Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

Young Heroes of the Soviet Union is a work of nonfiction. Some names and identifying details have been changed.

Copyright 2020 by Alex Halberstadt

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

R ANDOM H OUSE and the H OUSE colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to Margarita Novgorodova for permission to reprint Northern Elegies by Anna Akhmatova. Reprinted by permission of Margarita Novgorodova.

Photo credits are located on .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

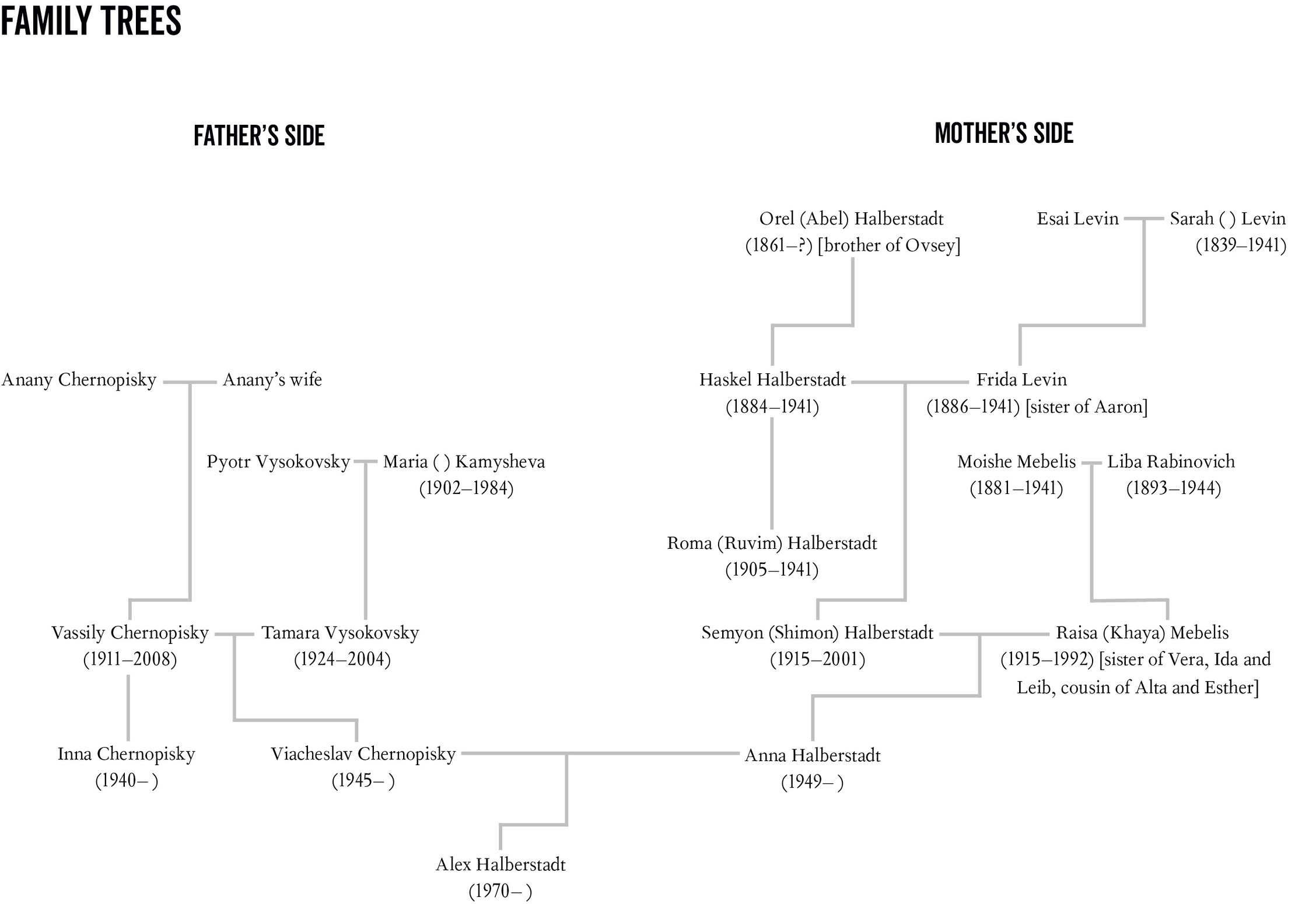

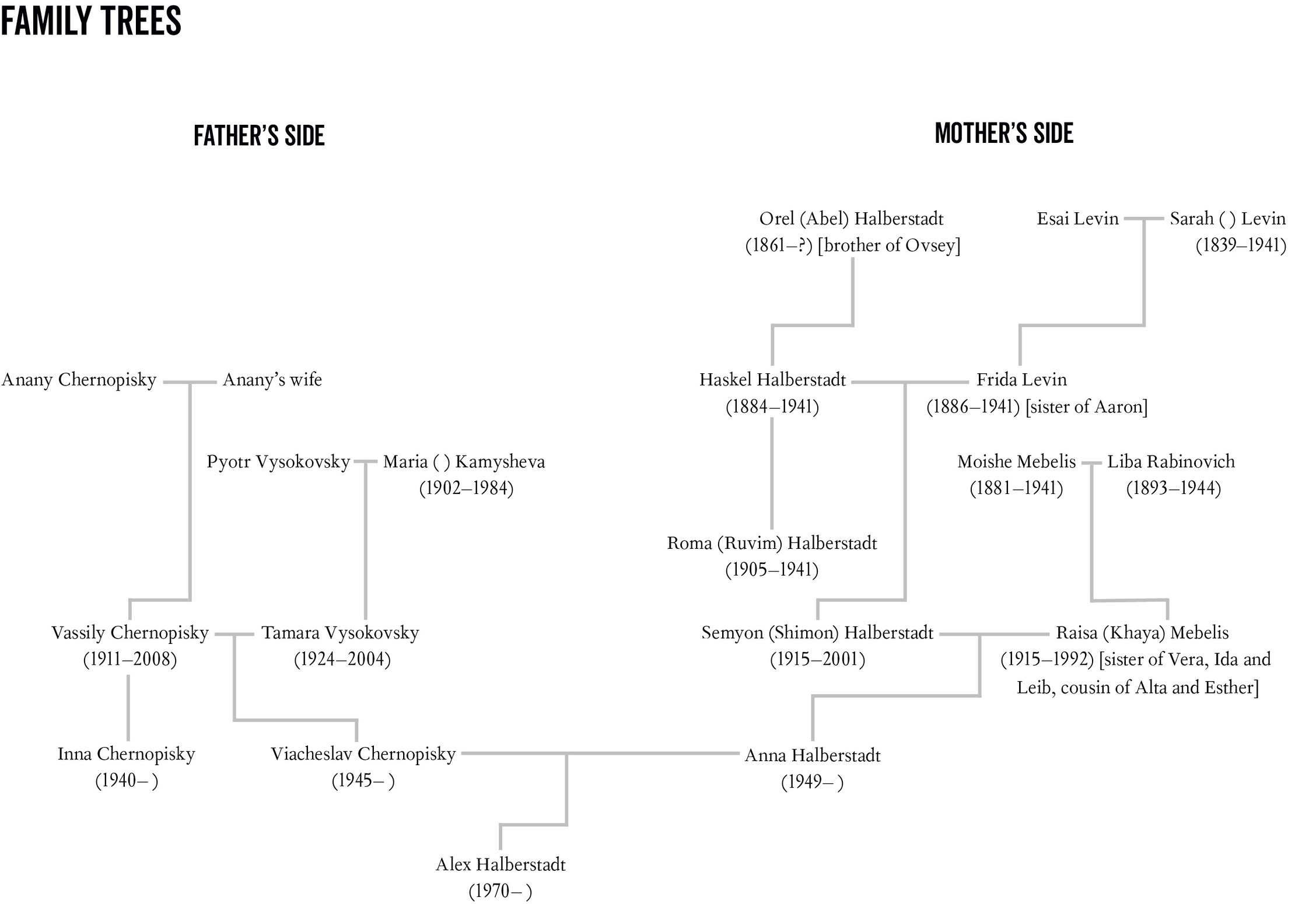

Names: Halberstadt, Alex, author.

Title: Young heroes of the Soviet Union: a memoir and a reckoning / by Alex Halberstadt.

Description: First edition. | New York : Random House, [2020]

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019658 | ISBN 9781400067060 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593133071 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Halberstadt, AlexTravelRussia (Federation) | Jews, SovietUnited StatesBiography. | Halberstadt, AlexChildhood and youth. | JewsSoviet UnionBiography.

Classification: LCC DS134.93.H35 A3 2020 | DDC 305.892/4047092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019658

Ebook ISBN9780593133071

randomhousebooks.com

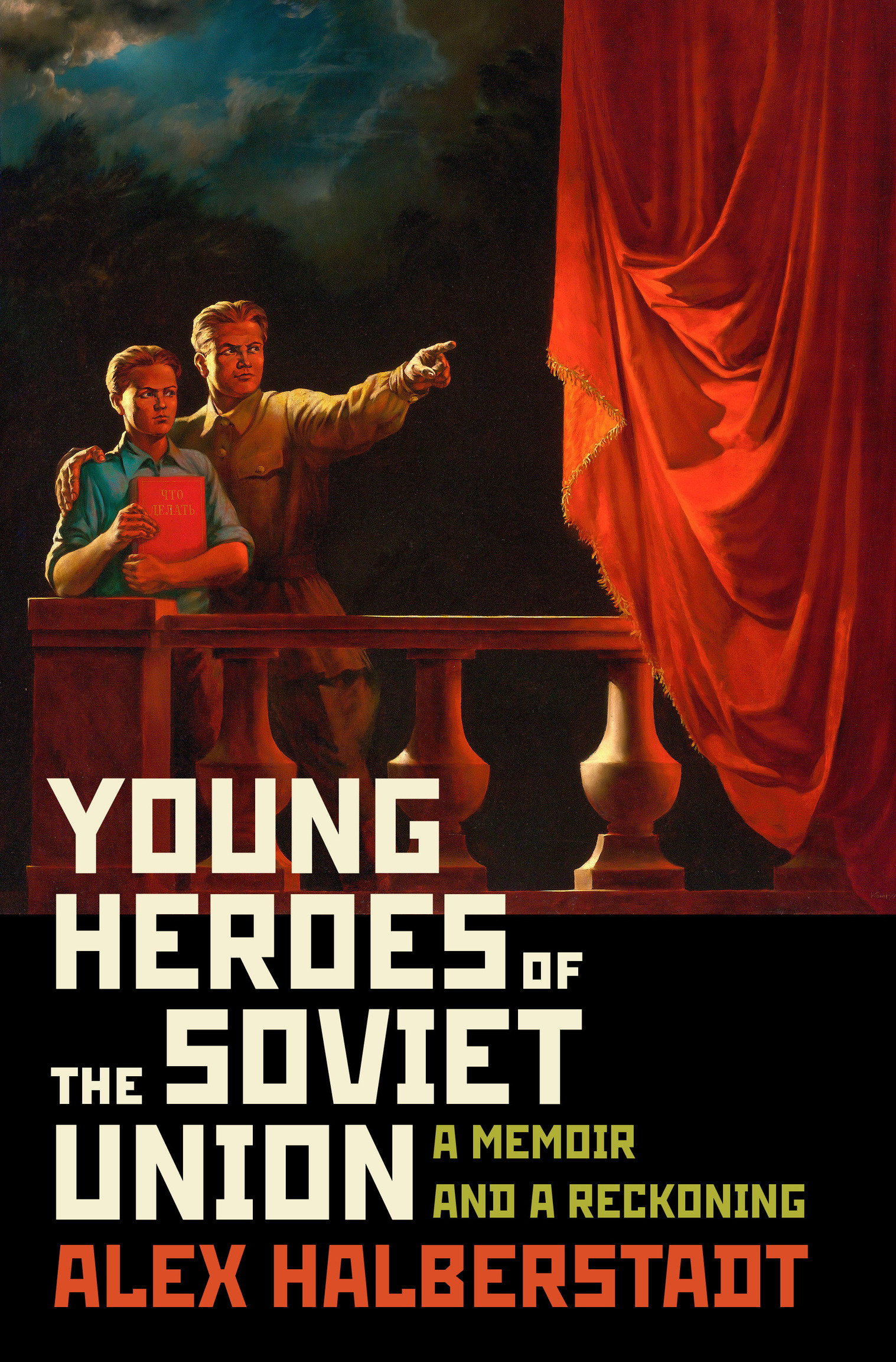

Cover art: Komar and Melamid, What Is to Be Done? (from the Nostalgic Socialist Realism series), 1983; photograph courtesy of Sothebys

v5.4

ep

Contents

You who do not remember

passage from the other world

I tell you I could speak again: whatever

returns from oblivion returns

to find a voice.

Louise Glck, The Wild Iris

When we are confounded or lost, stories have the power to lend meaning to our disorder, and not long ago I found just such a story in the pages of a science magazine. Or maybe it found me. It described how a team of researchers at Emory University in Atlanta had blown air scented with a chemical that smells like cherry blossoms into a cage of baby mice, then administered an electric shock to the animals feet. Eventually, the mice learned to associate the scent of cherry blossoms with pain and trembled with fear whenever they smelled it. The surprising part, though, came after they had babies of their own. When exposed to the scent, the second generation also trembled, though they had never been shocked. Their bodies had changed, too. They were born with more smell-sensing neurons in their noses, while the structures in their brains that receive signals from these neurons had grown larger.

Puzzled by these results, the researchers worried that they were witnessing an anomaly. And so they made sure that the next generation of micethe grandchildrenhad no contact with their parents whatsoever; in fact, they were conceived using in vitro fertilization in a laboratory on the other side of campus. But these mice also trembled at the cherry-blossom scent and demonstrated identical brain changes. The experiment appeared to show that one generations trauma was passed on physiologically to children and grandchildreneven in the absence of contact. What the researchers couldnt explain was how or why this was happening.

After these findings were published in 2013, studies of human subjects confirmed that the Emory researchers were on to something: Markers attached to certain genes are influenced by ones environment. A study conducted at Mount Sinai Hospital in New York found that children of Holocaust survivors showed changes to the genes that determined how they responded to stresschanges identical to those found in their parents. Another study showed that pregnant mothers who were near the World Trade Center during the attacks of September 11, 2001, gave birth to children with similar alterations to their genes. The children in these studies showed a propensity for post-traumatic stress disorder that had no explanation rooted in their own lives, a condition that one researcher described as a tendency to feel unsafe in a safe environment. Most theories attempting to explain these findings rely on the relatively new field of epigeneticsthe study of changes in gene expression rather than the genetic code itselfthough aspects of the theories remain poorly understood and controversial.

I first read about these studies at a particularly unsettled time in my life, when I was trying to piece together my own familys history. The studies seemed to speak to something I was coming to believe, something I wanted to believe because I sensed it so acutelythat the past lives on not only in our memories but in every cell of our bodies. It was a deterministic notion to be sure, but it helped explain certain recurrent and mystifying experiences shared by the past three generations of my family: ruptured relationships, presentiments of disaster, clinical depression and anxiety, chronic sleep disturbances, a proclivity for keeping secrets and an ever-present sense of danger.

For some reason, I kept returning to the study of the mice at Emory. Eventually, I realized that what drew me to it were not only the provocative findings but its potency as a metaphor. Could it be that we, too, were trembling at stimuli we could neither identify nor remember, stimuli that had their origins in the decades prior to our births? It was unnerving to imagine that the past could be living through us without our consent or knowledge. But if it were true, it also meant that with time and effort these long-gone stimuli could be named and, at long last, acknowledged.

THERE WERE ALWAYS dogs barking in my dreams, my mother said. In the bad ones, anyway. They began the year I turned nine, while my mother, her parents, and I were making our nomadic way from Moscow to New York. They happened in budget hotel rooms in Austria and Italy and Manhattan and later in a succession of apartments in the wastes of Queens.

Most of the dreams werent particularly memorable, but there was a recurring one that stood out. It takes place in Stepanovskoye, a village near Moscow where, in summers, my family rented the front part of a blue clapboard house with green shutters. In the dream it is dusk, and I stand at the gate in the picket fence in front of the house, wanting badly to go inside. My parents are in the house, and I can smell the wood smoke from my great-grandmothers stove. But the landladys bulldog has gotten off the chain and is barking on the other side of the fence, constricting my throat with fear. I cant decide what to do, but it is getting dark and I need to get home, so eventually I throw open the gate and lunge for the door, and the bulldog lunges after me, snarling just over my shoulder. Thats when Id wake, my pulse juddering, my pillow damp with sweat. Right away the events of the dream seemed to break apart, to turn to dust even as I reached out for them. Sometimes, if my mother was asleep, I snuck into the kitchen, took a knife out of a drawer and kept it under my pillow until morning, lying in bed uneasily and watching the cold light through the curtains. The dream has refused to go away, even all these years later.