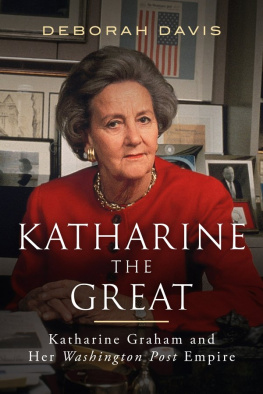

Katharine Graham

Katharine Graham is fondly remembered as the powerful, longtime publisher of the Washington Post. She died in 2001.

A LSO BY K ATHARINE G RAHAM

Personal History

Katharine Grahams Washington

Progress: A Personal Journey in Feminism

from Personal History

Katharine Graham

A Vintage Short

Vintage Books

A Division of Random House LLC

New York

Copyright 1997 by Katharine Graham

Introduction copyright 2014 by Katharine Weymouth

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies. Originally published in hardcover as part of Personal History in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, in 1997.

Vintage and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

The Cataloging-in-Publication Data for Personal History is available from the Library of Congress.

Cover design by Megan Wilson

Cover photograph by Linda Wheeler The Washington Post

Vintage eShort ISBN: 978-1-101-91147-1

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1_r1

Contents

Introduction

There are numerous women to whom we, as the modern generation, owe a debt of gratitude for breaking down the barriers to women in the workforce. Katharine Graham is one of them. She was also my grandmother.

Katharine Graham ran The Washington Post from 1963, when her husband passed away, until the mid to late 1980s. Although she rose to become one of the first female CEOs of a Fortune 500 company and one of the strongest and most able leaders of her generation, my grandmother was, as she writes, brought up to believe that our roles were to be wives and mothers, educated to think that we were put on earth to make men happy and comfortable and to do the same for our children.

It took her a long time to change those viewsand not only to change thembut to accept that she had an opportunity and even an obligation to smooth the path for other women.

At first, she accepted as a matter of course that the workplace was appropriately a mans world. Over time, her views evolved and she embraced her role as one of few female leaders in a very male world. This evolution came in part as she saw the feminist movement grow and learned from itbut perhaps far more from women at the Post who pushed her to challenge her views and to use her role as a woman leader to start to change the world. She did just that.

As I assumed the role my grandmother and uncle held before me, I sought to emulate the courage my grandmother showed in making tough decisionswhether in deciding to publish a controversial article or in business matters. I had the advantage my grandmother did not haveI was raised believing firmly that women can and do make great leaders. Today there are far more women in senior roles. But there are still too few. Our predecessors broke the barriers for women in the workplace and we must build on that.

Katharine Weymouth, Publisher, The Washington Post, 20082014

Progress: A Personal Journey in Feminism

W HEN IN 1969 I became publisher of the Washington Post as well as president of the company, my plate was fuller than ever. I had partly worked myself into the job but not, except for rare occasions, taken hold. I had acquired some sense of business but still relied on others more than most company presidents did. One article written about me that appeared fully five years after Id gone to work said, Mrs. Graham accepts her responsibilities much more often than she asserts her authority. That was true; I didnt always take charge or handle my relationships with people throughout the company in the coolest or best way. My expectations far exceeded my accomplishments. In fact, the years from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, rich and full as they were, were depressing for me in many ways.

I seemed to be carrying inadequacy as baggage. When I thought about my uncertainty and nervousness, a scene from the first musical comedy Id ever seen, The Vagabond King, kept recurring to me. There is a moment when the suddenly enthroned vagabond, appearing for the first time in royal robes, slowly and anxiously descends the great stairs, tensely eyeing on both sides the rows of archers with their drawn bows and inscrutable faces. I still felt like a pretender to the throne, very much on trial. I felt I was always taking an exam and would fail if I missed a single answer; a direct question about something like Newsweeks newsstand circulation would flummox me completely.

What most got in the way of my doing the kind of job I wanted to do was my insecurity. Partly this arose from my particular experience, but to the extent that it stemmed from the narrow way womens roles were defined, it was a trait shared by most women in my generation. We had been brought up to believe that our roles were to be wives and mothers, educated to think that we were put on earth to make men happy and comfortable and to do the same for our children.

I adopted the assumption of many of my generation that women were intellectually inferior to men, that we were not capable of governing, leading, managing anything but our homes and our children. Once married, we were confined to running houses, providing a smooth atmosphere, dealing with children, supporting our husbands. Pretty soon this kind of thinkingindeed, this kind of lifetook its toll: most of us became somehow inferior. We grew less able to keep up with what was happening in the world. In a group we remained largely silent, unable to participate in conversations and discussions. Unfortunately, this incapacity often produced in womenas it did in mea diffuse way of talking, an inability to be concise, a tendency to ramble, to start at the end and work backwards, to overexplain, to go on for too long, to apologize.

Women traditionally also have sufferedand many still dofrom an exaggerated desire to please, a syndrome so instilled in women of my generation that it inhibited my behavior for many years, and in ways still does. Although at the time I didnt realize what was happening, I was unable to make a decision that might displease those around me. For years, whatever directive I may have issued ended with the phrase if its all right with you. If I thought Id done anything to make someone unhappy, Id agonize. The end result of all this was that many of us, by middle age, arrived at the state we were trying most to avoid: we bored our husbands, who had done their fair share in helping reduce us to this condition, and they wandered off to younger, greener pastures.

When I first went to work, I was still handicapped with the old assumptions and was operating as though they were written in stone. When I started my job, I was inferior to the men with whom I was working. I had no business experience, no management experience, and little knowledge of the governmental, economic, political, or other matters with which we dealt. I truly felt like Samuel Johnsons description of a woman ministera woman preaching is like a dogs walking on his hinder legs. It is not done well; but you are surprised to find it done at all. Since I regarded myself as inferior, I failed to distinguish between, on the one hand, male condescension because I was a woman and, on the other hand, a valid view that the only reason I had my job was the good luck of my birth and the bad luck of my husbands death.