This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

iupress.org

2021 by Indiana University Press

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.481992.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Cataloging information is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-253-05683-2 (hdbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-05684-9 (pbk.)

ISBN 978-0-253-05686-3 (web PDF)

First printing 2021

CONTENTS

Introduction / Dawn E. Bakken

1.Pride, Patriotism, and the Press: The Evolving True Story of the First American Shot of World War I / Greta A. Fisher and Lauren E. Kuntzman

2.On Convoy Duty in World War I: The Diary of Hoosier Guy Connor / Edited by Jeffrey L. Patrick

3.A Hoosier Nurse in France: The World War I Diary of Maude Frances Essig / Alma S. Woolley

4.Oatmeal and Coffee: Memoirs of a Hoosier Soldier in World War I / Kenneth Gearhart Baker, edited and introduced by Robert H. Ferrell, transcription and postscript by Betty Baker Rinker

5.Recollections of a World War II Combat Medic / Bernard L. Rice

6.A Hoosier Soldier in the British Isles / Lawrence B. McFaddin

7.A Fair Chance To Do My Part of Work: Black Women, War Work, and Rights Claims at the Kingsbury Ordnance Plant / Katherine Turk

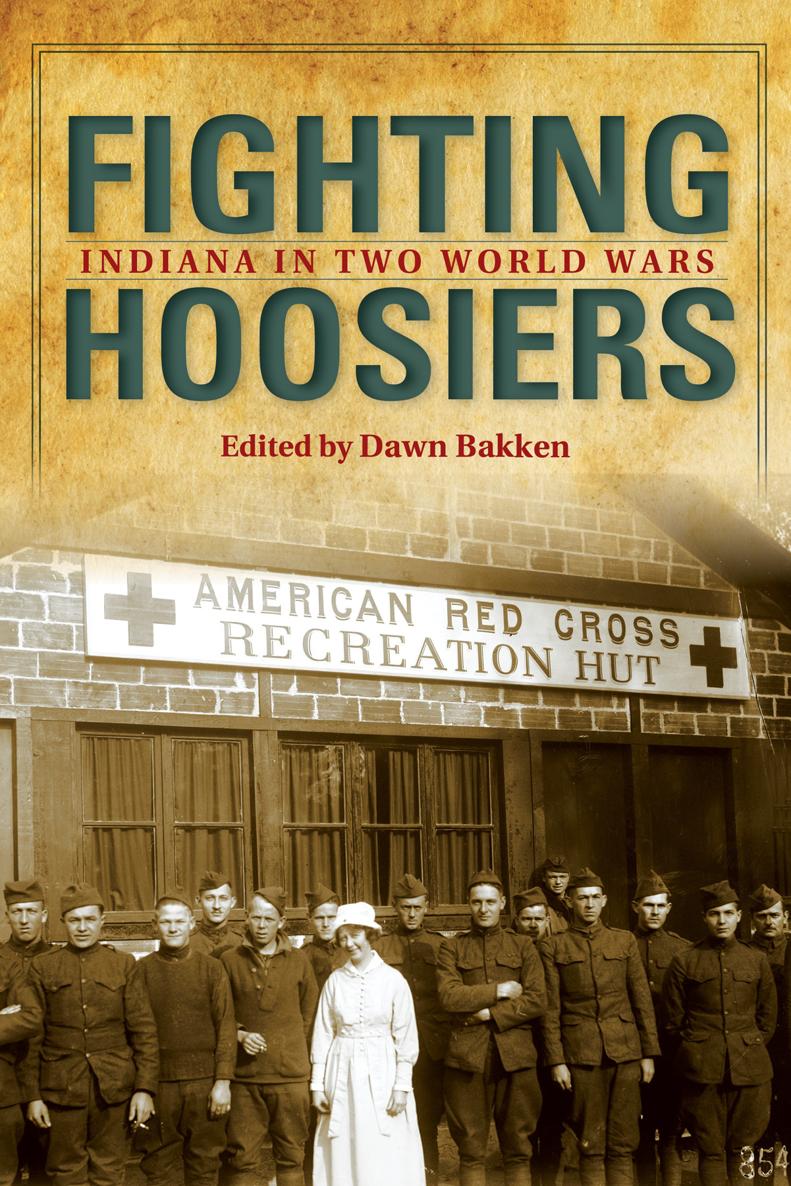

THE FIRST ISSUE OF THE Indiana Magazine of History (IMH) appeared in print in 1905. The IMH, a peer-reviewed journal sponsored by the Indiana University (IU) Department of History, is one of the oldest continuously published state history journals and now operates as part of IUs ScholarWorks. The journal publishes articles by academic scholars and independent researchers; its archive is also filled with original diaries, memoirs, and letters. Many of those primary source documents were written by Hoosiers on the battlefrontfrom territorial days to the twentieth centuryand by their loved ones back home.

This collection showcases seven articles on Hoosiers in the two world wars of the twentieth century. Four reproduce original diaries, letters, and memoirs. Readers will meet, among others, Alex Arch, a Hungarian-born immigrant who was the first American to fire a shot in World War I; Guy Connor, a radio operator on convoy duty in the Atlantic; Maude Essig, a nurse serving with the Red Cross in wartime France; Kenneth Baker, who crawled across French battlefields (sometimes over and around dead bodies) to lay phone lines for military communications; and Bernard Rice, a combat medic who witnessed the liberation of Dachau.

Twelve years after the IMH began publication, on April 6, 1917, the United States entered the Great War. Among the first who registered for military service were 260,000 Hoosiers. By the end of the war, 400,000 more had registered; more than 3,000 Indiana men and women had died.

One Hoosier soldier played a prominent role at the outset of American involvement in the war. On the night of October 22, 1917, members of Battery C of the US Armys Sixth Field Artillery, with the loan of shells from a French unit and some assistance from a French officer, dragged an artillery piece through the mud into an abandoned gun pit and, at 6:05 a.m. the next morning, fired toward German troops. On October 24, US newspapers reported that a young soldier had fired the first American shot of the war. The early stories described a redheaded sergeant from South Bend, Indiana, as the man who had pulled the lanyard. The unnamed soldier had told a reporter that he hailed from South Bend and proud of it!

The ensuing media frenzy to determine the identity of the soldier is described by authors Greta Fisher and Lauren Kuntzman. In their extensive survey of period newspapers, they found that readers, newspaper editors, and local boosters were quick to fill in the story with their own details. One South Bend newspaper promoted a local man who had worked at the citys Oliver Chilled Plow Works before the war. The War Department, however, identified the soldier as a corporal who had been wounded and, not coincidentally, was headed back to the States for a government-sponsored tour promoting Liberty Bonds. In September 1918, nearly one year after the incident, the commanding officer of Battery C publicly confirmed the identity of the Hoosier soldier who had fired the first shot. Intense media coverage, public spectacle, and misinformation (at least some of it deliberate) are not the sole purview of modern times.

Many other Hoosier soldiers served no less bravely but without media scrutiny. Guy Burrell Connor enlisted in the US Navy in June 1917. After a short duty aboard the battleship USS Pennsylvania, Conner was transferred to the USS New Hampshire, assigned to transatlantic convoy duty. Connor was an electrician first class, who manned the ships radio and fixed electrical equipment when needed (including going aloft to fix a broken antenna).

Connors first experience of convoy duty took place in September 1917, when eleven transport ships, one cruiser, two destroyers, and the USS New Hampshire convoyed more than twenty thousand American troops across the Atlantic. His diary captures the challenges of naval warfare in the early twentieth century. Communication by radio meant that as his ship sailed farther into the Atlantic, the radio signals from the United States grew weaker. As the New Hampshire approached Europe, Connor could contact the naval base in the Azores, which served as an important refueling stop and shore leave destination for American ships and soldiers.

The New Hampshire was powered by coal, and Connor relates the tedious, multiday process of coaling the ship, both in the Azores and in New York. Through mechanical problems, an Atlantic hurricane, and the outbreak of the Spanish flu, the New Hampshire continued its duty until the Armistice, which Connor notes in his diary entry for November 11, 1918.