Praise for Irmas Passport

Gripping, poignant, and inspiring, this true tale illustrates how pride can help to power through suffering and create meaning. Author Catherine Ehrlich, drawing heavily on vivid memoirs written by her grandmother, has added depth of research, beauty of language, and a haunting present-day perspective to the life of an extraordinary woman of Vienna during wartime and beyond.

DORI JONES YANG, author of When the Red Gates Opened: A Memoir of Chinas Reawakening

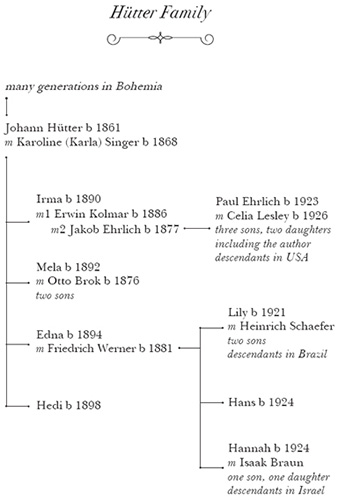

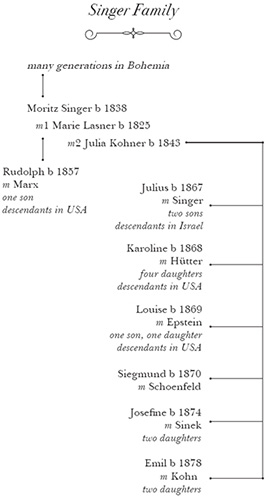

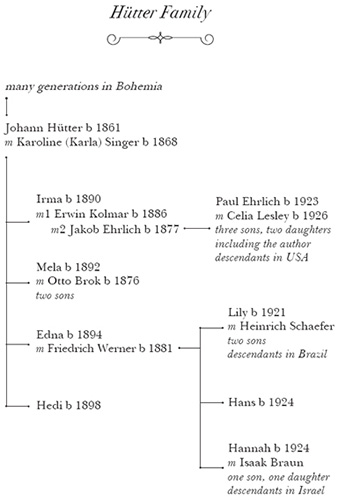

This beautifully written combination of a Holocaust survivors memoir with the recollections and research of her granddaughter captures the charms of fin-de-sicle Bohemia and the devastation that followed. Imaginative, compelling, clear, and touching, the narrative of an emancipated and educated womans heartbreak during the First World War, new love and hope in 1920s Vienna, despair again as the Nazis closed in, and escape with her only son to America illustrates the human cost of intolerant and violent politics in Central Europe. Irmas Passport, a new addition to the vast literature on fascism and anti-Semitism, deserves attention from readers of all ages.

JEREMY KING, Professor of History, Mt. Holyoke College

A gripping and well-written story about a courageous woman living between the world wars. Irma is a spitfire of a woman who attended university when there were only 4 percent women students, and who shared an English literature class with Franz Kafkahistorical figures pop out like gifts in the story. The book also provides a window into the assimilated life of the Jews of Bohemia, early Zionism, Antisemtism, and the Holocaust. Your foreknowledge prepares you for what is coming but, inspired by Irma, you hold your breath and read on.

LEORA KRYGIER, author of Do Not Disclose: A Memoir of Family Secrets Lost and Found

Irmas Passport

Copyright 2021, Catherine Ehrlich

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, digital scanning, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law. For permission requests, please address She Writes Press.

Published 2021

Printed in the United States of America

Print ISBN: 978-1-64742-305-6

E-ISBN: 978-1-64742-306-3

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021907686

For information, address:

She Writes Press

1569 Solano Ave #546

Berkeley, CA 94707

Interior design by Tabitha Lahr

She Writes Press is a division of SparkPoint Studio, LLC.

All company and/or product names may be trade names, logos, trademarks, and/or registered trademarks and are the property of their respective owners.

Contents

Irma and Catherine share-wear Irmas Austrian folk ensemble with edelweiss trim, early 1970s

Prologue

Irma and I

M y grandmother, Irma Ehrlich, was nearly eighty-two years old in 1971 when she flew from Manhattan to join me in Hokkaido, the northernmost island in Japan, where I was living as a seventeen-year-old exchange student in the Buddhist temple compound of my host, Ryuei Hata.

Irma sat in the one Western-style chair in Hatas tatami sitting room, her sturdy calves crossed and her dandelion puff of hair pale in the dimming light. Hata and I gathered nearby on floor cushions beside the wide window overlooking Ishikari Bay. Nightjars scythed through the sky after insects as we gazed over blue and red rooftops to the harbor below, watching the last ferryboat glide in like a glowing caterpillar from forbidden Vladivostok.

Vladivostok, Irma was saying, was where her brother-in-law, Fritz Werner, was imprisoned when he was captured just four months after the start of the Great War in 1914. Hed survived on packages delivered by the Red Cross and kept up hope by learning languages from fellow prisoners. After the war ended in 1918, it took him four years to wend his way back overland to a newly minted country called Czechoslovakia. When he knocked at his front door after nearly eight years of bitter hardship, his wife, Irmas sister, couldnt recognize him at first. Irma paused. The nine languages Fritz practiced in prison became his passport to a good job in business, she concluded.

Hata rolled back on his cushion with the audible air intake that is Japanese for amazement. The dignified woman in his guest chair was older and stronger and worldlier than anyone in his Pure Land Buddhist congregation, and she brought faraway empires right into his home. As for me, Id always known Irma as old and strong and spellbinding. A prompt like Vladivostok locked behind the Iron Curtainwas sure to bring forth tales of miraculous escapes, of families reunited, and of great wealth lost and restored. Her stories often seemed to say Dont lapse into victimhood; use languages as your passport to the world, and I had absorbed the lesson. Id spent countless hours after school studying Japanese while feeling captive as a restless teen in Buffalo, New York, before winning the Rotary Club scholarship to live abroad. Without my knowledge, Irma paid for my flight to Japan.

In my childhood I believed my grandmas promise that she would put me in her suitcase and take me abroad. I imagined myself curled up like a kitten, keeping silent to avoid capture. We shared the secret bond that exists between redheads: something rare, aligned, unspoken. Her example planted in me the notion that a woman could achieve mastery in foreign languages and belong wherever she lived. In Japan, I believed that my fluent Japanese and immersion in the country could make me Japanese, and like her I didnt conceive of race or religion as a barrier to belonging.

She knew eight languagesCzech, German, French, Italian, English, Latin, a little Hebrew, and some Turkish. Shed attended Charles University in Prague in 1910 as one of its first female students, crossed Alpine glaciers in ankle-length leather skirts in the 1920s, and rebuilt her life after two devastating European wars. Language mastery and indomitability had carried her through. I thought of her as unembittered, unbowed, victorious.

When she was my age she was a milky-skinned, golden-haired girl in a storybook place called Bohemia, dreaming of a larger stage for her life. In her early eighties she flew halfway around the world to join me and climb the 1,368 steps of Konpira-san shrine while Japanese pilgrims half her age labored haltingly. We inhaled the scents of azaleas and wet moss at golden Kinkaku Temple and marveled at ancient ink scrolls. Irma and I floated in pale blue mist in a light blue boat across deep blue Lake Hakone, joking about feeling bluish. Bluish, a sort of color, a play on being sort of Jewish. I never felt Jewish. That part of my heritage belonged mostly to the past, I thought, in those bygone places like Austria-Hungary and Bohemia. I loved to hear her memories of exotic times and places, though I struggled to keep her stories straight. Someday, she said, she would retire from her job at a law office in New York and write her memoirs.

Next page