For my dear parents: my father, Taj Mohammad, and my late mother, Bibi Aminah, who never gave up.

For my cherished family, Davina, Zane and Alana.

And for all those who strive to make our world a better place.

Dr Waheed Arian

IN THE WARS

A Story of Conflict, Survival and Saving Lives

TRANSWORLD

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Transworld is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in Great Britain in 2021 by Bantam Press

Copyright Dr Waheed Arian 2021

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover design by Marianne Issa El-Khoury/TW

Cover photo Colin Thomas

Background imagery Getty Images

Every effort has been made to obtain the necessary permissions with reference to copyright material, both illustrative and quoted. We apologize for any omissions in this respect and will be pleased to make the appropriate acknowledgements in any future edition.

ISBN: 978-1-473-58262-0

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

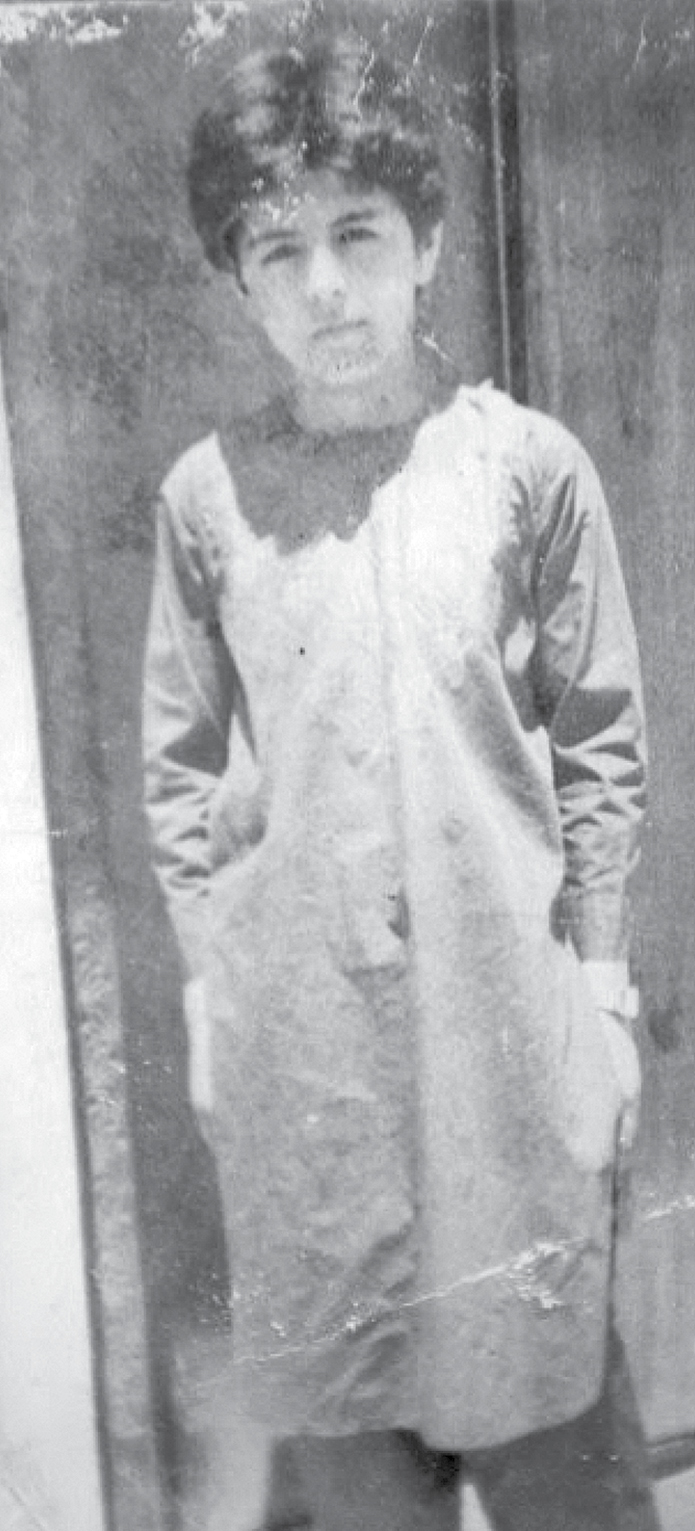

Illustrations

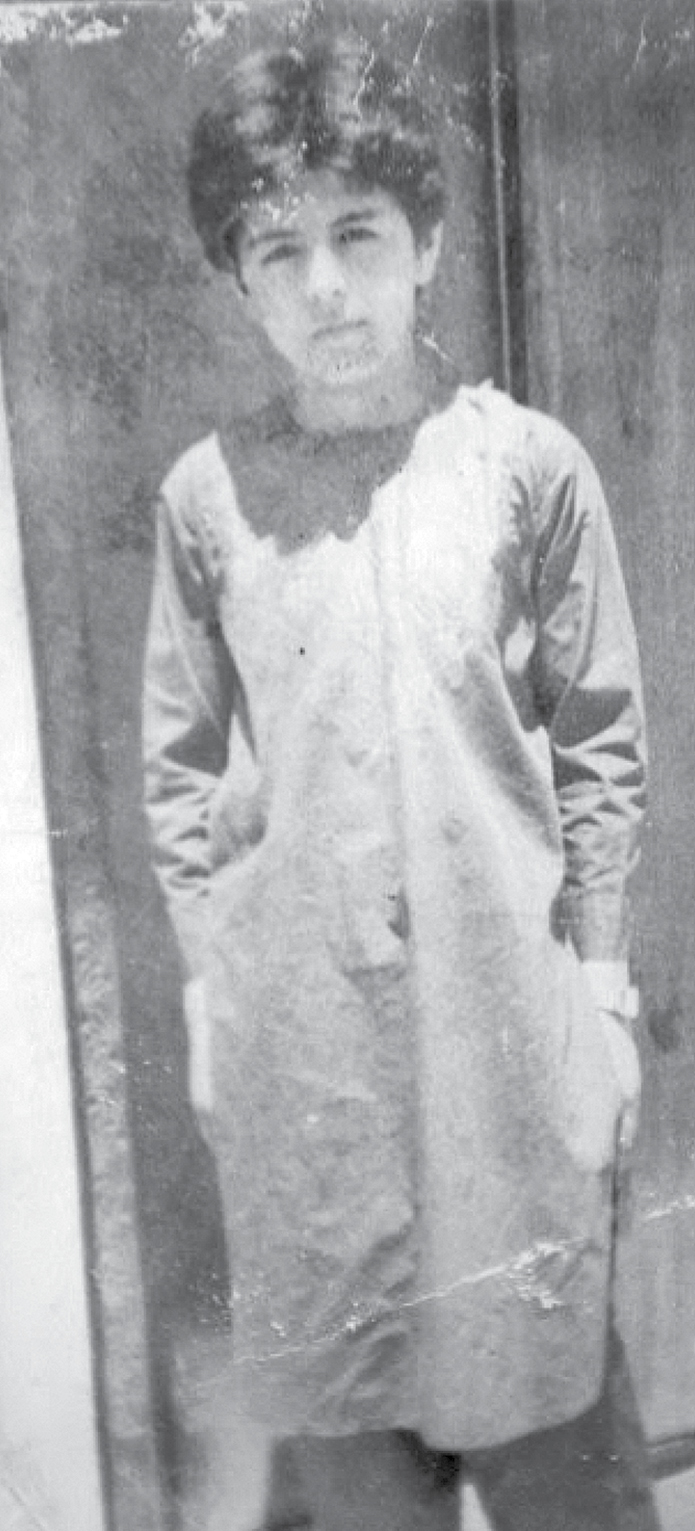

Standing outside our home in Shahre Naow, Kabul, after it was hit by a rocket early in the civil war. This photograph was taken by a UN aid worker.

One of the proudest moments of my life: graduating from Cambridge University in 2006.

Arriving at 10 Downing Street in 2018 for a reception hosted by the prime minister to celebrate the seventieth birthday of the National Health Service.

Authors Note

THIS IS A PERSONAL story. Naturally, some of my childhood experiences overlap with those of other members of my family. Some are mine alone. In this book our early family life is inevitably recalled from my perspective but we all suffered, as have the millions of people in Afghanistan, and in other countries around the world, whose lives have been blighted by conflict, displacement, poverty and oppression. Many have suffered, and still suffer, far worse than we did.

Every one of us has our own story, and the individual stories of my relatives are not mine to tell. Out of respect for the privacy of my sisters and their families, I have changed their names. My parents and my brothers are referred to by their real names.

While memories from our early childhoods tend to be random and fragmented, significant episodes leave a deeper impression and many of my recollections remain striking. Some have been pieced together from the collective family memory bank and with the particular help of my parents. Amid the confusion and trauma of war, it is hard to keep track of time, place and an ordered sequence of events, especially since Afghanistan follows a different calendar from Western countries.

Details of some events have been withheld, for legal reasons and to protect confidentiality. But everything I have recounted happened and has been recounted truthfully.

The troubled history of Afghanistan is extremely complex and the brief coverage given here is not intended to offer a complete overview. Afghanistans story is touched on only where it provides a context to my own childhood and in terms of the impact on my life of some of its key moments.

As a humanitarian, my mission is to improve and save lives, in the land of my birth, my adopted home, the UK, and across the world, irrespective of nationality, ethnicity, culture or religion. I make no apology for maintaining an impartial stance in describing the conditions, past and present, faced by Afghanistan and other countries.

The political battles are for others to fight. My purpose in telling my story is to show how standing shoulder to shoulder and working together can change the world for the better and how every one of us has a contribution to make to society. Above all, it is to inspire others to pursue their dreams.

Part One

1

Home

THE BOY WAS YOUNG, about my age. Skinny, thin, pale face, sharp nose, short, blondish hair. His blue eyes were watchful but not unfriendly. His name was Ryan, and he was my cellmate.

Why are you here? I asked him.

I steal things, mate. He seemed surprised by the question.

I was dismayed.

Id been brought to this place, called Feltham, from Heathrow Airport and had spent my first couple of nights billeted with a different cellmate: a muscle-bound man-mountain who had seemed a lot older than me, though as we were, Id been informed, in a prison for juvenile offenders, he must have been younger than he looked. He was here because he had got into a fight and beaten someone up. We hadnt spoken much: he was a man of few words and I was struggling to make sense of what was happening to me.

Ryan was more open and approachable. We talked a bit and exchanged potted life histories. He lived with his mum, who had a clerical job. It was clear this wasnt the first time he had been at Feltham.

I didnt really understand why I was here. It certainly hadnt been part of the plan three days earlier, when Id boarded a flight in Peshawar, carrying my hopes, and those of my family, for a new beginning. I had left with a brand-new UK passport, a visa and the assurance that I would be welcomed in London with open arms as a refugee. I was fifteen years old.

Instead I had been held in a cell overnight at Heathrow and told that I could expect to be in prison for a year, maybe a year and a half, before being sent home. After two days in Feltham, Id been taken in a van to some kind of courtroom and then brought back again. My attempts to explain myself had so far been ignored by everyone I had met. I just couldnt reconcile this response with the impressions I had formed of Britain and the British who, I believed, were compassionate and fair-minded, horrified by the suffering of the people of Afghanistan and ready to accept those willing to work and make a contribution to society. It was like being in the middle of one of those bad dreams where youre urgently trying to tell someone something and they just cant hear you.

I had been given this one chance to save myself from the brutal Taliban regime and ensure the survival of my family in Kabul. All the hopes invested in me were crumbling to dust; all the money scraped together, the huge sacrifice made to get me to a place of safety, where I could work to help support my mum, dad and ten brothers and sisters, pursue an education that, because of all the disruptions to our lives, had barely got off the ground and make something of myself. And the worst of it was it was my fault. The burden of self-blame weighed heavily on my shoulders. I was convinced that this would break my parents and if I couldnt get out of here I would never see them again. They would both have heart attacks and die while I languished in an English prison.

Next page