Perditus Liber Presents

the rare

OCLC: 760033924

book

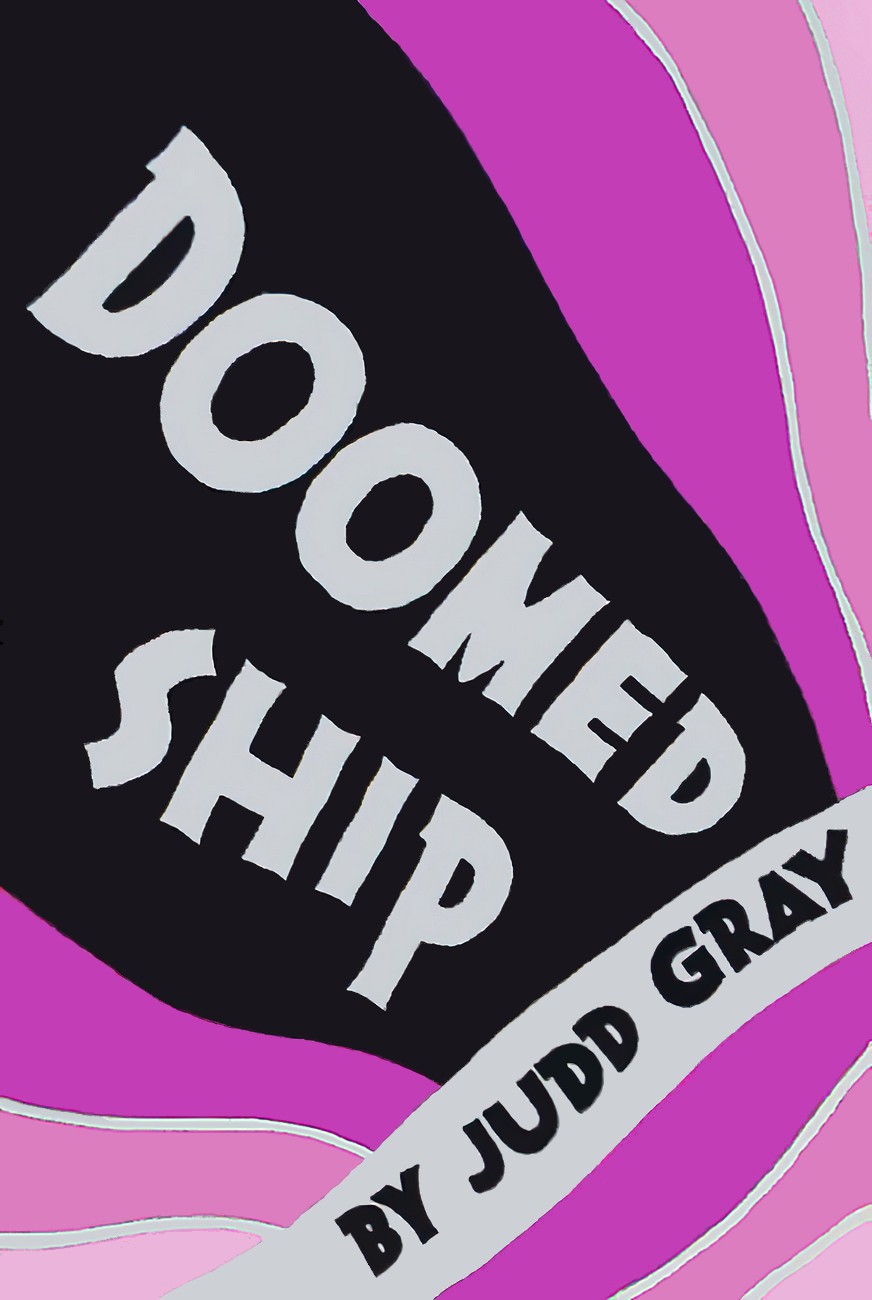

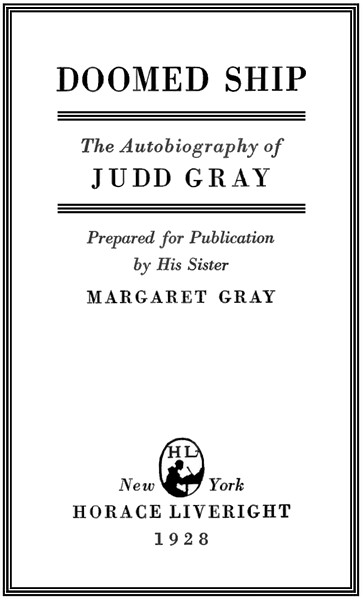

Doomed Ship

By

Henry Judd Gray

Published 1928

DOOMED SHIP

TO MY FAITHFUL LITTLE MOTHER

Did you ever stop to think back to baby days to try and recall the very first impression or memory in life? No? Well, perhaps that is because it didnt interest you sufficiently to do so or else that you didnt have the time. It is queer, but my first concrete memory is awaking with my head in my mothers lap stretched out full length in a church pew. I guess I was about four; so being normal sleep meant more to me than hymns or the Gospel of God. My second impression that registered in ink on my childish brain was trying to speak a piece in Sunday School (after careful training by my mother) only to get stage fright, and my sister who. was to speak her part first, fortunately knew mine thus the day was saved as far as the piece was concerned. It seems strange to retrospect to that age and find Christ Jesus connected in both cases with these indelible memories of four years of wisdom? Especially in the face of my recent acceptance of Christ as my Saviour, and that By grace are ye saved through faith; and that not of yourselves: it is the gift of God: not of works, lest any man should boast. Eph. 2:8,9.

PUBLISHERS NOTE

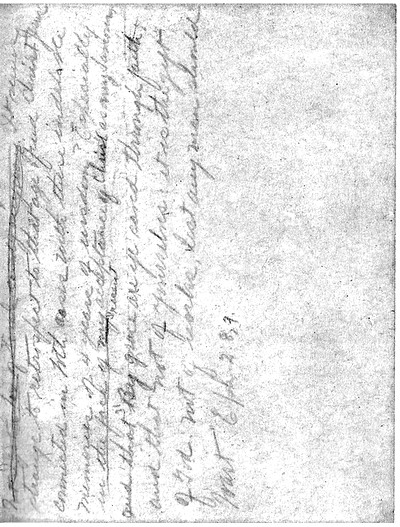

THIS work in manuscript was written with a pencil on both sides of the sheets of an ordinary scratch pad. The lines are close together. The complete work covers 229 pages. The work was finished by Judd Gray on January 11, 1928, less than an hour before his execution. He had left instructions that the manuscript was to be given to his sister, Mrs. Margaret Gray Logan. This was done after his death.

In preparing this extraordinary document for publication Mrs. Logan has been careful not to add or delete any matter of the slightest meaning or importance. Unfortunately there was matter without meaning in the original, occasional hysterical religious expressions, repetitions, very obscure sentences, which if left in, would have made the work practically unreadable. The title and chapter quotations were added by Mrs. Logan. The original manuscript is in New York in the possession of Mr. Samuel Miller, Mrs. Logans attorney.

The work is a unique document, and very likely the only one of its kind known in the annals of English or American criminal history. The publishers guarantee the authenticity of this work.

H ORACE L IVERIGHT , I NC .

Contents

............. 9

............. 69

............ 215

...

PART I

The very good and the very bad are both rare,

and the greater part of men are between the two.

PLATO

PART I

SHADOWS Retrospection brings my first concrete memory. A shimmer of sunlight picks out the gold-lettered passages of Scripture on the terra-cotta tinted walls. Warm and perspiring I catch a wink of sleep. A persistently whirring fly lights on nose and I move my head about in my mothers lap. She strokes my hair with her gloved hand. The sermon was long and the day was hot, even though the big white stone church repulsed the suns rays. My eyes knew every crack and seam and blemish in the pinkish ceiling and side walls within their range. The voice of the minister surged and receded as he spoke of Heaven and Hell. Sometimes he banged with his fist on the lectern. If I raised my head mother would fan me with a cardboard fan that had a beautiful girl pictured on it. She had very red cheeks, blue eyes and yellow curls, and I fancied she was eating a heaped up plate of ice cream. My white sailor

suit was starched stiffly, it pricked through my underclothes; I felt uncomfortable. I whispered loudly to my mother, May I have a plate of ice cream if he ever gets through? Snickers around me.

The minister announced the hymn, the organ came to life and bellowed forth. Church was over. The very special piece Sister and I learned so thoroughly to speak on the very special occasion in Sunday School. The crowded room, standees at the rear. A new multi-ruffled frock of blue organdie on Sister, a bouquet of flowers, yellow and blue, crushed in her hands. For me, a long trousered, inevitably white sailor suit, a thick black silk cord dropping a silvery whistle about my neck. Sister and I were on the platform; my turn to speak. Not a syllable could I utter. I was tongue-tied. After an interval a low-voiced teacher behind a screen prompted me. Still no sound emerged from my stiff and paralyzed lips. Finally, Sister, after despairing glances at me, repeated the duo, solo. We both bowed our departure. I could, it seemed, still bend my knees.

Sister felt the humiliation deeply and cried herself to sleep. But I went to sleep quite happy with my new silvery whistle tucked under my pillow.

I would be feeling almost well on school days, then on Saturdays when parties happened I would ill. And I would watch Sister go to a party. She would promise faithfully to bring me my favor and perhaps some candy. My eyes would wink tears until mother laid aside her sewing and gathered me in her arms. She would hold me close, promising, Annie will bring us cocoa and toast and we will have a party, just you and I. Then she would rock me (I was a very small child for my age). It is not fair, I would whine, Sister can always go and I am always ill. Never mind this once, my mother would console me. Sometime you will be big and strong and go too.

Once, dressed in a blue serge suit, white Eton collar, huge black bow tied under my easily obliterated chin, my sister in her party dress of transparent white material, a floppy blue satin ribbon sash and a crop of made curls instead of her

straight brown hair, proudly dragged me to a long-promised party. In almost no time at all I was ignominiously yanked home decidedly ill; my tie ruined and my sister claiming supreme disgrace from my unhappy condition.

Luckily I managed to keep up to grade in school, regardless of the fact that I was out nearly half the terms due to all manner of contagious diseases barring smallpox and scarlet fever. Perhaps in one of these illnesses was born my dream of becoming a doctor. Sister and I attended a small private school. On the days following severe rains we always quarreled about the dead angleworms as thick as hops on the sidewalks. She insisted on stepping over and around them. I insisted that they were harmless and that it was proper to walk naturally. They made her nervous. She cried and contended to mother that she could not go to school with me when the streets were in that condition. She cried very long and hard. I thought such things were silly and told her so. In spite of her boundless fear of worms she was always yearning

to fight my battles. She would go out of her way to call to terms any one who had intimidated me, regardless of his size. She was vigorous and dependable and always seemed to know just what she wanted to do next. I was the opposite: never able to decide things quickly. Things either worked or they did not, and I took the consequences.