Lewis Hine

Photographer of Americans at Work

SERIES CONSULTANT

Jeffrey W. Allison

Paul Mellon Collection

Educator, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts

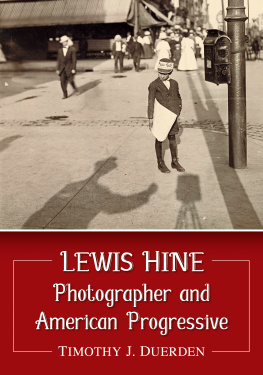

Cover Photos:

Powerhouse Mechanic (Lewis Wiekes Hie);

Row of Tenement Houses, 260 to 268 Elizabeth St. (Lewis Wiekes Hine).

First published by 2009 M.E. Sharpe.Inc

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2009 by Taylor & Francis. All rights reserved.

Series created by Kid Graphica, LLC

Series designed by Gilda Hannah

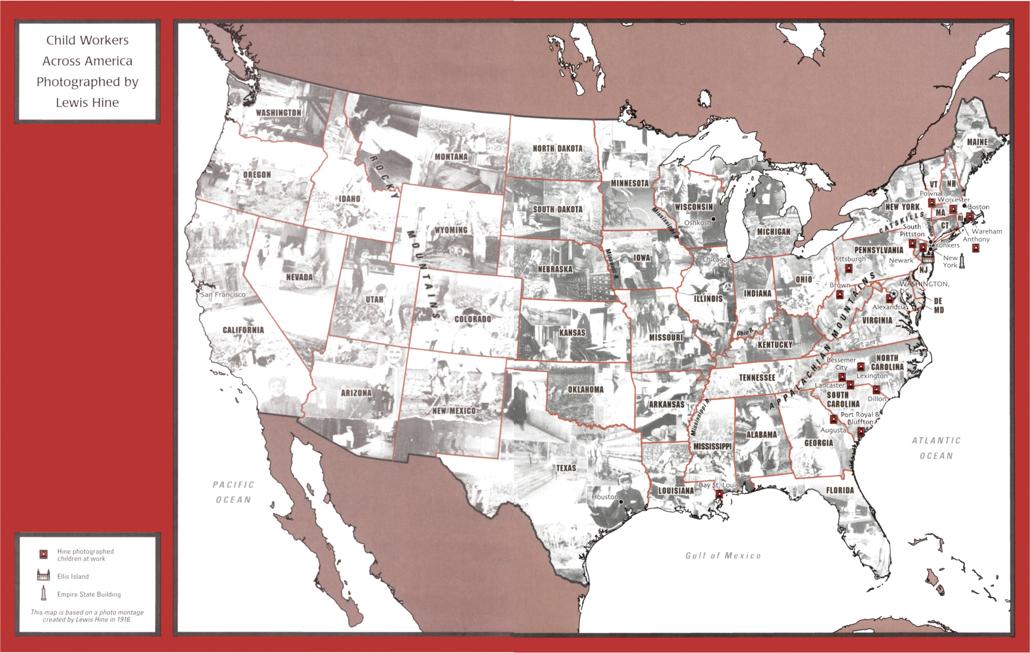

Map: Mapping Specialists Limited

No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notices

No responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to persons or property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any use of operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the material herein.

Practitioners and researchers must always rely on their own experience and knowledge in evaluating and using any information, methods, compounds, or experiments described herein. In using such information or methods they should be mindful of their own safety and the safety of others, including parties for whom they have a professional responsibility.

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Worth, Richard.

Lewis Hine: photographer of Americans at work / Richard Worth.

p. cm. (Show me America)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-7656-8153-9 (hardcover: alk. paper)

1. Hine, Lewis Wiekes, 1874-1940Juvenile literature. 2. Photographers

United StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 3. Child laborUnited

StatesHistoryPictorial worksJuvenile literature. 4. Documentary

photographyUnited StatesHistoryJuvenile literature. 5. United States

Social conditionsPictorial worksJuvenile literature. I. Title.

TR140.H52W67 2008

770.92dc22

[B]

2008004426

ISBN 978-0-76568-153-9 (hbk)

By the Children of America in Mines and Factories and Workshops Assembled

Lewis Wiekes Hies documentary photography helped promote the cause of the National Child Labor Committee, which published this declaration in 1913:

WHEREAS, We, Children of America, are declared to have been born free and equal, and

WHEREAS, We are yet in bondage in this land of the free; are forced to toil the long day or the long night, with no control over the conditions of labor, as to health or safety or hours or wages, and with no right to the rewards of our service, therefore be it

RESOLVED, I That childhood is endowed with certain inherent and inalienable rights, among which are freedom from toil for daily bread; the right to play and to dream; the right to the normal sleep of the night season; the right to an education, that we may have equality of opportunity for developing all that there is in us of mind and heart.

RESOLVED, II That we declare ourselves to be helpless and dependent; that we are and of right ought to be dependent, and that we hereby present the appeal of our helplessness that we may be protected in the enjoyment of the rights of childhood.

RESOLVED, III That we demand the restoration of our rights by the abolition of child labor in America.

Lewis Hine was eleven years old when this portrait was made.

The great social peril is darkness and ignorance.

Lewis Hine

In 1910, a shy, slim photographer stood in front of a large audience which sat in hushed silence. They were stunned by the images that he had just shown them. The photographer had used a magic lanternthe forerunner of the slide projectorto project photographs that had been reproduced on glass plates onto a screen. Shocking images of childrenAmericas childrenengaged in backbreaking labor filled the darkened room. Over 2 million children under the age of sixteen worked twelve to fourteen hours a day in similar conditions.

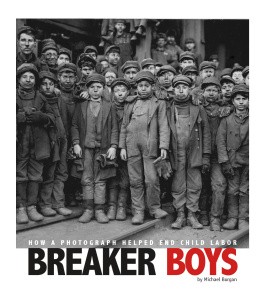

One of these children was a little girl named Sadie, who stood in front of a giant spinning machine, working in a mill where the heat and the dust made breathing very difficult. Others were boys who worked deep inside the Pennsylvania coal mines as trappers, opening the doors from the mines to let out the cars filled with coal. Day after day, they breathed in black coal dust, which coated their lungs and their faces with soot.

Some younger children were breaker boys, sitting outside the mines over coal chutes and taking out pieces of stone that could not be sold because they would not burn. Their fingers were constantly cut by the coal flowing down the shoot. While I was there, the photographer said, two breaker boys fell or were carried into the coal chute, where they were smothered to death.

Some children worked in the tenement buildings of large cities, such as New York and Chicago. There, entire families worked together in poorly lit apartments with no fresh air, making artificial flowers or sewing lace. They earned about $ 1 a day, six days a week, often working until late in the evening. The lace or the flowers they made were sold to affluent people, such as the ones who sat in the audience listening to the photographers lecture and looking at his pictures. They seemed to have little or no idea of the working conditions that they saw on the screen.

The great social peril is darkness and ignorance, the photographer wrote. His goal was to educate his audience and increase their understanding of childrens working conditions. Mostly, he let the subjects speak for themselves as they looked directly into his camera and communicated their stories. But these were not sad victims. They were proud children whose voices were heard through the pictures and descriptions provided by the soft-spoken photographer.

Immigrant families made lace in their dreary tenement apartments for $1 a day.

The United States was in the midst of an industrial revolution, which had begun during the nineteenth century. Factories had sprung up across the country. Deep mines had been dug to provide large supplies of coal that could fuel the new manufacturing plants, and cities had grown to house the hundreds of thousands of workers needed for Americas industries. While some entrepreneurs became rich during industrialization, many other people worked for low wages and long hours in the mines, the factories, or in their own homes. Adults and children worked side by side to earn enough to feed their families. There were no laws protecting the health and safety of workers and no laws preventing child labor.