TALES

________ OF ________

BIALYSTOK

A Jewish Journey from Czarist Russia to America

First Printing: November 15, 2017

Tales of Bialystok: A Jewish Journey from Czarist Russia to America

Copyright 2017 by Phyllis Goldberg Ross

All Rights Reserved.

ISBN-10: 1578690048

ISBN-13: 9781578690046

ISBN : 9781578690053 (e-book)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017942822

Published by Rootstock Publishing

www.rootstockpublishing.com

An imprint of Multicultural Media Inc.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the author. The only exception is by a reviewer, who may quote short excerpts in a review.

Front Cover Design by Stephen McArthur

Book Design by Carrie Cook

Printed in the USA

DEDICATION

To my father, Charles (Zachariah) Goldberg, of blessed memory, and to his descendants with the hope that his words will be meaningful to them and help them to appreciate a very special man.

The Goldberg Family from Menkhes Street, left to right, Reb Isaac, the cantor; his children Beilke, Daniel, who was mayor of Colchester CT, Charles Zacariah, their mother Keyle, and daughter Sheinke.

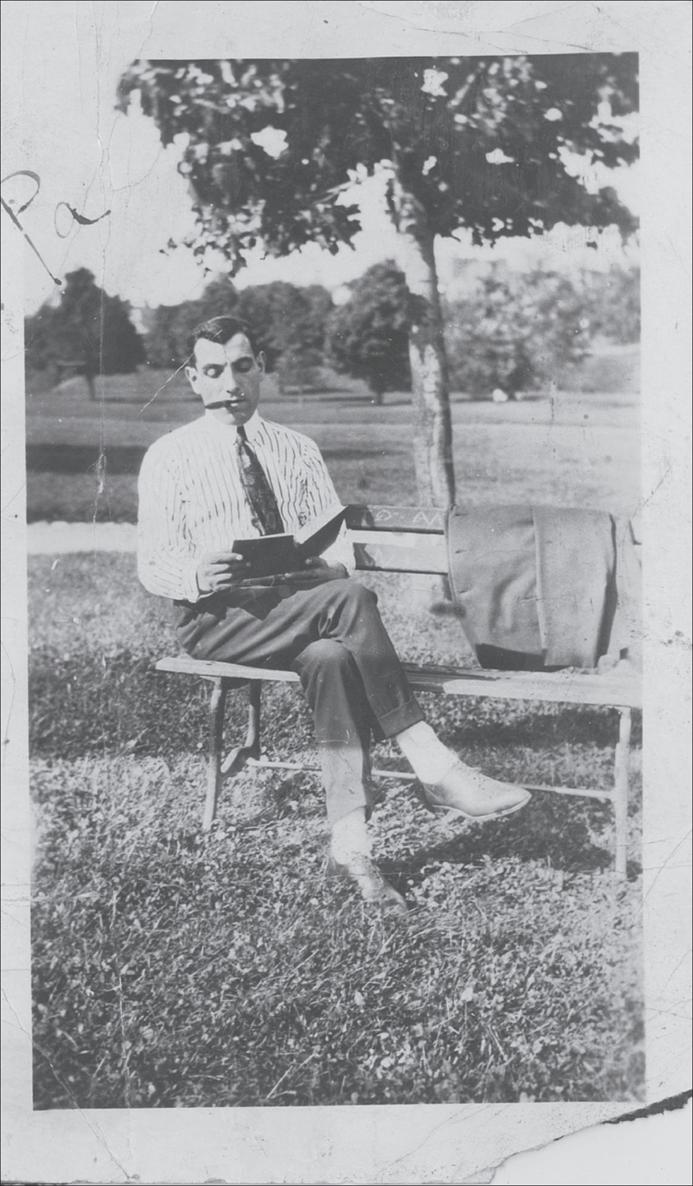

Charlie as a young man in America.

THE MAGIC OF THE WRITTEN WORD

A Foreword from the Translator

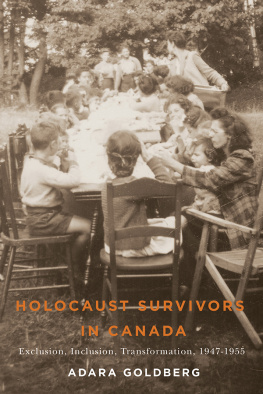

M y father, who died in 1954, never had much formal education. He was born in Bialystok, Poland and came to the United States in 1906 at the age of 17 after a devastating pogrom in his hometown. From time to time after his arrival in America he wrote letters to the editors of some of the New York Yiddish-language newspapers; those that were published, he cut out and pasted in a notebook. In the 1940s, my father started to write what he called episodes from his youth. Many of these stories were published in Yiddish newspapers and in the Voice of Bialystok, the journal of his landsmens society. I knew he kept a notebook of these clippings, but he never spoke about them. Since they were all in Yiddish I had no idea what was in them. He died in 1954 and my mother kept the notebook until she died in 1982. In looking through my mothers things, I found the notebook; in all the years since her death I never even opened it.

At the turn of the millennium, I suddenly decided it was time; these stories could be a legacy for future generations. The only problem was that, although I could speak Yiddish, I couldnt read it. Yiddish is written using Hebrew letters. I knew the Hebrew alphabet, and little by little I taught myself to read Yiddish and began translating the episodes into English. The results were incredible. I learned things about my fathers life that he had never spoken of: How he had been apprenticed to a furniture maker for three years beginning at the age of eleven with only bed and board as his wages; at the end of three years, his parents were paid 20 rubles. What it was like studying with a cruel teacher in a Talmud Torah in Russia before the turn of the 20th century. How he had barely escaped a group of marauding Cossacks. How he had fled Czarist Russia by traveling at night from safe house to safe house via a kind of underground railroad, and many other fascinating, often sad, experiences. He also related stories about events that he had not experienced but were told to him and obviously made a significant impression on him. Because my father committed his thoughts to paper, I have found out things in my fathers life that would have been lost forever, and can share them with others.

Phyllis Goldberg Ross

August 2017

Special thanks to Kenneth Newman, Ellen Ross-Newman, Rhoda Carroll, and Tim Joslyn without whose assistance this project could not have been completed.

A note from the translator: The Yiddish word for czar was pronounced as tsar, which means trouble, woe. The Russian ruler was certainly the source of a great deal of pain and suffering for the Jews of Russia at that time. Its a word play which doesnt come through in the translation.

From a Painting of oldest Jewish street in Bialystok.

Count Jan Klemens Branicki II (1689-1771) The owner of Bialystok, gift of the Czar.

The old Jewish cemetery 1917, now disappeared.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

by I. Shmulewitz

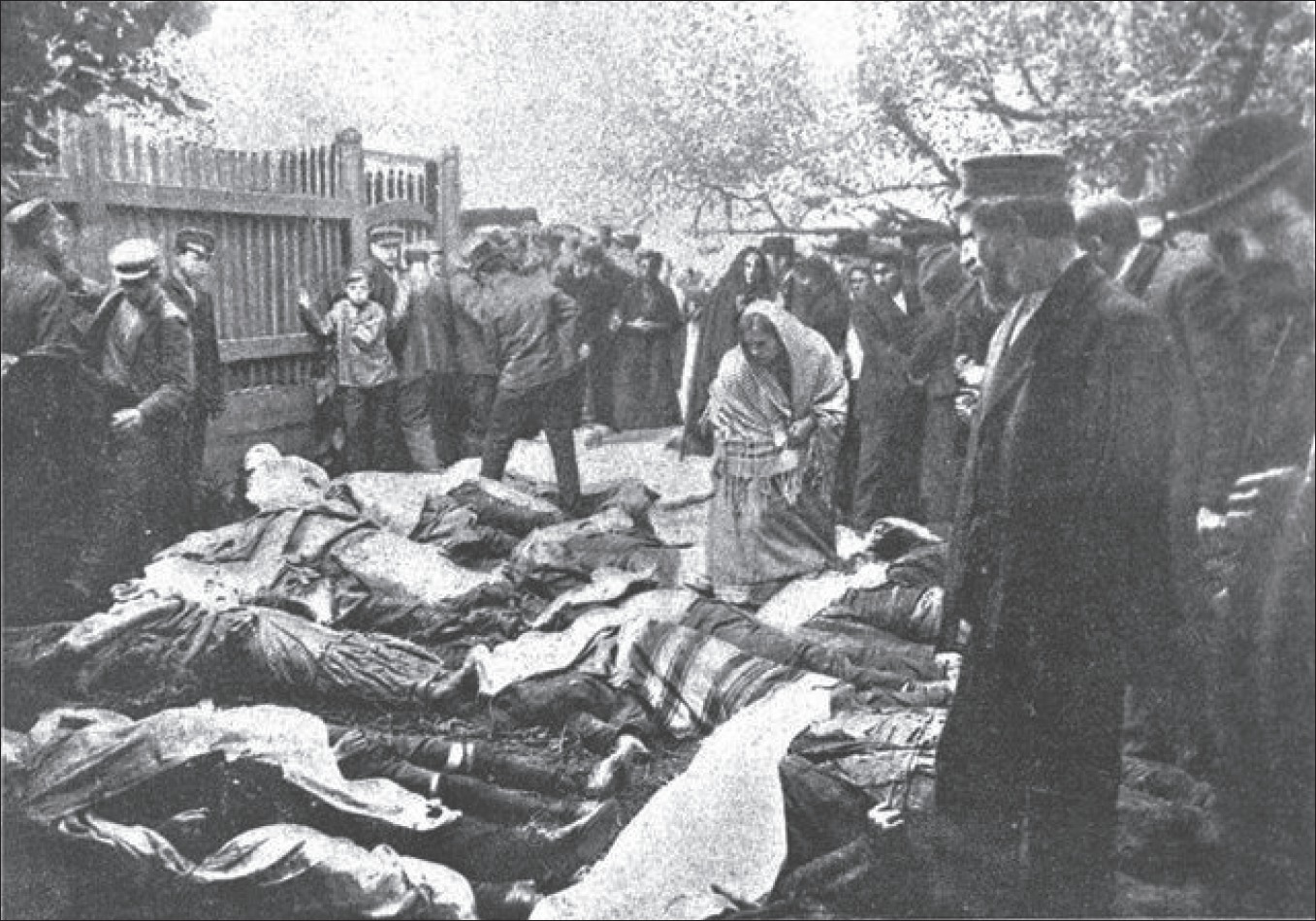

In front of the Jewish hospital, in the aftermath of the June 1906 Bialystok pogrom.

IN THE SHADOW OF DEATH

T his happened in the year 1906, in the time when waves of pogroms spread over cities and towns all over Russia, and Jewish blood poured out like water, including in the city of Bialystok. Several weeks beforehand we already knew that the local regime had decided that our city would have a pogrom. We heard the information from the Jewish soldiers who were serving in the city militia.

The young Jewish men decided to set up a self-defense organization, and as a young man myself then, I also joined the group. Feverish activity began. We drilled and were assigned various responsibilities; we prepared ourselves exactly as if for a war. Naturally, everything was done in strict secrecy.

The day came that had been designated in advance for the pogrom. From quite early on a lot of restlessness could be detected among the peasants. There was a lot of commotion in the marketplace; the air seemed filled with gunpowder. The shops were closed. Very few Jews showed themselves in the street. And if a Jew was seen, he was running and not walking. One could read the fright on every Jewish face.

Eleven oclock. The self-defense group sends out patrols. At exactly twelve oclock a religious procession is supposed to pass by. That is to be the signal to begin the slaughter. And now the lonely tolling of the town clock is heard. Each clang is a monotone: one, two, threeand so on until twelve.