Table of Contents

To Joe and Pam, Guy and Amy,

Nell and Iago,

with love

Every story of investigation and of conjecture tells us something we have always been close to knowing.

UMBERTO ECO

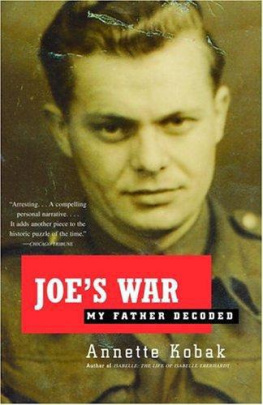

Acclaim for Annette Kobaks

JOES WAR

Kobak is a smart, even elegant writer, capable of pithy observations that jump off the page.

The Washington Post

[Kobak] points out that Australias Aborigines believe that our stories are what we are here for. By finally learning her fathers story, she recognizes, her own becomes much richer.

Newsweek

Kobaks thrilling race to discovery carries the reader along. Like her, we cant wait to know what happened next, and why; like her we are filled with hopeless fury as politicians abolish lives and nations to ingratiate themselves with other politicians. We applaud breathlessly as Joe slips one trap after another, and stand fascinated as chance meetings lead to serendipitous revelations.... Annette Kobak both reveals a Europe we never knew and points out the importance of knowing it.

The Independent (London)

This moving book finally tells the story that Kobak never heard in her childhood. It is the story of one Central European mans war, and a success story about tact, love and trust slowly putting right the damage done by past trauma. But it is also, because of the nature of his experiences and the subtlety and intelligence with which she approaches them, the story of the twentieth century.

The Times Literary Supplement (London)

A fascinating and enjoyable book. Eminently readable, it rambles engagingly and instructively through many spheres, private and public, leaving one with haunting reflections.

The Sunday Times (London)

As well as being a meditation on the way that stories which once seemed frozen behind the iron curtain are now thawing back to life, Joes War is also a frank account of the impossibility of ever fully realising that your parents once knew a time that did not include you.

The Guardian (London)

Heart-stoppingly exciting.... Joe Kobaks tale of escape, engagingly told in his own words by his daughter, would stand alone very well as a war memoir. It is gripping and studded with humour.... Its description of the chaos is reminiscent of the Dunkirk scenes in Ian McEwans Atonement. But this war memoir is only one strand of... this complex and unusual book.

The Sunday Telegraph (London)

This is one of the most unusual books on the Second World War to be published in recent years.... This is a remarkable story well told.

Contemporary Review

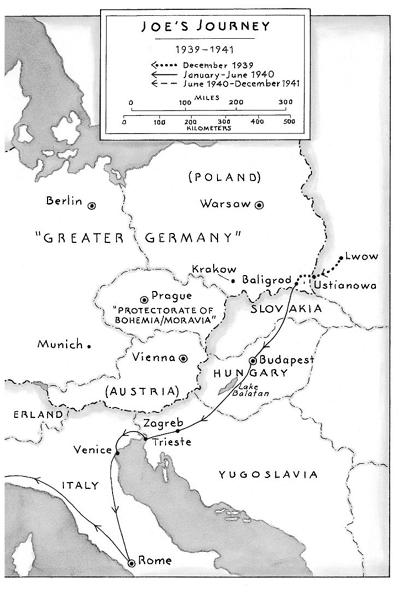

AUTHORS NOTE

This is not a war story in the usual sense. Its an excursion into the Second World War on a very personal mission, to try to make sense of my fathers silences. Even the discoveries Ive made on that score have been small scale, although one of them opens up a new perspective on Polish involvement in the war, and widens out into a broader panorama of secrecy. My father had no particularly heroic role in the war, though having put the pieces together now, I know he was brave in quietly resourceful ways: he was brave in protecting his family by a lifetime of silence, for a start. And he was brave as a young man in not being felled by successive war blows randomly striking him. It was an uninvited bravery, hed be the first to say. Indeed, what I love about his story, and what I sensed even before I knew it, was that it was such a foot soldiers story, an unwilling foot soldiers story, one who never intended to have anything to do with war at all but was quietly minding his own business in Lwow in Poland when war decided to change his plans. His silence after the war, which I grew up with, was not so much a question of protecting dramatic secrets, though secrets there were, as trying to manage his fear and confusion. Heand my mother by osmosis, although she knew nothing of his story eitherdidnt want to pass on this fear and confusion to me, but of course by bottling it up and laying it down in the psychic cellar he outlined its contours to me.

His story was a sliver of war, like the stories of so many others, particularly from middle Europe, stunned as they were by the successive blows of Nazism and Stalinism and the cold war. But there was also some form to it: I sensed it had some meaning, if only I could put it together. When I finally did so, I found it told me most of what I needed to know about the nature of any war, and a lot that I didnt know about the origins of this one. Which is why I want to add it to the bookshelves, as a small counterweight to the deplorable fact that not only did dictators like Hitler and Stalin cause unprecedented trauma in millions of lives, which has knocked on down the generations, but that history now grants these two dictators far more shelf space than it does to people who brought their whole humanity and intelligence to bear on trying to stop such horrors. This book is peopled with such men and women, and with others who were simply caught off balance by the monster from outside, as Milan Kundera called twentieth-century history, and did their best in the circumstances, like my father.

If my father, Joe, had not been a very young soldier, he might not still be alive nowa youthful eighty-three-year-oldand I would never have known what had happened to him before he came to England, and why he was so enigmatic. There is barely a trace of him in official records, and no one left who knew him from that time. So I also offer this in the hope that it may stand in for others who were not so lucky, and that it may throw light on their behalf, too, on some lesser known landscapes and legacies of the war.

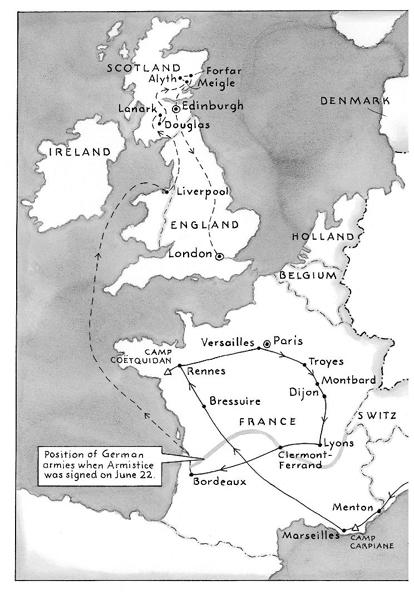

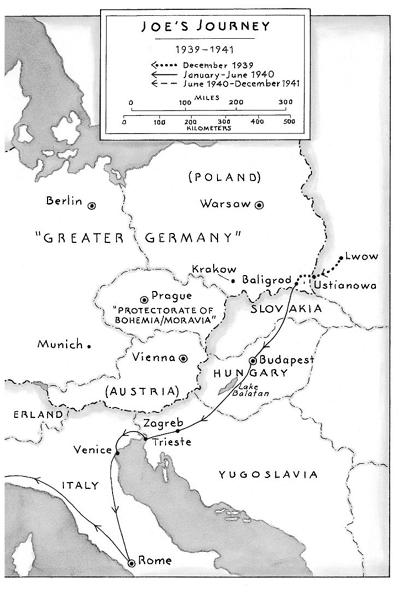

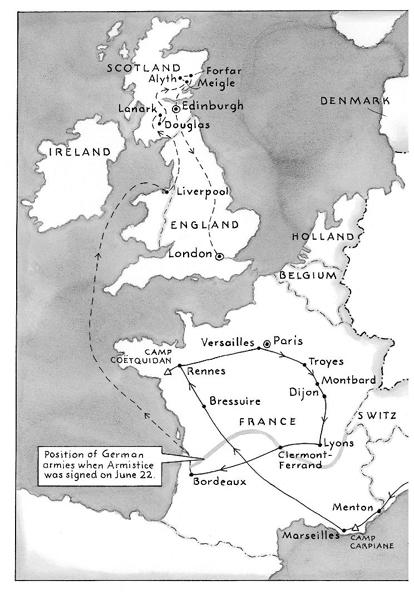

Map of Joes Journey

ONE

ANOTHER COUNTRY The parents unconsciously passed their unmastered personal history on to their child at a tender age, often simply by way of glances. ALICE MILLER

THE SILENT SLAV

It didnt occur to me to ask my father as I grew up why he had nothing from his past before the warno pictures of himself when young, no family photographs, no mementos of any kind. He was a man without a past, and I failed to notice. Since I grew up alongside the void, it seemed natural to me, as natural as the way his eyes oscillated continuously, or the way he slept with a hammer under his pillow.

Throughout my time at home in southeast Londonfirst in a flat in Crystal Palace and then in a small, semidetached house in a drab suburb called Anerleymy father was often taciturn, irritable and cowled with gloom. His whole manner discouraged questions about himself, even if Id been disposed to ask them, which, like most children, I wasnt. I was also my parents only child, and, like most only children, took on the adults coloring more than usual, being outnumbered. If the grown-ups werent talking about something, I wasnt talking about it either.

The only facts I knew about my father as I grew up were that hed been a soldier with the Polish army in the war and had ended up in London, where hed met my English motherwho was in the womens air force at the timeplaying table tennis. At the end of the war hed taken a job as a watchmaker at Bravingtons in Kings Cross, and at the same time studied in the evenings for a physics diploma somewhere in London. I thought he was Polish, because hed been in the Polish army and had three Polish friends from those days. It wasnt until much later that I learned he was born in Czechoslovakia, so was technically Czechoslovak. By the time I began asking these questions, he was anyway naturalized British; and by the time I really started to ask him questions, he had emigrated to Australia.

Next page