First Mariner Books edition 2019

Copyright 2018 by Keith OBrien

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to or to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 3 Park Avenue, 19th Floor, New York, New York 10016.

hmhbooks.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

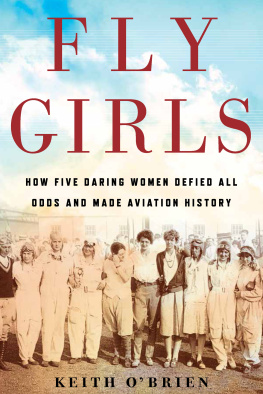

Names: OBrien, Keith, 1973- author.

Title: Fly girls : how five daring women defied all odds and made aviation history / Keith OBrien.

Description: Boston : Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2018. | An Eamon Dolan Book. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017058447 (print) | LCCN 2018026392 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328876720 (ebook) | ISBN 9781328876645 (hardcover) ISBN 9781328592798 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Women air pilotsUnited StatesBiography. | Air showsUnited StatesHistory.

Classification: LCC TL 539 (ebook) | LCC TL 539 . F 549 2018 (print) | DDC 629.13092/520973dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017058447

Cover design by Martha Kennedy

Cover photographs courtesy of St. Louis University Libraries (aviatrixes) and chanuth/iStock/Getty Images (sky)

v2.0219

Introduction

I N 1926, THERE were countless ways to die in an airplane. Propeller blades snapped and broke, and planes went down. Wings failed, folding backward or tearing away completely. Control sticks got stuck, sending airships hurtling toward crowds or hangars. And all too often, engines just stopped in midflight, forcing pilots to scan the ground below for a farmers field or a cow pastureanyplace where they might land in a hurry. In such a crisis, there is no time to think, said one early pilot. You either automatically do the right thing or you die.

In clear skies, pilots often made the wrong choice. In bad weather, they had even fewer options. Storms, squalls, rain, snow, and fog made flying almost impossible. In open-cockpit planes, raindrops felt to pilots like little bullets hurled at their faces at a hundred miles an hour. Goggles fogged up, paper maps blew away in the wind, and aviators became disoriented. A pilot, in moments like these, was instructed to find railroad tracks on the groundthe only discriminable object in an absolute gray of land and skyand follow them. By doing so, a lost flier could find the nearest town. But flying at a hundred and twenty miles an hour just fifty feet off the tracks was treacherous too. In one such case, a pilot plowed his plane into a mountainside when the railroad entered a tunnel. Worse still, pilots could do everything rightnavigate through the fog, dodge the mountains, survive emergency landingsand still lose, for reasons out of their control. In the 1920s, plane builders typically used wood to construct their machines, then stretched linen over the wings, like pillowcases, and pulled the thin fabric tight around the spruce spars. These lightweight materials, covered in a protective lacquer, helped make flying possible. But the wood could rot and the fabric could tear, dooming even the best fliers. As one aviation manual pointed out, Many pilots have been killed in wood fuselage ships.

Crashes in 1926 killed or injured 240 peoplea small but significant number, given that the vast majority of Americans never flew and that the government couldnt be sure that it was counting every accident. Federal agents gathered their figures not from official calculations but, often, from newspaper reports. Plane manufacturers had no required regulationsand instructors, no required training. Flying, one pilot noted, is no place for slovenly methods or ideas. And yet, more than two decades after the Wright brothers first flew at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, the slovenly climbed into cockpits every day, frightening the public and, at times, even themselves. Would you ride in a lot of planes you know or with some of the pilots you know? one man asked his fellow pilots at the time. You know you would not. It was too dangerous. Even the so-called aviation experts were often unable to explain what caused planes to crash. Investigator: Plane went into ground, nose first, causing complete wreck, so that it is hard to really tell what happened. Investigator: The reason for failure is hard to ascertain. Investigator: Completely destroyed by fire.

By the mid-1920s, the fledgling aircraft industry, eager to prove planes were safe, latched on to one idea capable of creating positive news coverage, marketable heroes, and excitement all at once: plane racing. Small affairs at first, the events quickly grew until pilots were competing against one another for headlines, fame, and the equivalent today of millions of dollars in what became known as the National Air Races. Soon, air-minded Americans werent just reading about their favorite pilots darting across the ocean; they were watching them whip their planes around fifty-foot-tall pylons at these races or hearing them scream across the country in one race in particular: the greatest test of speed, strength, and skill financed by important men with large egos, the Bendix Trophy race. It has become, one pilot said of the Bendix, one of our national institutions, like the World Series.

These races were often fatal for pilots. Too risky for discerning men and, according to many men and the media, no place at all for women. In the late 1920s, newspapers and magazines routinely published articles questioning whether a woman should be allowed to fly anywhere, much less in these races. That such questions could be posedand taken seriouslymight strike us today as outlandish. But they were all too typical of the age. American women had earned the right to vote only a few years earlier and laws still forbade them to serve on juries, drive taxicabs, or work night shifts. It is not surprising, then, that the few women who dared to enter the elite, male-dominated aviation fraternity endured a storm of criticism and insults. They werent aviators, as far as the men were concerned. They were petticoat pilots, ladybirds, flying flappers, and sweethearts of the air. They were just girl fliersthe most common term for female pilots at the time.

But in 1926, a new generation of female pilots was emerging, and they refused to be pigeonholed, mocked, or excluded. Instead, they united to fight the men in a singular moment in American history, when air races in open-cockpit planes attracted bigger crowds than Opening Day at Yankee Stadium and an entire Sunday of NFL gamescombined. These were no sweethearts, no ladybirds. If the women aviators had to have a name, they were fly girlsa term used in the 1920s to describe female pilots and, more broadly, young women who refused to live by the old rules, appearing bold and almost dangerous as a result. As one newspaper put it in the mid-1920s, The people are exhorted to swat the fly, but it is safer to keep your hands off the fly girl.