meant she could never return. She could be anywhere. Or nowhere.