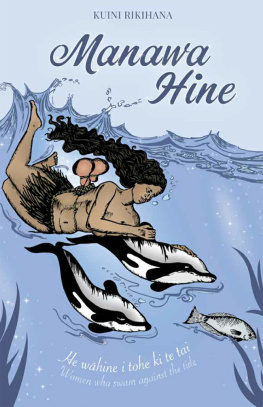

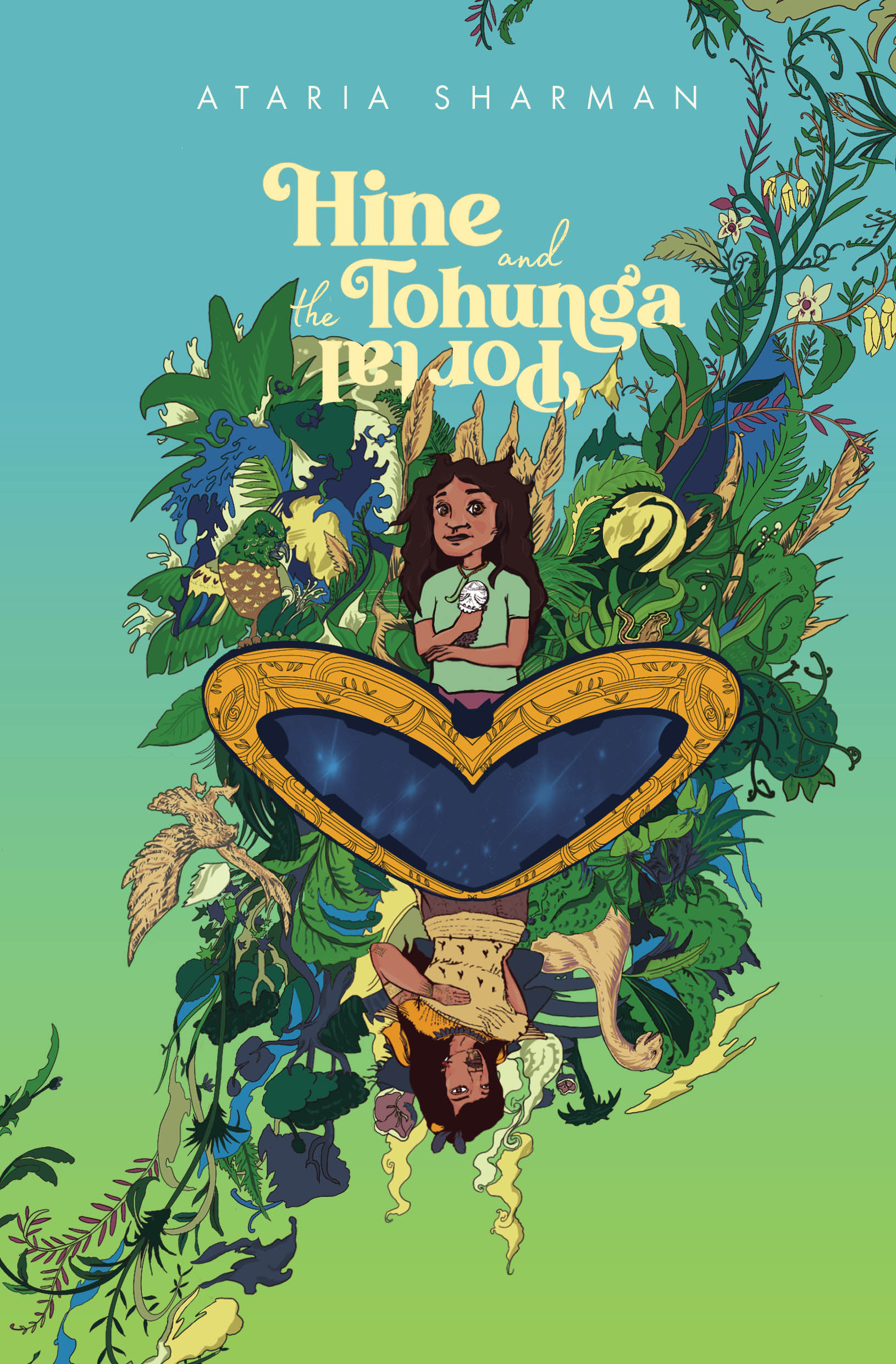

First published in 2021 by Huia Publishers

39 Pipitea Street, PO Box 12280

Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand

www.huia.co.nz

ISBN 978-1-77550-634-8 (print)

ISBN 978-1-77550-643-0 (ebook)

Copyright Ataria Sharman 2021

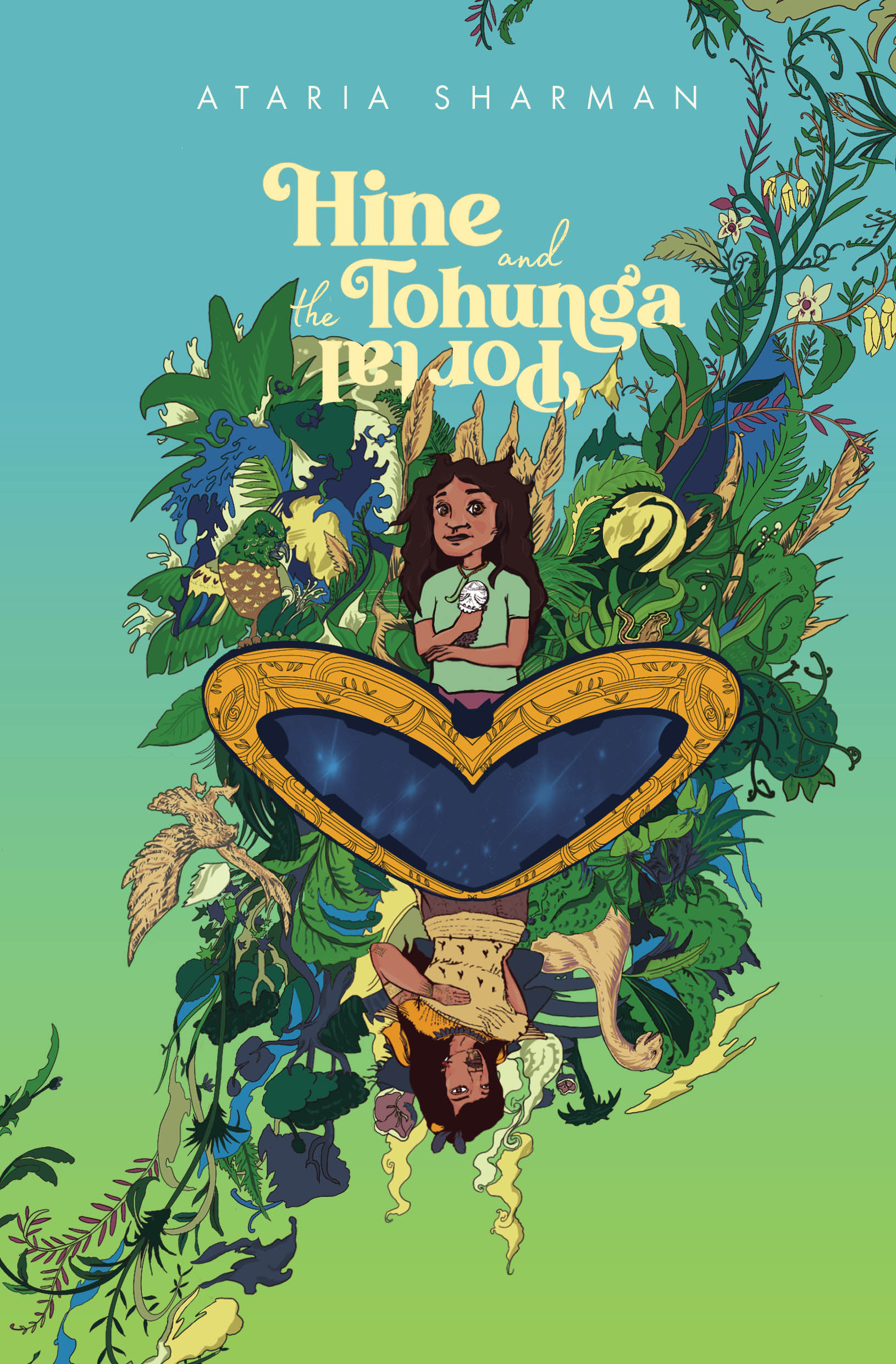

Cover illustration copyright Reweti Arapere 2021

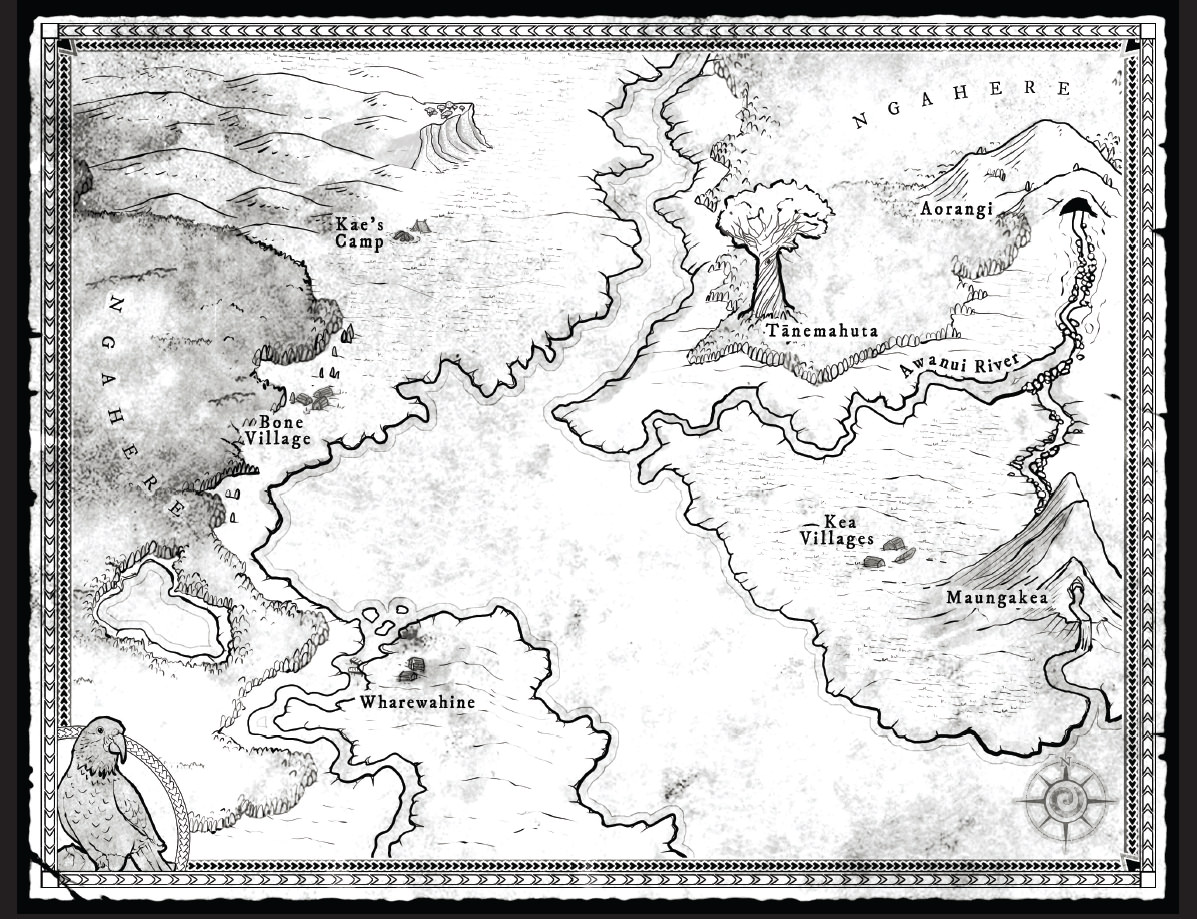

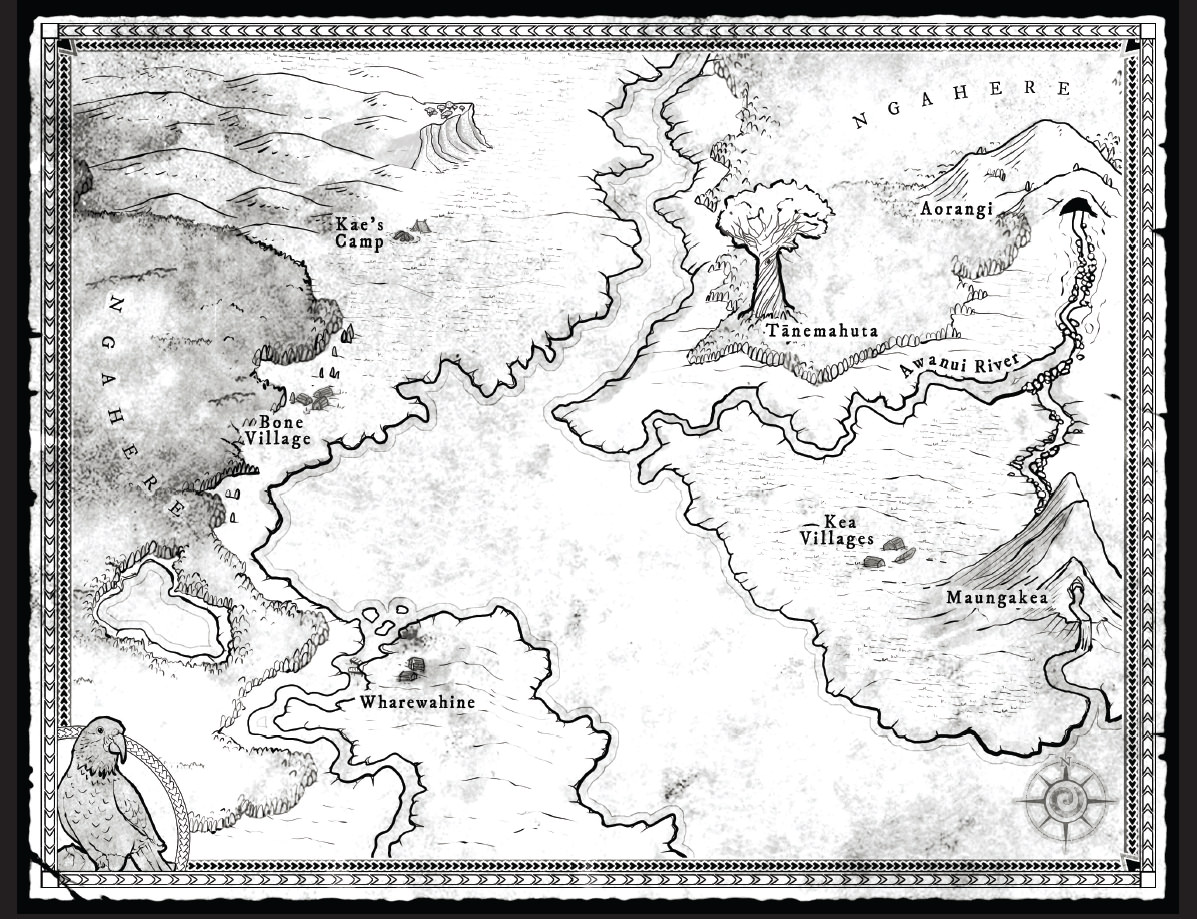

Map illustration: Original by RenflowerGrapx / Maria Gandolfo;

revised by BMR Williams

This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without the prior permission of the publisher.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

Published with the support of the

Ebook conversion 2021 by meBooks

E tika ana kia mihi au ki ng tipuna kuia nei ki a

Papatnuku, Hineahuone, Hinettama, Hineteiwaiwa tae noa mai ki a Kanarahi, Rangipikitia me Herapia.

Ki taku irmutu hoki ki a Hhepa Monaghan

CONTENTS

I t started off like any other day. Hine swept the duvet off her feet and pushed onto the cold wooden floor, which creaked under her foot. At night, going to the wharepaku, she had to tiptoe, or the floor would croak like a toad in a fairytale and wake her parents.

She imagined a slimy toad now on the planked wooden floor of her bedroom, and was thankful that they dont live in Aotearoa, the land of the long white cloud.

Hine looked out her streaked and blurred window and sighed. The land of the long white cloud doesnt sound right. Its always raining. It should be the land of the long black rain cloud.

After breakfast, she and her brother, Hhepa, set off to school, huddled under a faded, holey umbrella. On the front step of the house, Hine pressed her hands against the straps of her backpack. She yanked up her turquoise overalls and felt the weight of the bag rest on her shoulders.

The orange door closed loudly behind them. Hine looked back at the old wooden state house, the yellow paint cracking and lifting like bark. A fat raindrop hit her on her arm as she looked down at her worn shoes. The pooled water in the cracks of pavement leeched into her white socks.

She was proud of her bright purple backpack from Kmart. Hhepa had one too but his was black. Sometimes the other kids at kura would tell her that because they were so short she and Hhepa looked like two backpacks walking themselves along the road.

Hine held her hand outside the umbrella, but it stayed dry.

Woohoo! The rain has stopped, exclaimed Hhepa as he took off, striding forward to get ahead of his sister.

Hine looked at her brother and all she could see of him was a black tuft of his curls. She tossed a plait behind her back.

Skipping ahead, Hhepa began practising his waiata from kapa haka, He hnore, he korria.

Hine covered her ears. Its annoying having a little brother. Why couldnt I have a little sister instead? Named Marama. With a cute little face. She smiled to herself, and paused.

He hnore, he korria.

Snapped out of her reverie, Hine commented, Hhepa, youre way off-key.

Hhepa poked out his tongue and sprinted towards the yellow school gates, shouting, Do you think I caaare what you say, Hine?

Ugh. She rolled her eyes and watched him run across the black asphalt and into his classrom.

At kura, Hine and Hhepa had kapa haka with their kaiako Matua Hone. Hine thought he was crack-up because he would always turn up late to kapa haka practice, his hair messy and flopping over his eyes.

He had sweat dripping down his brow today, and his round face was beaming as he carried his guitar with gusto into the school hall. Had to run to get here on time, tamariki m! Had a staff meeting. But the glint in his eye told Hine that he wasnt late because of a staff meeting.

Hine had a gift for picking up on little hints like that. The look in somebodys eyes, the movement of the body, the flick of the hair. Sometimes she thought maybe she might be a mind-reader. Especially of adults. Adults always think children dont know when they are lying.

I wonder what would happen if they realised I knewmaybe its a superpower? She was hopeful as she stared out the halls window. The branches of a tree were whipping across the glass.

Hine thought hard for a moment. She had a strong suspicion that Matua Hone was late because he had been visiting the newest kaiako: Whaea Moana.

Whaea Moana was tall, slender and muscled, with wavy long brown hair and a pretty face. She was also fluent in te reo.

For all of those reasons, Whaea was the most amazing person Hine had ever known. Hine couldnt speak te reo, and her parents didnt too much either, just a few words here and there. She wasnt sure why her family didnt speak it at home, like the other kids families did.

Hine joined Nghina and Miriama in the second row. They were gossiping about Matua Hone always annoying Whaea Moana. Asking her if she wanted help with her books. With her classroom. With her reo. They mimicked Whaea Moana with their voices and used their hands to shoo Matua Hone away.

Nghina put her hands on her waist. I can carry my own books, thank you, Hone.

Miriama flicked her hair. I am a qualified teacher, Hone. I dont need help setting up my akomanga.

Hine rolled her eyes. My reo is fine, thank you, Matua. Go annoy one of the other kaiako.

They snickered and covered their mouths with their hands. Matua Hone sang the opening line of the waiata, and Hine tried to ignore the looks Nghina and Miriama were giving her. Silly Matua Hone. Her mm always said, Watch out for those men, Hine. They are silly. Without a woman to keep them in line, pai kare! A whole bunch of headless chickens running around thats what they would be. A bunch of chickens!

Hines mum knelt down to tidy the pukapuka lying across the classroom as the rest of Hines kapa haka friends filed in. She was a teaching assistant at the school, and Hines dad was the school caretaker. They worked hard, and long hours, but didnt earn too much. Hine didnt mind, though. She liked their old house. She didnt need all the fancy things that some of the other kids had.

Hhepa, on the other hand, was always complaining. He wanted an iPhone, an iPad, a PlayStation 4, a laptop. But they just couldnt afford those things.

Hines mum yelled out Trevor! She tapped the man walking past the doorway on the shoulder and pointed to the rubbish bins down the hall. He smiled at her, his cheeks red, and walked off. The back of his work clothes was covered in stains.

Hine had spent her life watching her mm boss Pp around.

Trevor, honey, can you please do this?

Trevor, honey, this needs fixing.

Trevor, honey, take the rubbish out.

Hine couldnt understand why her pp still needed to be told after all these years to do things like empty the rubbish. Doesnt he notice when the bin is full? And doesnt Mum get sick of reminding him?

Next page