This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our bookspicklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1927 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2016, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

THE MEMOIRS OF QUEEN HORTENSE

PUBLISHED BY ARRANGEMENT WITH PRINCE NAPOLEON

EDITED BY JEAN HANOTEAU

TRANSLATED BY ARTHUR K. GRIGGS

VOLUME I

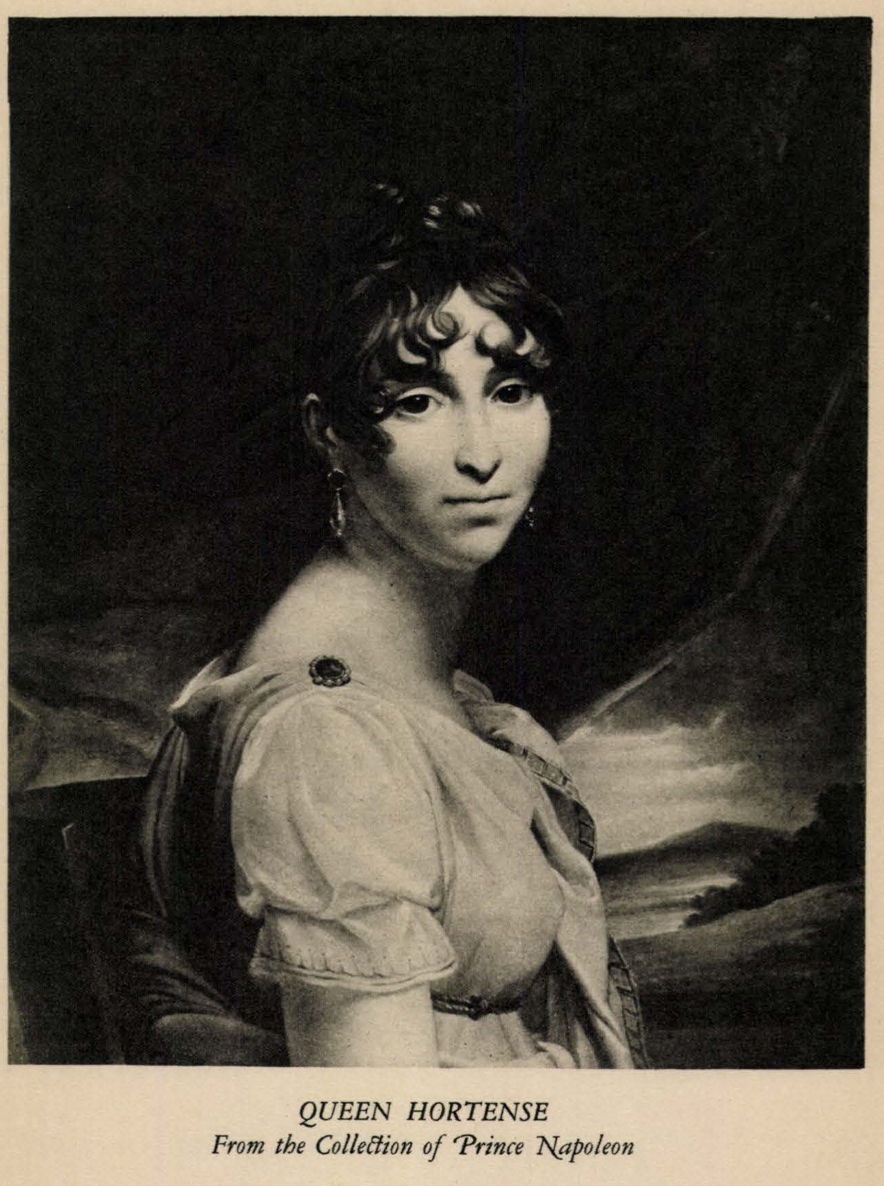

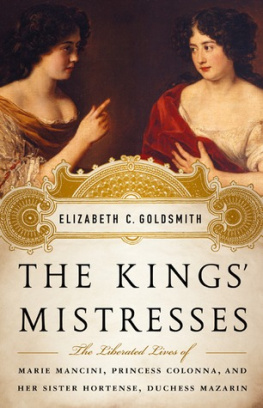

ILLUSTRATIONS

Queen Hortense

Josephine Marble bust by Bosio

Bonaparte Portrait by Raffet

Louis Bonaparte Portrait by Girodet

One of the Drawing Rooms at Malmaison

A Facsimile Page of Manuscript from the Memoirs of Queen Hortense

Napoleon Charles, Prince Royal of Holland Portrait by Grard

Fan Presented to Napoleon

Napoleon Drawing by Queen Hortense

Madame Mre Portrait of Napoleons Mother

Prince Napoleon Louis Water-color by Queen Hortense

The Royal Palace of Amsterdam

PREFACE BY THE EDITOR

I

After the return of the Bourbons and following the Emperors departure for Saint Helena, Queen Hortense, guilty, as the Duc de Vicence put it, of bearing a name which still caused the universe to tremble, wandered about for a long time in search of an asylum. In December 1815 she believed she had found a welcome refuge at Constance in the Grand Duchy of Baden. But the hatred of the Allies was still watchful. In spite of the Grand Dukes personal sympathy for her, as well as that of the Grande Duchesse Stphanie de Beauharnais, the diplomatic intrigues of the Holy Alliance made this retreat a precarious one. On February 10, 1817, the Queen bought the castle of Arenenberg on Lake Constance. But even her rights to possess this little corner of land were contested. Finally the loyal friendship of the King of Bavaria allowed the stepdaughter of Napoleon to acquire the Hotel de Waldeck, in the rue Sainte-Croix at Augsburg. She settled there on May 6, 1817.

It was at Constance during that mournful winter of 1816-1817 while her fate was still undecided that the Queen undertook to compose her memoirs.

Endowed with an extremely sensitive nature and like her mother animated by a constant desire to please and to gain peoples affection, Hortense suffered from the slightest unfavorable criticism. Because of her kindness of heart, because she knew that she had never consciously harmed anyone, she wished public opinion to judge her always on her merits. Fifteen years of public life had not steeled her against malicious scandal-mongering. She made the mistake of believing that the latter was due entirely to ignorance of the truth. Her friends had changed her motto, Least known, least annoyed into Better known, better loved, and she joyfully had adopted the new phrase.

Thus it was natural that having found a refuge and impelled by her desire to justify her conduct she should spend long hours in trying in various ways to make herself better known.

Already at the time of the imperial divorce, hearing someone blame her brother for having consented to itit is Hortense herself speakingsurprised by the difficulties truth encounters to make itself widely known she had noted down the details of the event but had not gone any further.

It was in 1812 while the Queen was taking the waters at Aix-la-Chapelle that the Comtesse de Nansouty had urged her to write the story of her life.

When Hortense declared she would not have the patience to do such a thing the Comtesse de Nansouty proposed to record what she would tell her. The next dayas is stated farther on in the text of the memoirsshe brought me what I had told her the day before about certain incidents in my childhood. But it was not like me. While admitting the merits of this account I declared I did not care to hear myself using any other words than my own, and the volume went no further than the first page, which she kept.

Louise Cochelet, who was a faithful although not always a very well-inspired friend of Hortense, relates how, at Constance, the pages were composed which now are being published in accordance with the wishes of Prince Napoleon. The Queen as usual spent the morning at home, working alone. It was at this time that the need to refute the lies and slanders which had appeared during the last two years suggested to her the idea of writing her memoirs. She felt as if it were a moral duty to describe events as they had occurred, to reply victoriously to the libelous accusations which had been brought against the Emperor. The misinterpretation of his motives, the distorted accounts of his actions could not better be set right than by someone who, having always lived near him, knew his ideas and his character.

As for the malicious gossip of which she herself had been made the object she felt so far above such base libels that, in order completely to annihilate them, all she had to do was to tell the truth about what actually took place and set down on paper a simple record of her conduct. This having been accomplished she felt relieved and thought no more about it. {1}

Mademoiselle Cochelet adds, The memoirs of the Queen begun at Constance in 1816 will not see the light till after her death. She had continued them, turning back to the years previous to that in which she began them. It is a legacy she is preparing which she will leave to historians whom time shall have rendered impartial. {2}

The Queens manuscript is dated Augsburg, 1820. This date is that on which she completed it. But on November 19, 1830, Mademoiselle Valrie Masuyer, who had just assumed the post of reader to the Queen, in telling how the latter organized her life in Rome writes: She wishes to stay at home till three oclock every day in order to go over again the memoirs she began in 1816 and abandoned in 1820. {3}

In 1833, Buchon, the scholar who spent a winter at Arenenberg, also said: Sometimes the Queen devotes her leisure to adding a page to her memoirs, which are a sort of monologue in which the soul expresses itself without fearing a strangers glance. {4} Numerous traces of these revisions, as will be seen later, are to be found in the original manuscripts.

The memoirs which follow are not the only effort on the part of the Queen to re-establish the truth.