Northern Illinois University Press, DeKalb 60115

2015 by Northern Illinois University Press

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

24 23 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 1 2 3 4 5

978-0-87580-726-3 (paper)

978-1-60909-186-6 (ebook)

Book design by Shaun Allshouse

Cover design by Yuni Dorr

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are from the translators collection.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Names: Trubetsko , Grigori N. (Grigori Nikolaevich), kniaz, 18731930.

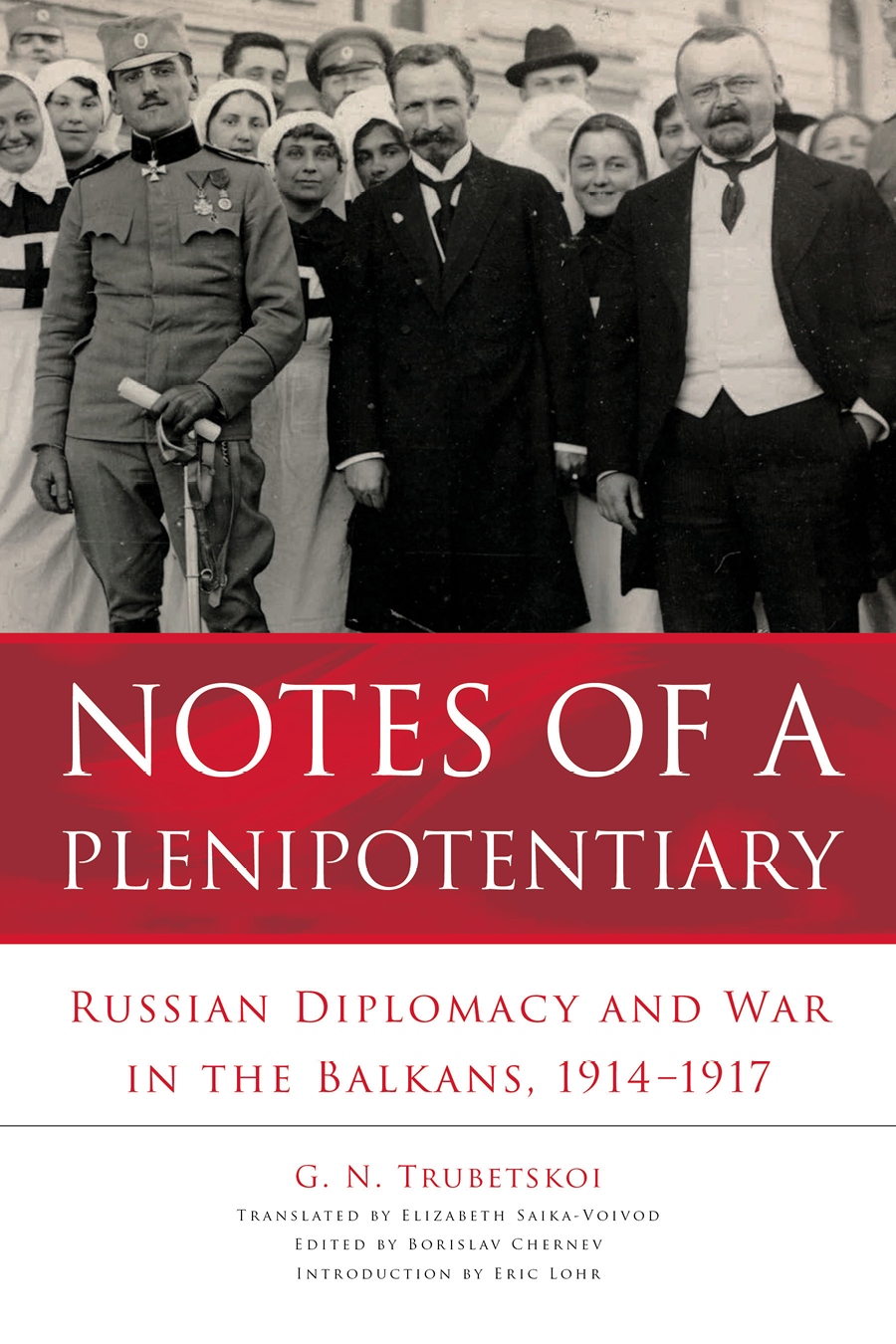

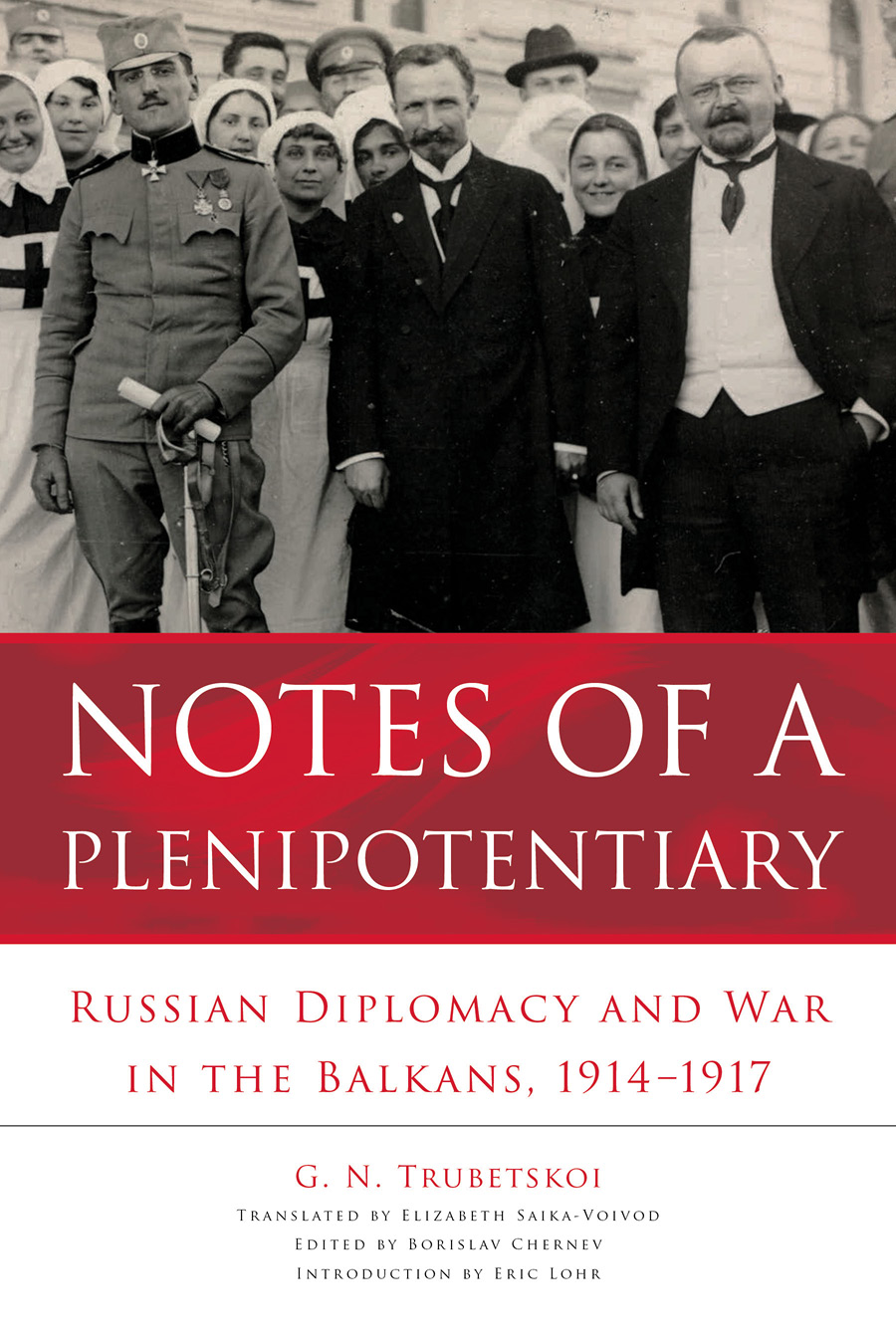

Title: Notes of a plenipotentiary : Russian diplomacy and war in the Balkans, 19141917 / G.N. Trubetskoi ; translated by his granddaughter Elizabeth Saika-Voivod ; edited by Borislav Chernev ; introduction by Eric Lohr.

Description: DeKalb, IL : Northern Illinois University Press, 2015. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015035591| ISBN 9780875807263 (paperback : alkaline paper) | ISBN 9781609091866 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Trubetskoi , Grigori N. (Grigori Nikolaevich), kniaz, 18731930. | World War, 19141918Diplomatic history. | World War, 1914-1918--Personal narratives, Russian. | DiplomatsRussiaBiography. | RussiaForeign relations18941917. | World War, 19141918Balkan Peninsula. | World War, 19141918Turkey. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs. | HISTORY / Europe / Russia & the Former Soviet Union. | HISTORY / Military / World War I.

Classification: LCC D621.R8 T78 2015 | DDC 940.3/224709496dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015035591

Contents

Grigorii N. Trubetskoi was a unique and contradictory figure in the first three decades of the twentieth century. He was a leading liberaland often scathingcritic of autocracy yet was perhaps most influential in pushing the regime toward an aggressive stand in the Balkans. Personally deeply religious and idealistic about his faith, he became the proponent of deep reforms of Orthodoxy and pragmatic solutions to the divisions between the church that remained in the Soviet Union under Patriarch Tikhon and the Orthodox in emigration. A prince in one of Russias most exalted noble families, he spent his life working long hours as a civil servant and a writer.

His Career and Background

Grigorii Nikolaevich Trubetskoi was born in 1873 to one of Russias oldest noble families, a family that traces its princely title to the twelfth-century Grand Prince of Lithuania Gediminas. Grigorii Nikolaevich had nine sisters and was the youngest of four renowned brothers. The eldest, Piotr Nikolaevich, was Marshal of the Nobility in Moscow. Sergei Nikolaevich was the rector of Moscow University, a prominent philosopher, and a popular professor. His funeral spurred large student demonstrations and proved to be an important event in the 1905 revolution. Evgenii Nikolaevich was also one of Russias leading philosophers, a professor at Moscow University, and the editor of Moskovskii ezhenedelnik , an important liberal weekly journal that published broadly on foreign affairs and other topics from 1906 to 1911.

Grigorii Nikolaevich studied in the department of history and philology, and in 1896 he defended his masters thesis on the Russian domestic situation on the eve of the emancipation of the serfs in 1861. He began his diplomatic career with a posting in Constantinople, where he served for nearly ten years. In 1901, he was promoted to the post of first secretary of the embassy in Constantinople. In 1906, Trubetskoi left his career to pursue scholarly work and public commentary on political matters, dedicating himself to work for a free liberal Russia and commenting extensively on Russian foreign policy. He contributed fifty-three articles to the liberal journal Moskovskii ezhenedelnik ( Moscow Weekly ) between 1906 and 1911 and wrote an influential long article for the collection Velikaia Rossiia ( Great Russia ) on the tasks of Russian diplomacy and its great power interests.

In this period he was both a liberal critic of the regime on questions of political freedom and domestic political reform, and also opposed the tsars foreign policy on nationalistic grounds. Trubetskois critiques of imperial foreign policy were a nuanced mix of his attraction to pan-Slav ideas and his realist views on the best ways to maintain a balance of power and avoid war. On the whole, his influence probably made it more difficult for the tsar to compromise in the Balkans when Russian and Slav interests were threatened by Austria, and thus he may havecontrary to his intentionscontributed to one of the key causes of World War I.

In 1912, Trubetskoi returned to the foreign ministry. His close colleague and friend Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov appointed him to head the Near Eastern Department of the Foreign Ministry, which was responsible for Balkan and Ottoman affairs. His influence on foreign policy during the following years was considerably greater than his title might suggest, in large part because of Sazonovs deep respect for Trubetskois opinions and expertise. Trubetskoi recalls in this memoir that he met with Foreign Minister Sazonov every day, several times a day, usually for relatively long discussions of a wide range of important matters before the minister. In June 1914, the Russian representative in Serbia, N. G. Hartwig, died unexpectedly, and Trubetskoi was immediately appointed as his replacement. Trubetskois position thus put him at the center of Russian diplomacy during the crucial period of the Russian entry into the war, and his account of this period in this book is an important source for the study of the outbreak of the war.

Among other things, Trubetskoi recounts in this memoir how he drafted the proclamation on Poland and gives an interesting account of its origins. The predominant view of the proclamation is that it was a cynical expedient to bid for Polish loyalty in the war, but Trubetskoi claims that Writing this proclamation gave me the greatest moral satisfaction of my life. He also provides a colorful account of opposition to the proclamation in the council of ministers. Trubetskoi discusses how he also wrote the appeal to the Ruthenians in Habsburg Galicia, noting that nobody liked both appeals (those who liked the Ruthenian appeal disliked the Polish appeal, and vice versa), but nobody knew that they had the same author. Trubetskois explanation testifies again to his rare combination of liberalism and imperial ambitions.

Trubetskoi is also a valuable source on the major historical problem of the entry of Turkey into the war. He seems to have been convinced that there was broad popular and elite support in Russia for conquest of the Straits and provides an inside view of his lobbying for making conquest of the Straits a strategic priority. Allied negotiations in early 1915 led to plans to occupy Constantinople, envisioning future control to go to Russia. In secret, G. N. Trubetskoi was named the future Russian commissar of the city. He provides interesting details about the agreements with Britain and France and his own preparations for the position.

The bulk of the narrative deals with Trubetskois diplomacy in the Balkans. It begins with his recollections of his role and the broader Russian diplomatic role in the complicated disputes in the Balkans in the years immediately preceding the war. He provides colorful descriptions of the major actors in the region, including the kings of Bulgaria and Rumania. He felt that, from the 1878 Treaty of San Stefano on, Russia had unduly favored Bulgaria at Serbias expense. He details the rivalries between Bulgaria and Serbia and his attempts to mediate, especially over the question of Macedonia. There is a distinct theme in his memoirs of his attempting to counter the widespread view that he was partial to the Bulgarians over the Serbs.