These stories are pulled from my memory of them, which is as messy and imperfect as the stories themselves. Dates and dirt roads and state lines tend to fade into one another after all those years beneath the desert sun.

All two-legged characters who appear in this book have had their names changed to protect their identity.

C attle almost always walk in a line. Even the open-range ones out beyond the fences. Like trained trail horses, they trudge, head down, with the rump of another cow directly in front of them, their narrow trails weaving through sagebrush and patches of prickly pear cactus. A few bulls up in front know exactly which watering hole or feed bucket or patch of junipers they are heading toward and exactly when they expect to arrive. The rest are just in line, head down, hoping for the best.

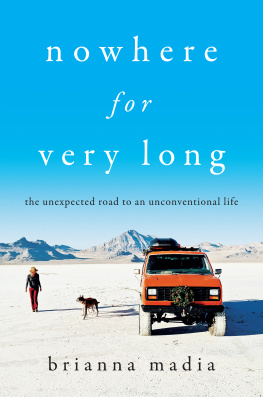

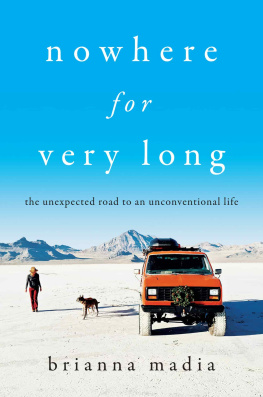

I made a mental note of this as I watched a herd of them cross the dirt road a few feet in front of my old Ford van. Her thirty-three-inch off-road tires and bright orange paint job almost offset the fact that she was about as big and reliable as a junkyard school bus. I leaned forward to rest my chin on the steering wheel, my three dogs barking wildly over my shoulder.

The midday August sun beat down on their dusty black backs; flies swarming, tails swishing. We werent going anywhere anytime soon. Not because of the cattle, of course, but because the van in which we sat had been broken down right there on that road for over twenty-four hours.

The day before, I had loaded up enough food, water, and supplies for two weeks out in a remote southeastern corner of the Utah desert. I left early, driving west from the town of Moab toward Capitol Reef along a two-lane, sun-bleached highway. After an hour or so, I hooked a hard left onto a dirt road before slowing to a halt in a plume of dust. I got out, locked the hubs, checked the ratchet straps on the roof rack, got back in, and shifted into four-wheel drive.

Forty-eight miles later and forty-eight miles from pavement, the van rolled silently to a stop in a network of desolate dirt roads. There had been no loud clanking noise, no odor of leaking fumes, no smoke from the hood. A tie rod end hadnt snapped, jerking the wheel ninety degrees and sending me skidding violently into a sandbank. Rusted leaf springs hadnt cracked in half, rendering the van slightly crooked and limp as though the passenger side had had a stroke. (All things that had already happened up to that point, by the way.) I cranked the starter a few times, pumping the gas pedal with each attempt, but there was no sound besides the cicadas buzzing in the heat.

I jumped out of the front seatstill a far fall even at my five-foot-ten statureand squatted down to look at her undercarriage. Above my head was the orange and black nameplate Id had custom-made for her front grille. Bertha. Named after my favorite Grateful Dead song.

Her front axle seemed intact. There were no hanging wires or dripping fluids. Nothing felt overheated beyond the usual searing hot steam that billows up from the belly of a thirty-year-old van. I lay on the ground and used my feet to slide myself across the sand beneath her like a mechanic without a dolly. With my eyes, I scanned all the parts I knew. The brake drums and the rotors and the shocks and the drive train and the exhaust system.

Sand from the ground stuck to the sweat on my skin even when I stood to lift the front hood. Again, I scanned. The radiator and the alternator and the transmission and the oxygen sensor. I could name all of these parts, but I couldnt repair a single one of them. That had been my husbands job, back when I had a husband. And for a girl whod traded in just about everything for that old van, youd think I would have at least bothered to learn how to fix it.

The nearest mechanic shop was 190 miles away. Thats what the woman on the other end of the phone said when I called for a tow service. I had climbed on top of Bertha to get a better signal. The operators voice cracked in and out as I paced on the roof rack next to the solar panel. She said she would contact me when she found a flatbed tow truck that was willing to make the near-four-hundred-mile round trip. She had no guarantee of when they would come or if they would come at all.

When I hung up, I felt strangely calm. I suppose when there had been two of us standing roadside with this broken van, there were sharp words and blame to throw around. He would say that I should have known the van wouldnt make it this far. I would say it would have been fine if he had fixed the right part. He would say it was my decision to live in this fucking thing anyway. And it was. It was my decision. And now it was just me left to reckon with it.

Perhaps that sense of calm came from the realization that there was no longer anyone there to say I told you so. No longer anyone there to try to convince me to give up on Bertha, because for some ungodly, inexplicable reason, I just could not give up on Bertha.

I climbed down, slid the door open, and watched the dogs burst out across the field in search of the jackrabbits that come out at dusk. They disappeared from view as I yanked the cork from a wine bottle with my teeth and took a good, long swig.

For as many times as I had watched the sun dip low in the desert, it still mesmerized me. First the pale blue turns to pink, softening the edges of all the sharp, brambly desert things. Then the reddish-orange seems to rise up from below like fire, silhouetting the hills and the junipers and the sandstone cliffs. Then just like that, it dims and fades and the dogs wander back to the van and the deep blue night drips down over us.

Even as I stood there in the middle of the road beside that giant orange mess of metal, it all seemed so peaceful. There had been no dramatic explosion, no horrible screeching car accident, no burst of fire consuming her whole. Bertha just rolled silently to a stop one day on a completely nondescript dirt road that sliced through a sagebrush field, and it was over.

That part of my life was over.

I believe the truth of how we become who we are is layered. Not like onions, but like earth. Traceable at the surface, but tumultuous beneath. Tectonic plates of our pasts shifting violently, or more often subtly, causing great rumbling disruptions in the identities we think weve mapped so well.

I didnt grow up in the desert. I didnt grow up in any kind of world where risk was encouraged, where fear was celebrated. In fact, living in an old van with only the coyotes for neighbors was a positively rebellious departure from my middle-class Connecticut upbringing. A middle finger to the only way of life Id ever witnessed. Grow up. Go to school. Get a job. Get married. Buy a house. Have some kids. Make a lot of money. Buy a bunch of stuff. Work constantly to afford all the stuff. And then hope youre still alive and able-bodied enough to go out and see the world.

Where I came from, how much you had was always more important than who you were. Wealth was not measured in the stories you could tell, but in the price of your car and the size of your house. And it wasnt ever the concept of wanting all that stuff that turned my stomach. I understood wanting; it was the sickness of wanting all that stuff so badly and so often that I might forget to go find what I needed. It was the insatiability of it all; that no amount of anything was ever going to be enough because I hadnt found what enough truly felt like. So, I set out to prove what I didnt need. My quest for simplicity started with a summer spent living on an old, mildew-covered thirty-foot sailboat before I fled west to Utah with the boyfriend who eventually became my husband. Then we made a home out in the desert in that big orange van, where the echo of our voices on the canyon walls were the closest sounds to civilization.