First published in Great Britain in 2018 by

PEN AND SWORD MILITARY

an imprint of

Pen and Sword Books Ltd

47 Church Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire S70 2AS

Copyright Paul Chrystal, 2018

ISBN 978 1 52672 885 2

eISBN 978 1 52672 886 9

Mobi ISBN 978 152672 887 6

The right of Paul Chrystal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Every reasonable effort has been made to trace copyright holders of material reproduced in this book, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publishers will be pleased to hear from them.

Pen & Sword Books Ltd incorporates the imprints of Pen & Sword

Archaeology, Atlas, Aviation, Battleground, Discovery, Family History, History, Maritime, Military,

Naval, Politics, Railways, Select, Social History, Transport, True Crime, Claymore Press, Frontline

Books, Leo Cooper, Praetorian Press, Remember When, Seaforth Publishing and Wharncliffe.

For a complete list of Pen and Sword titles please contact

Pen and Sword Books Limited

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

email:

website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

This book is part of the Pen & Sword series on historys architects of terror, books which are designed to describe the repellent nature and actions of the monsters who have stained world history down the years. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary defines monster in this context as a person of inhuman cruelty or wickedness and monstrous as deviating from the natural order, atrocious, horrible.

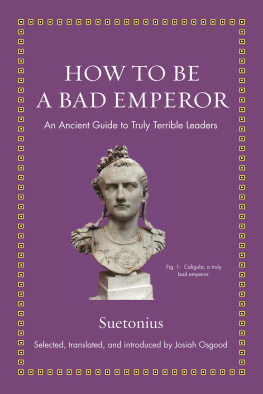

There are certainly a number of Roman emperors, and empresses, who merit the description monster, as this book will show; however, it is not the intention or purpose to offer yet another sensational and salacious catalogue of imperial deviants. Rather, the unnatural actions and atrocities of these emperors will be described, as far as possible, in the context of their times, the contemporary politics and societal norms. This is not an attempt to mitigate in any way their actions or to apologize for their bestial behaviour, simply to provide, as far as possible, balanced accounts given that some of the primary sources we rely onSuetoniuss Lives of the Caesars and the Historia Augusta for exampleare often infected with prejudice and a hankering after the sensationally tabloid. Moreover it is important that we never forget: Hitler and Stalin, monsters both, argued smugly that no one remembers the Ottoman governments industrial extermination of 1.5 million Armenians from April 1915 or the sack of Novgorod by Tsar Ivan IV The Formidable in 1570. Books such as this will ensure that we do remember and that we do not forget. Only by not forgetting do we have the slimmest of chances to learn from the abominations and their perpetrators and perhaps avert some future outrages. At the same time, we should be alert to the fact that the many victimsreal peoplesuffered torture, extreme fear and anxiety and, often, a painful death their only crime was being in the wrong place at the wrong time, and subjected to the whim of a deranged monster. It is important that the list of abominations described here does not become just thata list.

As with everything else, there were good and bad Roman emperors and empresses. The good, like Trajan (98117), Hadrian (117138), Antoninus Pius (138161), and Marcus Aurelius (161180) were largely civilized and civilizing. The bad, on the other hand, exhibited varying degrees of corruption, cruelty, depravity and insanity. It is sobering to remember that these brutes were responsible for governing the greatest civilization in the world despite their terror and brutality and massacres.

An explicit mural from Pompeiiunlikely to have raised many eyebrows.

Tiberius, Caligula, Nero, Domitian, Commodus, Caracalla, Elagabalus, Septimius Severus, Diocletian, Justinian, Theodora and the rest all had more bad days than good. Their exploits have, of course, been well documented since classical times but much of the coverage can only be called gratuitous, sensationalist or tabloid, published with an eye on sales rather than the facts. This book is based on primary sources and evidenceand it attempts to balance out, though not excuse, the shocking with any mitigating aspects in each of the lives.

Roman decadence contributed ultimately to its destruction, an 1836 painting by Thomas Cole.

Part of the reason for the sensationalism is, of course, the unreliability of the sources. Tacitusperhaps the most balanced and most contemporary, is nevertheless guilty of political bias against Nero and Domitian, for example. The biographer Suetonius in his twelve lives, was writing some time after his subjects lives and unashamedly spiced up his biographies with a selective approach to his own sources in order to satisfy his need for a racy, sensationalist account of each of the emperors. The Historia Augusta and its authors were even less troubled by the truth or the facts if they got in the way of a good storymore selectivity but padded out with false facts and fantasy. It is important as well to apply a certain degree of historical and social context. Death and sex were phenomena very differently regarded in the Roman world to how we see them today in the supposedly enlightened and liberal 21st century. Both are still taboo subjects with a capacity still to shock and embarrass, requiring hushed tones in their discussion: in ancient Rome they required nothing of the sort.

Warfare and conflict were an inextricable and constant part of Roman life, from the foundation of the state in 753 BC to the eventual fall of the Roman Empire some 1,200 years later. And so were the innumerable deaths which always went with the wars and battles. The belligerence of the state was always integral to Roman political life: Roman bellicosity shaped their economy and defined their society. Josephus, writing in the 1st century AD, stated that the Roman people emerged from the womb carrying weapons. Centuries later, F. E. Adcock echoed these words when he said a Roman was half a soldier from the start, and he would endure a discipline which soon produced the other half.

Romes obsession with war stretched over her 1,200 years of history and saw Roman armies fighting in and garrisoning the full extent of her territories, from Parthia in the east (modern-day Iran) to Africa (Tunisia) and Aegyptus in the south (Egypt) and to Britannia in the cold northwest. There were few years in which there was no conflict: each summer, when the campaigning season began, an army was levied, consuls or dictators took command, and battles were fought, before the army was disbanded at the close of the fighting year. Each summer, news would filter back to Roman and Italian families that husband, father, brother or cousin was not coming home. Death then through war was an accepted part of family life.