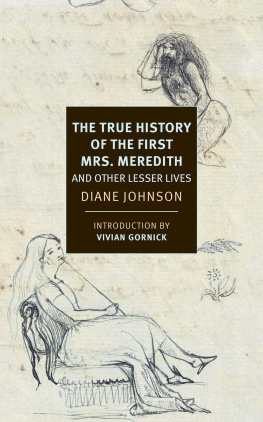

Also by Diane Johnson

Lulu in Marrakech

Into a Paris Quartier: Reine Margots Chapel and Other Haunts of St.-Germain

LAffaire

Le Mariage

Le Divorce

Natural Opium: Some Travel Takes

Health and Happiness

Persian Nights

Dashiell Hammett: A Life

Terrorists and Novelists: Essays

Lying Low

The Shadow Knows

Burning

Loving Hands at Home

Fair Game

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA | Canada | UK | Ireland | Australia | New Zealand | India | South Africa | China

penguin.com

A Penguin Random House Company

First published by Viking Penguin, a member of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright 2014 by Diane Johnson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Portions of this book appeared in different form as The Generals in National Post (Toronto), The Writing Life in The Washington Post, Stanley Kubrick: 19281999 in The New York Review of Books, and A Passion for CarsJust Dont Make Her Drive Them in The New York Times.

Photograph credits

Pages : Lucy Gray 2013

Page : Mnchner Stadtmuseum, Sammlung Fotografie, Archiv Landshoff

Other photographs courtesy of the author

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Johnson, Diane, 1934

Flyover lives : a memoir / Diane Johnson.

pages cm

ISBN 978-0-698-13748-6

1. Johnson, Diane, 1934 Family. 2. Moline (Ill.)Biography. 3. PioneersMiddle WestBiography. 4. HomeMiddle West. 5. Middle WestBiography. 6. Middle WestSocial life and customs. 7. Novelists, AmericanBiography. I. Title.

PS3560.O3746Z46 2014

813.54dc23

[B] 2013036808

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity.

In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers;

however, the story, the experiences, and the words

are the authors alone.

Version_1

To my husband, John,

to James, Douglas, Kevin, Darcy, Liz, Amanda, and Simon,

and in loving memory of all the ghosts in this book

Portrait of Catharine A. Martin

Chenoa, Illinois, 1876

Knowing how little time (during youth and middle life when people are busy with the cares of life and raising a family) they have to think of their forefathers or to tell their children, I, in my old age will write what I know of my dear husbands family and of my own. And hope no one will destroy or throw away this Book, for I hope some of my grandchildren or grandchildrens children will think enough of their parentage to read what their old grandmother writes when she is... 76 years old, and probably will be laid in the dust long before this is looked at.

Catharine A. Martin

CONTENTS

FOREWORD

I had always wondered how the first settlers in Illinois, in the eighteenth century and the beginning of the nineteenth, survived the ruthless climate and isolation, how they managed to clear the tough woodlands to make their farms, how they taught their kids something about Shakespeare and Mozart, and eventually pitched in for a war like the Civil War though theyd barely seen a black person or encountered a slave. No one writes much about the center part of our country, sometimes called the Flyover, or about the modest pioneers who cleared and peopled this region. Yet their midwestern stories tell us a lot about American history. Migration patterns, wars, the larger movements, are after all made up of individual human beings experiencing and sometimes recording their lives.

Now that circumstance has taken me to live abroad much of the time, or overseas, as Ive learned to say for its hardship military ring, I have wondered more than ever about how the first travelers managed to keep with them some of the qualities of sweetness, stolidity, and common sense theyve become reputed forqualities that are hard to see now in certain politicians who speak for this region.

I became especially interested in some testimonies by long-departed great-grandmothers, simple stories but all the rarer because the lives of prairie women have usually been lost. Perhaps prairie women at the end of the eighteenth century didnt have the leisure to pick up their pens, or maybe they didnt think their lives were of interest. I came to think of the people whose stories I finally uncovered as kin to the Indian ghosts that so fascinated me as a child: wispy but material, brought forth from the dust of old attic trunks, in the voices of unsung and unknown people speaking out now and then about their lives two hundred years ago, people whose thoughts and ways somehow account for much about this country, at least in the flat region of cornfields and bonfires along what used to be called the Illinois Bottomsometimes French Bottomor, back in the seventeenth century when people began to move that way, Louisiane. A millennium before that, in lower Illinois, there was a city of native peoples called Cahokia that was bigger than the London of the time, and now is only a series of excavated mounds.

Maybe, as at the beginning of a Russian novel, I should list the names of some of the people who have spoken out from their jottings and letters on their way to Illinois. The earliest was a Frenchman, Ren Coss, who left France in 1711; then his grandson, a judge in Vermont, Ambrose Cossitt, who was born in 1749 and lived through the Revolutionary War. Ambroses daughter Anne, born in 1779, left an account of giving birth in an icy cabin up on the border with Canadaand of her religious obsessions during the Second Great Awakening of fervid piety that swept America at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Her husband, John Perkins, tells about seeing angels and devilsthose iconic New England figures that did not seem to follow people to Illinois (though my mothers hometown of Watseka was noted for having a well-documented case of possession, when Lurancy Vennum was inhabited by the ghost of Mary Roff).

Im afraid I found a couple of unreliable characters: Dr. Eleazer Martin and Dr. Charles Stewart Elder both strike me in their letters as a little dodgy in matters of the heart. But we cant choose our relatives, or which of them we take after; we can only try to capture a few traces of them. As Tolstoy tells us, individual stories are what add up to history. Catharine Martin left a longer memoir of her life with her abolitionist husband, Eleazer, in the newly settled territories of Ohio and Illinois, where they went as newlyweds in 1826. Their son-in-law Charles Elder writes from his encampment during the Civil War. Dolph Lain (my brothers and my father) wrote down his memories of life on an Iowa farm at the end of the nineteenth century, and about going off to the First World War in the early twentieth.