Published by Firefly Books Ltd. 2012

Copyright 2012 Firefly Books Ltd.

Text copyright 2012 Charis Cotter.

All rights reserved. No part of this ebook may be reproduced, scanned, downloaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Publisher. Piracy of copyrighted materials is a criminal offence.Purchase only authorized editions.

eBook version 2.0

Toronto between the wars : life in the city 1919-1939 / Charis Cotter.

eISBNs:

ePub 978-177088-068-9

PDF 978-177088-069-6

Print 1-55297-899-0

Published in the United States by

Firefly Books (U.S.) Inc.P.O. Box 1338, Ellicott StationBuffalo, New York 14205

Published in Canada by

Firefly Books Ltd.66 Leek CrescentRichmond Hill, Ontario L4B 1H1http://www.fireflybooks.com/

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the financial support for our publishing program by the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund as administered by the Department of Canadian Heritage.

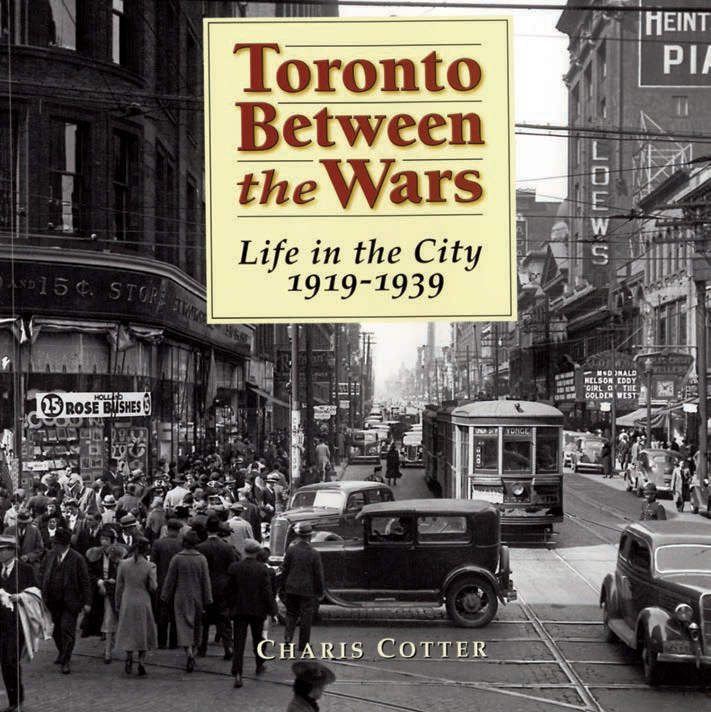

FRONT COVER: Looking north from Queen and Yonge streets, April 1938.

For my parents,

Evelyn and Graham Cotter.

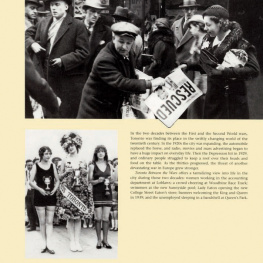

A row of rather seedy enterprises pawnshops, cigar stores, printers, a caf and the Vaudeville Theatre line the south side of Queen Street, circa 1925. This picture looks east to Bay Street, where the domes of the Temple Building are just visible. This part of Queen Street marked the lower border of the infamous Ward, home to various immigrant groups over the years.

CONTENTS

Bill Hicks, a soldier returning from the First World War, is given a royal welcome by his family and friends, circa 1919.

Aunt Eleonores house at Glengowan and Mount Pleasant Road, circa 1920s.

A child mails a letter, November 1925.

The Presence of the Past

When I was seven, my parents and I would visit my great-aunt Eleonore, who lived in a dark and beautiful house in Lawrence Park. I enjoyed these visits immensely, not particularly because of my aunt (a small, upright and large-bosomed woman who was distantly friendly though somewhat suspicious of children), but because of the house itself. It had a name a romantic, full-blown name worthy of a house in a novel by L.M. Montgomery: Wyndekrest. It was a strange name for a house squeezed in beside a bridge on Mount Pleasant Road, about six feet below street level, with the front door looking directly into the wheels of the passing cars.

When the house was built in the 1920s, Mount Pleasant was much narrower and Wyndekrest stood at the crest of a small hill, with a lovely garden around it. By the 1960s only a narrow path remained between the house and the bridge. It led down to a wild ravine, where we would go to escape the grownups.

The house had its own attractions. Overshadowed by the encroaching road, it was extremely dark. The first thing you saw as you entered the sitting room was the balding head of a real brown bear who had been made into a rug and set under a grand piano. We ventured upstairs only for the bathroom, where a silver scalloped soap dish held tiny scalloped soaps. In the dark hall, closed doors hid the bedrooms.

A desk in the sitting room had bars across the side shelves, and my small hand could reach just past them to find the Niagara Falls purse made from the two crescents of a shell hinged together. A fading painting of Niagara Falls was glued to the outside of the purse; inside were red-paper compartments and, always, one silver dime.

The kitchen had a rather neglected air: long, narrow and inconvenient, and full of shadows. On each visit we had to perform the ritual of asking Aunt Eleonore politely if we could play with the things in the hoosier (an ingenious piece of kitchen furniture that combined cupboards and counter space). She would nod her head graciously, always maintaining the upright carriage that had seen her through many recitals at the Metropolitan United Church downtown, where she had been a well-known mezzo-soprano. Then we would scatter to the kitchen, settle ourselves on the floor, and lift the latch of the hoosiers lower cupboard.

Inside were all manner of exotic kitchen utensils: fluted muffin tins, cake pans, bread pans, hand mixers and many odd-shaped metal things with funny spikes and corkscrews. What were they for? We improvised, using them to cook fancy dishes, build pyramids and towers, or wage quiet wars that wouldnt attract the grownups attention.

Aunt Eleonores house was the first hint I had of what life in Toronto had been like in the twenties and thirties. My great-uncle, a lumber merchant, bought the newly built house in 1923, and most of the dark, dignified furniture came from Simpsons, which had the reputation of being more upscale than Eatons. My father lived there with his aunt and uncle during school holidays in the 1930s. For me it was a ghostly house, full of memories and tantalizing glimpses of a life that was past. The piano and the bear underneath it were quiet, the kitchen utensils forgotten in a cupboard, the shadowy rooms silent and unused. I loved the idea that the house had once been something more, before the road had been widened, and that I was seeing only fragments of its true nature.

The presence of the past is all around us in Toronto, just as it was for me in the house in Lawrence Park. Within the modern city lie all the decades that came before. In houses, buildings, neighbourhoods, street names and peoples memories, the Toronto of the 1920s and 1930s can still be found. Landmarks that were built then are still here: Union Station, the Eatons College Street Building, the Bank of Commerce Building on King Street, Maple Leaf Gardens and the Royal York Hotel. Most of the street grid of the downtown core is unchanged. Many Toronto neighbourhoods were well established then, filled with houses that remain today. Many of the churches are still there, although some are now used as theatres, daycares or community centres.

Despite all the development of the downtown area in the last half of the 20th century, there are still traces of the Toronto that existed between the world wars, if you know where to look. But what about the people? Who were they? How were they different from us? How did they dress? How did they get to work? What did they do for fun?

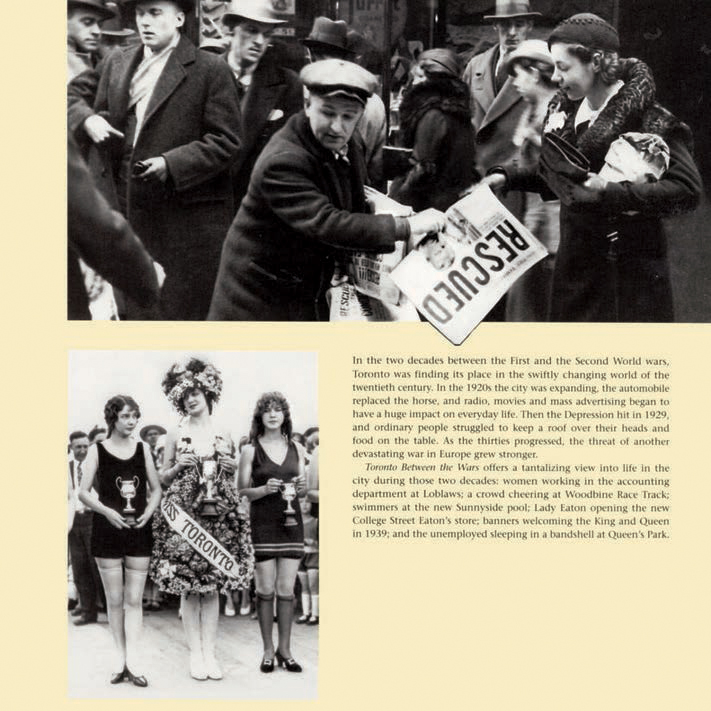

The City of Toronto Archives, particularly the James Collection, provided me with a treasure trove of pictures of people and places from the twenties and thirties. The choices of photos and subjects in this book are personal and, in some ways, arbitrary. I did not try to cover every aspect of life in Toronto during the years between 1919 and 1939. I let the pictures lead me to the stories.