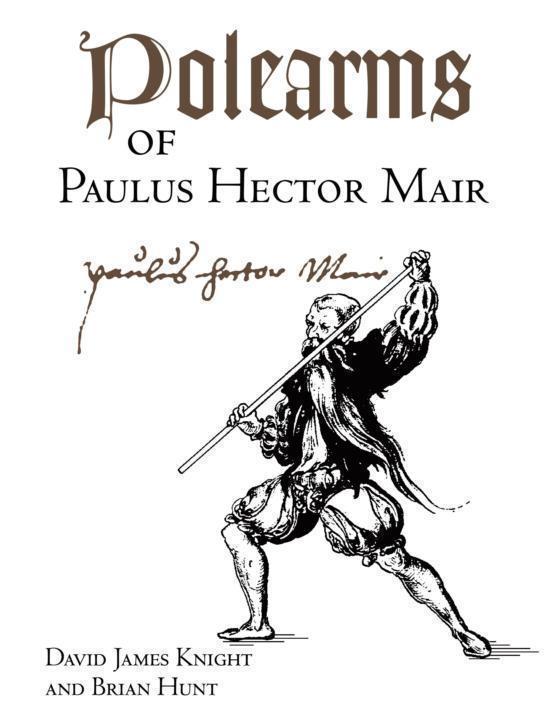

DAVID JAMES KNIGHT AND BRIAN HUNT

In hoc libro continentur artis athleticae non solum habitus selectissimi atque approbatissimi, verum etiam vitandi et inferendi ictus subtilior quedam ratio, et scientia, quibus si quis rite usus fuerit, facile in palaestra, equestri concursu, et torneamentis victoriam obtinebit.

Turn etiam complectitur figuras gladiatorum concertantium ex ornatissimas declarationibus habituum adiunctis: addita item sunt torneamenta ante annos quingentos in Germania exercita isti itaque habitus a doctoribus gladiatorum peritissimis excogitati et accersiti, per Paulum Hectorem Mair civem Augustanum non citra magnos labores et sumptus, in honorem principium, herourn, atque artis gladiatoriae amantium nunc demum in lucem edita sunt.

Cod. Icon. 393, 1r

In this book you will find the Art of Athletics, not only its most carefully selected and proven techniques, but also its more subtle strikes, which certain doctrines and teachings have shunned and criticized, yet which, when used properly, will allow you to easily obtain victory in fighting academies, knightly combat, and tournaments.

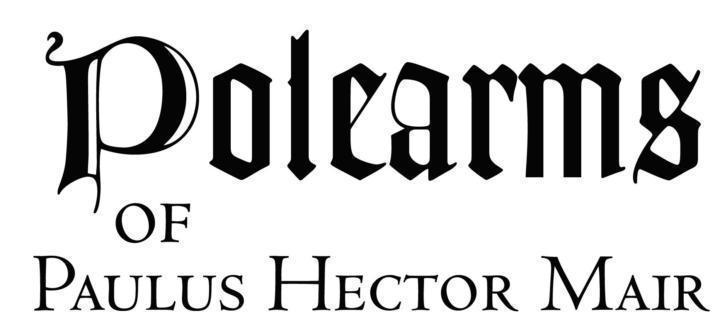

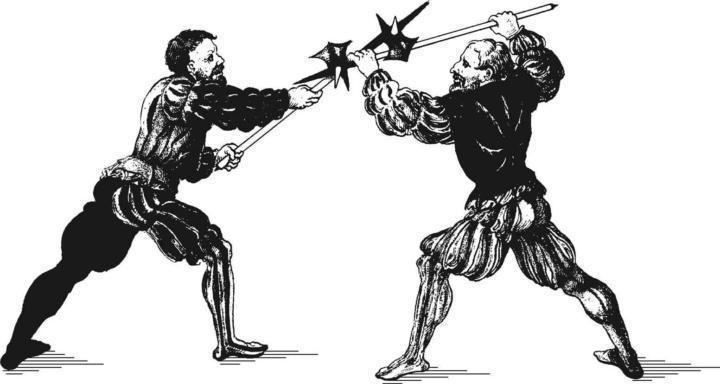

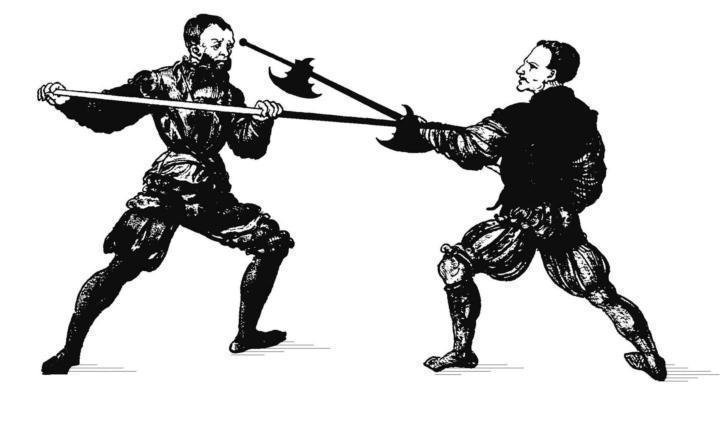

Also included are elaborate illustrations of athletes fighting according to the techniques therein

Thus these techniques, devised and compiled by the most knowledgeable Masters of Athletics, are now brought forth into the world, after considerable labor and expense, by Paulus Hector Mair, burgher of Augsburg, in honor of the Prince, the Hero, and the Lover of the Gladiatorial Arts.

David James Knight would like to thank Professor Kathryn McKinley pro disciplina egregia sua; Jackie Ege fur alle ihre Mithilfe; Mike Cartier and ARMA South Florida for their help in testing and interpreting each translation; the Hunts and Feils for their hospitality; Jon Ford for his tremendous patience; Dieter Bachmann for his assistance with the Hils manuscript; and the good taxpayers of 16th century Augsburg, without whom none of this would have been possible.

Brian Hunt would like to thank his family for their support of his mad hobbies; Eli Combs for his input on the German language; Stewart Feil and his friends in the ARMA Provo group for helping him work out interpretations and ideas; and all those who have published on our subject and contributed to the growing knowledge of others.

Both authors would like to extend their immense gratitude to Saxon State Library for its generosity and to John Clements, director of ARMA, for his instruction and guidance.

In the 1540s, the municipal official and student of fencing, Paulus Hector Mair of Augsburg, compiled what are likely the most immense and diverse works on martial arts ever produced. Mair's unique and invaluable opus compendia are among the greatest representative examples of both our Western martial heritage and 16th-century technical literature. The work is unequivocally a major resource for historical fencing studies today. Technically detailed, pragmatic, and carefully illustrated, it is presented, with a conscious effort, scientifically and scholastically as a textbook. More often than not the lifelike artwork is nothing short of gorgeous, capturing the energy, balance, and motion of its fighting figures.

In the writings, Mair, himself a collector of fencing books as well as a student of the art, referred to the subject by the Latin, artes athleticae. Mair (pronounced "May-er") tells us that he learned his own skills from renowned experts and was ambitiously determined to present and illustrate only those techniques that he personally knew or that had been performed for him by experienced practitioners of the craft. These fighting disciplines were pursued as a science of defense. It was a tradition conceived over time by necessity as a way of preventing or executing personal violence. As such, these systems were arts in that they were a branch of learning consisting of skills derived from the intuitive cultivation of experience and attained by rational practice, contemplative study, and empirical observation. Whether as military trade, commercial craft, or private learning, students of the subject applied its principles and methods in the exercise of open-ended and evolving activities. This is certainly the case with regard to the polearm material presented here.

Fencing as a martial art at this time consisted of such fundamental elements as the use of single and two-handed swords, daggers, shields, and polearms; coordination of two-weapon combinations; fighting in armor; grappling and wrestling; body throws, joint manipulation, and trapping holds; kicks and empty-hand strikes; disarming techniques; facing multiple opponents; fighting mounted and on foot, and the practice of mockcombat bouts. These long-forgotten aspects of allbut-extinct European traditions of personal self-defense have remained entirely outside the scope and expertise of Western fencing knowledge as it has existed in modern times. But as with so many other sources of Renaissance martial arts literature, these elements are all evident within the work of Paulus Hector Mair.

Concerned with both military and personal self defense needs, Mair uniquely presented a greater range of weaponry and individual self-defense teachings in his work than any other single source of historical European martial arts. Along with grappling and wrestling, Mair's collection of combatives included methods for using the dagger, longsword, short sword and buckler, early rapier and dagger, the cleaver-like dussack, longstaffs, halberd, saw-tooth sickle, great flail, heavy club, spear and bastard sword in armor, as well as addressing aspects of mounted combat. Throughout his immense treatise the systematic techniques depicted reflect an undeniable energy and coordination. Whether in grappling, thrusting, or striking, they portray athletic, quick, fluid movements and actions of guarding, striking and counterstriking-typically employing the long, lunging footwork and wide, agile stepping so signature of the martial arts of Renaissance Europe. Mair also offers what is probably the most thorough material on polearms in martial literature from the era. The images on the shortstaff alone in most editions of Mair's work could easily be the envy of many a modern book on similar Asian weapon teachings. It is this that makes up the content of this present volume, the first of its kind exclusively on the historical polearm techniques from the Renaissance martial arts.