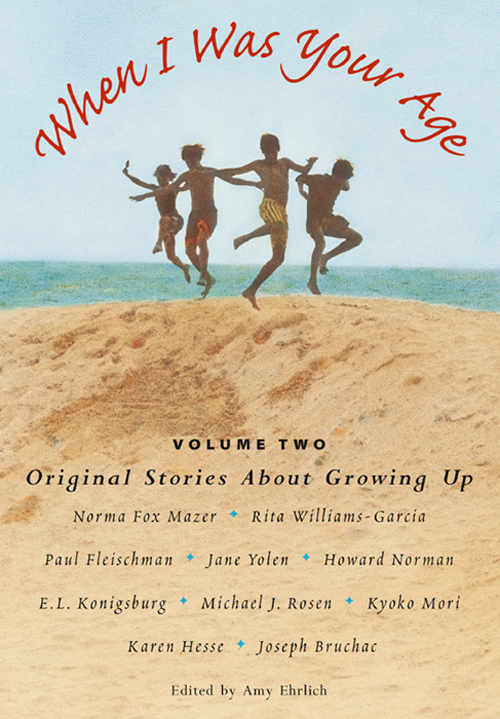

When I Was Your Age, Volume Two has given me the great pleasure of editing a second group of stories by childrens authors about growing up. Ive now worked on twenty of these twenty stories about twenty childhoods, twenty different ways of seeing and being in the world.

It stands to reason that every single person is unique, but when you ask twenty authors the same question: What was it like when you were a child? and get answers that are so wildly different in content and tone, it makes you look at other people in amazement. How have we come to be together? How do we even manage to communicate?

But the ten stories in When I Was Your Age, Volume Two (and those in the first volume as well) chart a clear and certain path through the forest of human differences. It is simply this: we are all different, we are all human, and if we tell the truth, we will be understood.

The authors in this collection have been honest and generous. They have shown us how theyve managed not only to survive their childhoods but to treasure and even to laugh at them. If you read the notes at the end of each story, I think you will see an almost seamless connection between the authors stories and the rest of their lives. These people these children who grew up to be authors write because they need to. By exploring the past with words, they can give form and meaning to their own experiences.

And what are these experiences? I think I can tell you a bit about each story without giving too much away. Rather than attempting to analyze anything, Id rather tell you what I most love about each authors writing. That way, Ill be able to enjoy it all over again, and perhaps you will too.

Norma Fox Mazers In the Blink of an Eye pulls us right into her world. Here is Norma, vivid from the very first sentence, all her nerves jangling: In the gutter, a lit cigarette butt catches my eye. I swoop for it, stick it in my mouth, and take a puff. It tastes like dirty straw; still, I suck deeply, as Ive seen my father do. Outside in the street Norma is tough, a tomboy, but at home she cant seem to stop crying. There goes the faucet, her family say. Shes so sensitive... too sensitive. How lucky though for the rest of us that she was! It must be because Norma feels things so deeply that her writing is so full of feeling.

Rita Williams-Garcia, as we meet her in Food from the Outside, is another case entirely. Her response to life is not to cry about it but to take action. Laughter, nerve, jive, and guile are how Rita, her brother, and her sister get around their strict, opinionated mothers rule never to eat at anyone elses house. Rita explains it with a comics deadpan timing: You see, our mother, known throughout the neighborhood as Miss Essie, was still refining her cooking skills. The childrens elaborate efforts to outsmart Miss Essie make their lives seem more fun and eventful than the situation comedies they watch on TV.

Paul Fleischman had no such obstacles to contend with. As he himself admits, I lived in comfortable circumstances in beautiful Santa Monica, California, ten blocks from the beach, amid a loving family, in a time of peace... But all that meant nothing. Why? Because throughout his school years he suffered from CSD, Chronic Stature Deficiency. Paul Fleischman was a shrimp.

Im quoting from Pauls introduction to his story, Interview with a Shrimp, which is set up in a journalistic question-and-answer format. To me, the fact that Paul has chosen such an approach to writing about his childhood confirms one effect of his shortness. Having a special vantage point, being different, helped to make him an original thinker and eventually a writer.

Pauls story is also unusual in providing an overview of an entire childhood. Most of the stories in the book focus on a single dramatic incident, perhaps because thats the way experience is imprinted in our minds. Things that were upsetting or unresolved at the time stay with us.

Jane Yolens The Long Closet is just such a memory it begins with a mystery and ends with a terrible discovery. One night when she is sleeping in her grandparents house in Virginia, an insistent, sighing sound wakes her. In this story a tale of suspense, really we are with Jane every moment, afraid to find out what the sound is, yet pulled forward by it. Everything is described with nerve-racking slowness. The room was filled with that lovely, scary early morning half-light you get in the South; shadows of the tall pines seemed to creep around and about the wainscoting on the walls. The sound came again, and I realized it was coming from the long closet.

How does a writer re-create the past and give it over to us fresh and new and shining in the present moment? I think detail of the senses what is seen, heard, smelled, felt is the only answer. Draw a picture in words and make it real. This is just what Howard Norman does in Bus Problems, when he describes the bookmobile in Grand Rapids, Michigan, where he worked every weekday in the summer of 1959.

We know just by the quality of Howards writing and also because he does tell us so that for him the bookmobile was an enchanted world, a secure and peaceful place. We can see the leather benches mended with masking tape, and feel the heat of the day outside. Its as if the story has opened on an empty but familiar stage, then suddenly onto it leap the most amazing characters, and the drama begins.

If a child is lucky, there is always shelter, a place that is yours alone. For Michael J. Rosen, that place was on the back of a horse. Id climb in the saddle, and instantly, other riders, other horses in the ring, whatever it was I didnt want to do after camp or beginning in September... it all ceased to exist, along with the rest of my life on the ground, shrinking, fading behind the trail of dust the horse and I made heading to the horizon.

What I most appreciate though about Michaels story Pegasus for a Summer is the vulnerability and longing it conveys. He bravely wears his heart on his sleeve, letting us see so clearly his need for approval, for love.

All children certainly need these things, and the degree to which they get them, or dont, depends on their families. But children can sometimes be wrong about how their families feel about them, as E. L. Konigsburg wryly demonstrates in How I Lost My Station in Life. There were two daughters in the family, Elaine (E. L.) and her sister Harriett, and it seems that Elaines role was (1) to be the baby of the family and (2) to get all As in school. Everything was going along fine until (1) they moved in with relatives who had a child younger than she was and (2) she had to go to a new school, where the teacher... asked the wrong questions for the answers I gave.

Behind the specifics of Elaines plight is a bright childs need to do well so that others will love her and also for its own sake. It is this latter aspect that can serve us, once we learn it, for our entire lives.

So many of the stories in the collection appear to be about achievement but arent really. In Kyoko Moris nearly bottomless Learning to Swim we easily understand her desire to please her wonderful mother by earning red or black lines on her bathing cap each representing a certain number of meters swum in the school pool. The events in the story take place in Japan and there is a controlled, matter-of-fact tone to the writing that seems a part of this distant culture, yet we can still see in each speech and gesture all that her mother does for Kyoko and how deeply she is loved.