Tell me a story of when you were a little boy, I used to ask my father, when I was a little girl. Because he happened to be a writer, the stories he told were more romantic than fairy tales, more exciting than TV adventure dramas. Maybe they were even true!

Thats what we did when we put together this collection: We sent letters to all of the writers, asking them for stories. If you are interested in this project (we said) the story you might choose to tell doesnt have to be literally true in every detail but should be located in time and space in your own childhood. It can be dramatic or serious or funny whatever tone is right for the characters and plot.

Each story that came back amazed us. Each was completely different from the others and yet they had so much in common. Perhaps this is because all these writers (and the rest of us too) share childhood itself a rich and important time in a human life.

Time moves more slowly in childhood. Thats probably hard to realize when you are living through it, but think for example how long a summer seems between one school year and the next. The quality of what you see and feel is more vivid too in childhood. When you are very happy or very sad, those emotions color everything. Some of the experiences you are having, even right now, may remain with you always as memories.

Several of the stories in this collection take place more than half a century ago. Television had not yet been invented, and radios and phonographs were the only entertainment in peoples homes. There was no MTV, no video arcades, no malls. World War II was going on, yet children played without fear on city streets. Life was very different, but through the lens of the storyteller, you can see what it felt like to be a child in this vanished world.

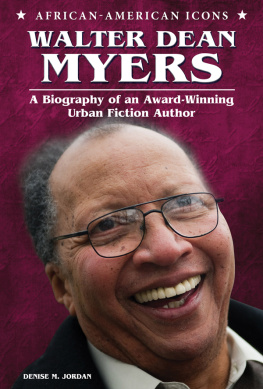

Walter Dean Myerss Reverend Abbott and Those Bloodshot Eyes will take you to Harlem in New York in the late 1940s, when every mother on the block would keep an eye on all the children and holler if anyone misbehaved. And with the boys in Avis story Scouts Honor, you can take the subway all the way from Brooklyn to Manhattan and walk across the George Washington Bridge, afraid not of muggers but only of dishonoring yourself in front of your friends.

For all the writers in this collection, the places they describe so vividly are the places where they grew up. These are special places yet ordinary; taken for granted at the time but etched and glowing in memory. Quite simply, they are home.

Listen to Mary Pope Osborne in her story All-Ball describe the army posts of the 1950s: I loved the neat lawns, clean streets, trim houses, and starched uniforms. I loved parade bands, marching troops, green jeeps, tanks, and transport trucks.... Living on an army post in those days was so safe that in all the early summers of our lives the children of our family were let out each morning like dandelions to the wind.

Just as home is the place known best, so are childrens families the center of the world in these stories. In fact, more than half of them are about a childs intense love for another family member , especially a parent. Most often, this beloved person understands the childs longings and responds in a full and loving way.

In Reeve Lindberghs Flying, another kind of understanding is involved. When her aviator father tries to teach his children about airplanes by taking them up in a small plane on Saturday afternoons, the lesson instead is about what flying means to him.

Brothers and sisters too particularly older ones can be a powerful influence on children. In Katherine Patersons Why I Never Ran Away from Home, set in wartime China, it is her bullying big sister Lizzie prettier and more talented (or so the narrator thinks) who stops her from doing something disastrous.

But a familys love can also be destructive. In some of the stories, children are very needy and vulnerable, and the writers show that if parents or brothers or sisters ignore this, the child can be badly hurt.

In Francesca Lia Blocks Blue, a girls father, sad and distant since his wife deserted them, does not see his daughters despair until it is almost too late. And in James Howes Everything Will Be Okay, a boys longing for a stray kitten collides hard with his brothers code about toughness.

In fact, the need to be tough is a strong undercurrent to many of the stories in this collection. Despite environments that are often safe and welcoming, the cruelty of other people particularly people their own age exposes children to danger and sometimes makes toughness the only possible response.

Taunts like Crybaby, Stupid, Wacko, and Sissy; and phrases like I felt lonely, I was scared, I couldnt stop crying come up in these stories repeatedly. Childhood can be a harsh and friendless time.

In Susan Coopers wartime story Muffin, a schoolyard bully called Fat Alice scares Daisy, the heroine, far more than the bombs falling in England during the Blitz. Fat Alice is truly evil; her meanness has no apparent motive or cause. She kicks, trips, shoves, and pinches while the adults are busy elsewhere.

What is a child to do against such terrorism? Resourcefulness is certainly required. But so too is real certainty and self-confidence. Throughout this collection, the question of identity what it is and how you get it comes up over and over again.

In the stories, children define themselves by their similarities and differences to their siblings and parents. In Nicholasa Mohrs Taking a Dare, for example, it takes real nerve for the narrator to find her own path between her mothers intense and unquestioning Catholicism and the atheism of her socialist father.

But there are times when children, for their survival, must move away from their families and carve out new identities all their own, and this is a process that does not seem to come easily.

In fact, most of the stories in When I Was Your Age have some emotional pain in them. Their child heroes are self-conscious or ill at ease in the world. Some suffer at unfair circumstances (such as the death or disappearance of a parent), while others are just simply filled with pain crying and miserable and alone. Different.

What is the answer? What can children do aside from learning to be tough, which is only a temporary or at best a partial answer? I believe that an uncanny number of the stories in this collection show another more creative path the transformation of suffering through art.

Clues to it are everywhere in the stories. But perhaps the clearest comes from Francesca Lia Blocks Blue. In the end, it is only when the heroine, La, writes about her vanished mother that her terrible pain stops. The words she writes also have the effect of connecting other people to her:

Daddy, La said.

When she handed him the story, his eyes changed.

Its about Mom, La said, but she knew he knew....

Thank you, honey. He looked as though he hadnt slept or eaten for days. But he took off his glasses then, and La saw two small images of herself swimming in the tears in his eyes.

Where does writing begin? What is it that shapes writers? If we want to look for the seeds of it in childhood, I think this collection makes it clear that they have probably been there for a very long time.

Isolation and separation can be bridged by language. Words can cross time and distance, connecting people of different generations and ages and experience. As you read the stories in