Published by The History Press

Charleston, SC

www.historypress.com

Copyright 2018 by Katharine Seaton Squires

All rights reserved

First published 2018

e-book edition 2018

ISBN 978.1.43966.470.4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018936088

print edition ISBN 978.1.46713.967.0

Notice: The information in this book is true and complete to the best of our knowledge. It is offered without guarantee on the part of the author or The History Press. The author and The History Press disclaim all liability in connection with the use of this book.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

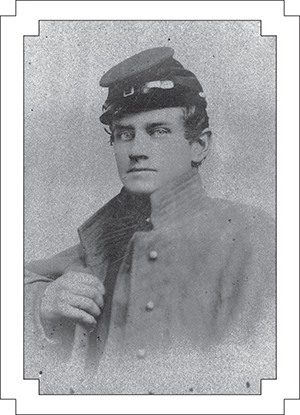

James Howard Lowell, Manassas, 1862. Courtesy of Allen Sewell.

Foreword

THE WEST OBSERVED

The westward expansion of the United States during the nineteenth century was arguably the most defining event in American history. Between the 1849 California gold rush and the advent of the railroad in the late 1860s, some 500,000 Euro-Americans walked or rode to California, Oregon, and other points west. Merrill J. Mattes, historian of the trails those travelers forged, has estimated that only one in every 250500 people left a written record of the experience. That so few people wrote about traveling as many as two thousand miles across a foreign and demanding landscape filled with perils in pursuit of an unknown future seems astonishing today, when self-documentation has become a lifestyle. But it is a revealing statistic, one that testifies to the cultural and psychological impact of literacy and mass media. In the mid-nineteenth century, most Americans had little formal education, and few developed the kind of self-consciousness about their place in the world that we now take for granted.

James Lowells reminiscent account of his participation in the postCivil War migration west is a welcome addition to the slim corpus of surviving diaries and journals, many of which have been published in recent decades. Like Lowell, most immigrants were young men bound for mining camps in the intermountain west. But Lowell differed in ways that shaped both his experience and his narrative. Relatively well educated, Lowell read widely, wrote well, and carried with him letters of introduction. His friends and associates were professionals; Lowell himself would become an attorney. Once across the Missouri River, he joined a tacit class of gentlemen, placing him among social and civic leaders in frontier settlements and broadening his prospects beyond mining and hunting. Ultimately a teacher, county official, and attorney in Fort Benton, Montana, Lowell wrote that he felt an exultation at contributing to the up building of a community or State.

Yet Lowell was an adventurer, not a settler, and his experiences were remarkable. He was a veteran of the Civil War. Like Jack Crabb in the film Little Big Man, the westering Lowell moved from one circumstance to another, changing personas and meeting an unfolding series of historical actors. His recounting of these experiences is sometimes cinematic and begins en medias res: One day in April 1865, I was pacing the platform of a railway station in Pittsburg, Pennsylvania, and counting the number of planks thereof, for I had nothing else to do while waiting for a westbound train. Moments later, he happened to meet the future territorial governor of Utah, the first of many influential people he encountered during his six-year sojourn in the West. Among them were politicians, entrepreneur David A. Butterfield, General Grenville M. Dodge, Mormon leader Brigham Young, the Gros Ventre leader Horse Capture, and fur trade giant Alexander Culbertson, who asked Lowell to transcribe his life story. All of these people played significant roles in the colonization of the West.

In the fall of 1865, Lowell accepted his first job: driving a freight wagon in the inaugural trip of the Butterfield Despatch, then launching a new route from Atchison, Kansas, to Denver. Like most citizens, Lowell was apparently unaware that Butterfields trail through the Smoky Hill Valley bisected the territory of the Cheyenne and Lakota Dog Soldiers, formidable defenders of native lands and cultures. The stage running ahead of Lowells wagon train was attacked at Monument Station by a party of warriors that probably included Charles Bent, the son of famous trader William Bent. Dog Soldiers also took all the livestock, mostly mules, from Lowells party of freight wagons but did not press a direct attack. As a result, the freight crew was marooned and on their own for thirty-one days, until the company drove in oxen to replace the mules. Lowell was fortunate to be in the vanguard of traffic crossing the Smoky Hill country, because the conflicts that ensued ignited a ten-year war for the Plains that culminated in the Battle of Little Big Horn during the summer of 1876.

Lowells passage across Kansas was just the first of his close calls, all of which he relates in a matter-of-fact fashion. Lowell was a careful observer and an unadorned but expressive writer. His manuscript reads like a highlights reel, carrying readers from Mormon settlements to mining camps, into crowded saloons where men fight over women, and through quiet mountain passes occupied only by eagles, antelope, and the sound of the wind. His cast of characters includes riverboat pilots, wolf hunters, and vigilantes, a heroic Indian chief, a scarred Spanish mustang, and a mystical mountain man. Sensing the epic nature of the era, Lowell sometimes quotes Shakespeare, Kipling, and Homer in order to more fully convey the dramas of frontier life.

Unlike many of his contemporaries, Lowell was aware that his experiences were part of a profound change, and many of his descriptions vividly bring people and events to life. He probably did not realize that his first-person account also expressed a perspective on those changes particular to white men of his status and generation. Indeed, some passages suggest that Lowell was driven by a belief in the tenets of Manifest Destiny, although he does not use that term. Thus, his lively narrative is at once history, literature, memoir, and cultural document. The publication of Lowells manuscript will be welcomed by all who seek to understand a pivotal moment in nineteenth-century America, not from the present, but as lived experience.

Castle McLaughlin, PhD

Curator, Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology,

Harvard University