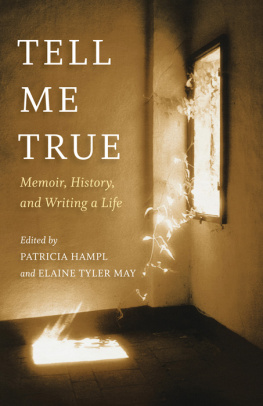

Tell Me True

TELL

ME

TRUE

Memoir, History,

and Writing a Life

Edited by

PATRICIA HAMPL

and ELAINE TYLER MAY

Borealis Books is an imprint of the Minnesota Historical Society Press.

www.borealisbooks.org

Selection of essays 2008 by the Minnesota Historical Society. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Page 231 constitutes an extension of this copyright page. For information, write to Borealis Books, 345 Kellogg Blvd. W., St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

The Minnesota Historical Society Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

Manufactured in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

International Standard Book Number

ISBN 13: 978-0-87351-630-3

ISBN 10: 0-87351-630-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tell me true : memoir, history, and writing a life / edited by Patricia Hampl and Elaine Tyler May.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-87351-630-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-87351-630-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-87351-703-4

1. Autobiography. 2. Biography as a literary form. 3. History in literature. 4. Truth in literature I. Hampl, Patricia. II. May, Elaine Tyler.

CT25.T448 2009

809'.93592dc22

2008016607

Contents

P ATRICIA H AMPL & E LAINE T YLER M AY

F ENTON J OHNSON

A NNETTE K OBAK

H ELEN E PSTEIN

J UNE C ROSS

M ICHAEL P ATRICK M AC D ONALD

E LAINE T YLER M AY

A LICE K APLAN

M ATT B ECKER

P ATRICIA H AMPL

C HERI R EGISTER

C ARLOS E IRE

S AMUEL G. F REEDMAN

A NDR A CIMAN

D. J. W ALDIE

Tell Me True

PATRICIA HAMPL & ELAINE TYLER MAY

Introduction

So whats the story? That homely question isnt seeking mere entertainment, certainly not ction. Its asking for the truth. Or at least, a reasonable rendition of facts, reliable strands of information. But once this search produces a narrative, truth reveals its essential malleability in the face of storytelling. Writers of nonction face this conundrum daily. Its an occupational hazardand an occupational fascination.

Memoir and history regard each other across a wide divide. In effect, theyre goalposts marking the extremes of nonction. The turf that separates themand of course connects themis the vast playing eld of memory. Though both forms are narrative and require the storytelling arts, they reverse each othermemoir being personal history, while history offers a kind of public memoir. A tantalizing gray area exists where memory intersects with history, where the necessities of narrative collide with mundane facts. The record always retains blank spaceswhether the record emerges from archival sources or from personal memory. Onto that blank space writers in both genres bring the remnants of the past they select in telling their stories.

This space is the uncomfortable location where the historian and the memoirist do the work of interpretation and imagination. History properly claims the authority of documentary record. Memoir, especially in recent times, angles forward with strong claims for the individual voice. History charts the big picture, memoir offers the intimate portrait. Like opposing teams on the same eld they seemand sometimes arecharging against each other.

And yet.

When a little girls diary, faithfully kept in the threatened secrecy of her hidden life, stands as the greatest testamentary document to the worst recorded events of the twentieth centurywe know postmodern readers, not to mention postmodern writers, have narrowed the space between private and public, between the writing of history and the accounting of a personal life. Authority has shifted from facts to voice. Not that one cancels the other. Nor is this shift simply bad news or good news, but a very complicated story in itself. That storyabout the record of history and the voice of memoir, about the documents of an individual life and the articulation of a shared pastforms the puzzle the essayists in this collection attempt to address.

The writers herehistorians, journalists, poets, and ction writersare also memoirists. Theyweare caught in this complex rhythm, not masters of it. That is the point of this collection. For it is right here, in the contemporary tango of history and memoir, that crucial questions of narrative authority in our times are being resolved. Or perhaps not resolved, any more than the mysteries of the past can be solved. We have gathered testimony from the eldof play, of battle, of the writing of history and the writing of a lifefrom practitioners who have to contend with these devilish problems at the level of the paragraph and the sentence. Consider these essays, then, as dispatches from the front lines. The front lines of narrative documentary writing in our times.

The evermore pervasive use of the rst-person voice in forms of nonctionjournalism, history, even biographythat were once pristinely shrouded in distant (omniscient) third-person narration held aloft by citations and sources, is no small cultural shift. Who tells the story can be as crucial as the story told. What does it mean to the writing of history that the rst-person voice has claimed new authority, that memoir is sometimes seen not as material for history, but as history itself? And what does it mean to literature that memoir has become the signature literary genre of the age? Where is fact? Where ction? Where is the truth in the disputed ground of nonction storytelling? Where does documentary authority residein the footnote or the footprint?

History has always relied on personal documents. Nothing new there. Letters, diaries, even family account books and ledgers have long been the gold standard of authenticity in history writing. These are the most primary of primary sources. But when autobiographical writing claims historical rights of its ownnot as a source but as an act of historythen the equation has changed. So too in literature, when the personal story claims the authority of nonction while clinging to the gripping suspense and charms of ction. Where are readers to place their trust?

Every writer consciously (or even unconsciously) reaching from the margins to the center for political and social power instinctively presents the personal storythe memoir, in effectas a radical document, to be read as personal and public. Surely the most important autobiographical work of mid-twentieth-century America is The Autobiography of Malcolm X. A personal story, but one properly read as history, taught as history. The womens movement in its various strands also gave rise to an astonishing array of memoirs in the late twentieth century and beyond. And the Holocaust and the Gulag have provided a vast bibliography of memoirs, so much so that they have created new elds of social and historical study rooted in autobiographical documents and personal testimony.

The personal is political, the womens movement of the 1970s asserted with almost gleeful fervor. But with the rise of the memoir in the nal quarter of the twentieth century, not only politics in the present, but the aloof enterprise of history began to take on a strikingly personal voice. Meanwhile the novel, for two hundred years the narrative sovereign of literature, began looking over its shoulder at the upstart memoir.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984.