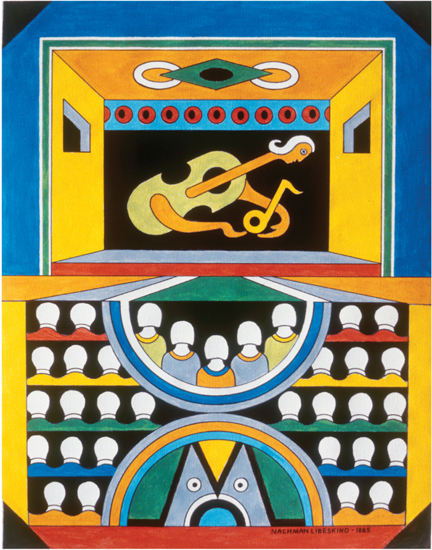

Nachman Libeskind, Sonata

Photo by Jeremy Berkovits

In the

Unlikeliest

of Places

How Nachman Libeskind Survived the Nazis, Gulags, and Soviet Communism

Annette Libeskind Berkovits

Foreword by Daniel Libeskind

Wilfrid Laurier University Press acknowledges the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund for our publishing activities.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Berkovits, Annette Libeskind, [date], author

In the unlikeliest of places : how Nachman Libeskind survived the Nazis, gulags, and Soviet communism / Annette Libeskind Berkovits ; foreword by Daniel Libeskind.

(Life writing series)

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77112-066-1 (bound).ISBN 978-1-77112-068-5 (epub).

ISBN 978-1-77112-067-8 (pdf)

1. Libeskind, Nachman. 2. Holocaust, Jewish (19391945)Biography. 3. PrisonersSoviet UnionBiography. 4. Holocaust survivorsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. 5. JewsPolandBiography. 6. JewsNew York (State)New YorkBiography. I. Title. II. Series: Life writing series

DS134.72.L52L52 2014 940.5318092 C2014-902732-X

C2014-902733-8

Front-cover image: Nachman Libeskind in Poland, 1934. Cover design by Blakeley Words+Pictures. Text design by Angela Booth Malleau.

Annette R. Berkovits, 2014

This book is printed on FSC recycled paper and is certified Ecologo. It is made from 100% post-consumer fibre, processed chlorine free, and manufactured using biogas energy.

Printed in Canada

Every reasonable effort has been made to acquire permission for copyright material used in this text, and to acknowledge all such indebtedness accurately. Any errors and omissions called to the publishers attention will be corrected in future printings.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written consent of the publisher or a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit http://www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

You can cage the singer but not the song.

Harry Belafonte

Contents

by Daniel Libeskind

Foreword

W hen my father died, I thought about a question someone once asked Goethewhat colour he liked best. I like rainbows, he said. And thats when I thought of my father; for him, the world was full of rainbows. He painted in an explosion of colours, shapes and patterns with a disciplined and finely tuned eye. My father died in June 2001, and I was grateful three months later that his death preceded the World Trade Center bombings of September 11. I was glad he was never witness to that seminal destruction and that he never lived to see his beloved New York attacked. Perhaps of us all, he would have been the most horrified and devastated, not only because of the loss of life but because America represented to him all that was good, safe, and upliftingand this was a vicious attack on all of that.

When my father died, a kind and decent soul left this world.

My first vision of New York was so iconic, that it is burned forever in my memory. In the summer of 1959, we sailed into New York Harbor on the SS Constitution. It was very early morning; my mother shook us awake and led us up to the deck to see the Statue of Liberty and the magnificent New York skyline. It was a most incredible sight; Lady Liberty pointing her torch to the sky. My father, who had arrived months earlier, had already fallen in love with the city. I remember his face, filled with love and beaming with excitement. Those imagesthe Statue of Liberty, the New York skyline, my fathers gentle face filled with optimisminformed my view of how Ground Zero should be shaped. I won the competition for Ground Zero in February 2003. The last months of 2002 and the first months of 2003 were frenetic and intense, filled with unimaginable tension and emotion. So what held me steady? Well, you are, in many ways, who your parents are: their values, their ethics, their humanity. I often think that what set my winning proposal for Ground Zero apart was, in large measure, the symbolism and the pragmatism of my parents lives.

Nachman worked on Stone Street, a few blocks from the original World Trade Center towers. While I was working on my proposal, I imagined my father walking past the site, almost on a daily basis and my mother in the fur-factory sweatshops. What would they expect from this tragic site? What would they experience as ordinary working people walking by those fateful blocks? Not for them the gleaming office towers, marble lobbies, sleek elevators. No, for Nachman and Dora, the site had to be public, had to be open, had to hold the memory of what happened there. It had to tell the story: the slurry wall, the bedrock, the memory of the Statue of Liberty. It had to have symbolism; the tallest tower soaring to 1,776 feet to commemorate the Declaration of Independence, the memorial plaza with the footprints of the fallen towers; waterfalls to bring nature and quietude. And a public plazathe Wedge of Lightformed by the line of light striking every September 11, precisely at 8:46 a.m., when the first jet smashed into the first tower; and at 10:28 a.m., when the second tower collapsed into dust and debris. With the towers rising in a spiral echoing the torch in Lady Libertys hand, all the elements would be like chapters of that dreadful daythe story that all New Yorkers would feel and see.

We moved to Berlin in 1989, to realize the Jewish Museum. Most members of our extended family were horrified. To willingly live in the city where the Holocaust was devised was a total anathema to them. But my father, ever the geographer, was not one to forget history. After the Berlin Wall fell, he walked with me through Potsdamer Platz; in its glory days, the commercial centre of Berlin. Now it was a site divided by the walla no mans land. We walked along until my father suddenly stopped. He stomped on the earth. Look at me, he said. Here I am. Hitler is nothing but ashes. But I am here and I am living, eating, sleeping in this city and below the Nazis bones are rotting! His eyes filled with tears but he sounded victorious.

Ten years later, in 1999, the Jewish Museum Berlin opened, empty. Chancellor Gerhard Schreder attended. After the formal dinner, the chancellor went to the table where my ninety-year-old father sat so he would not have to get up, knelt before him, and took his hand. Mr. Libeskind, you must be so proud. Thank you for being here. What a moment for my father and for me.

I applaud my sisters resolve to write this book. Striking a balance between oral history and recovered memory is complex and demanding. Nachmans storyin Lodz, Poland; in Russia; in Israel; and in New York is told not from an objective or independent point of view but rather from the insight, intelligence and love of a daughter.

Daniel Libeskind

Authors Note

T his memoir has been inspired by the remarkable survival and optimism of my father Nachman Libeskind whose tapes narrated in his native Yiddish and partially in English have served as a principal resource for this book. This story is also a product of a decades-long dialogue between father and daughter, reams of preserved correspondence, and my own research.