Pagebreaks of the print version

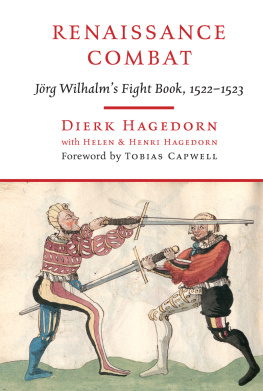

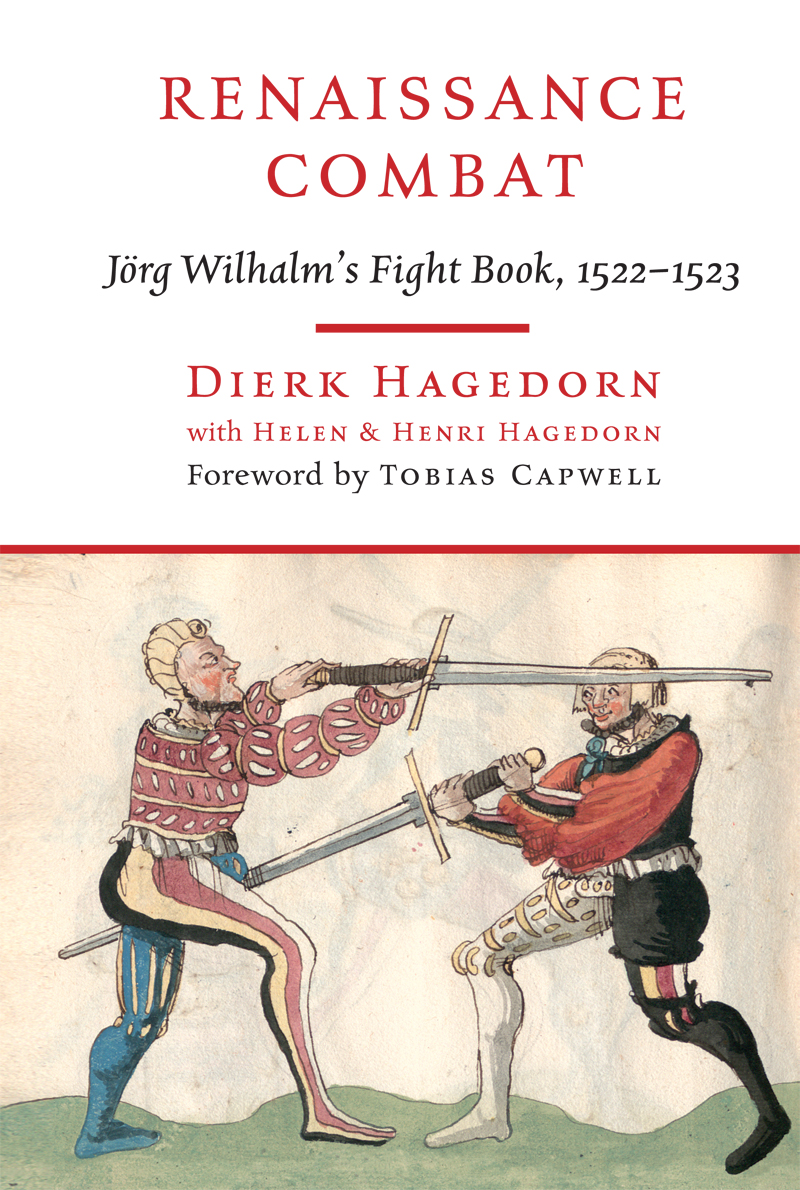

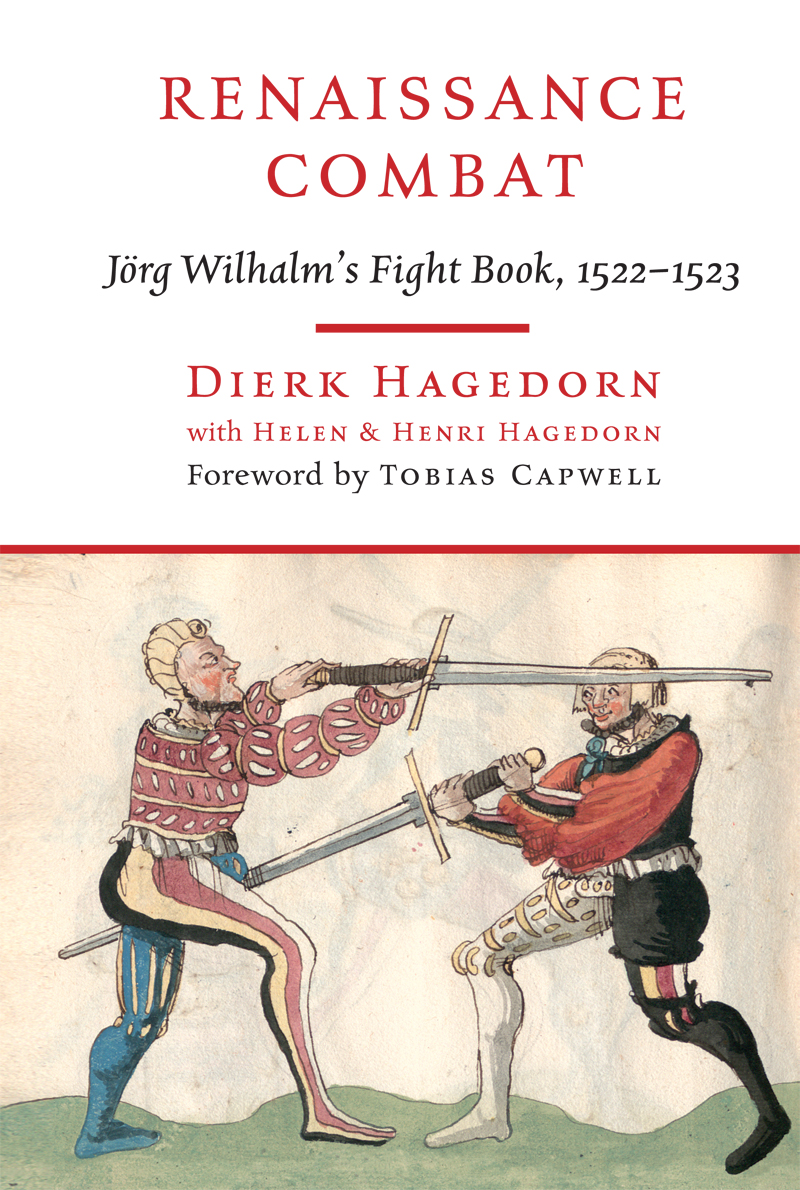

RENAISSANCE COMBAT

RENAISSANCE COMBAT

Jrg Wilhalms Fight Book, 15221523

D IERK H AGEDORN

with H ELEN & H ENRI H AGEDORN

Foreword by T OBIAS C APWELL

Published in 2021 by Greenhill Books,

c/o Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, S. Yorkshire, S70 2AS

www.greenhillbooks.com

Dierk Hagedorn 2021

The right of Dierk Hagedorn to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with Section 77 of the Copyrights Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

ISBN 978-1-78438-656-6

ePUB ISBN 978-1-78438-657-3

Mobi ISBN 978-1-78438-658-0

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data available

T OBIAS C APWELL

FOREWORD

For hundreds of years, an entire genre of medieval and Renaissance European literature and visual art has remained largely unnoticed. It is a fabulously rich and immediately revealing body of tracing its origins back to the late thirteenth century (at least) and extending through the late medieval period, through the Renaissance, and well into the modern era. It is comprised of thousands of unique manuscripts and early printed books. While these enigmatic volumes were never completely unknown, their early cataloguers in libraries, archives and museums tended not to know what to make of them.

The fight book is unlike most other books. It cannot simply be read and understood. Its use requires not only exceptional scholarly talents fluency in old languages and mastery of the art of palaeography but also considerable experience with traditional hand weapons and their use. Not only does the reader need to know the esoteric terminology of fighting, he/she has to have a personal, practical understanding of what being in a fight feels like how the speed of the action can suddenly change, how the opponent will try to control your state of mind, how the precise length and direction of a step or the angle of an attack can mean victory or defeat. The fight book tries to convey practical ideas to literate martial artists, thoughts which are intended to soak into the mind of the reader and thus assist his/her physical practice. Without that practice however, the fight book is largely useless. No one ever became a great sword fighter by reading books.

The fight book is not meant to exist or be used in isolation; it is intended to work as part of a very specific environment, a place where the ability to fight well with the sword, dagger, axe and spear was a vital life skill, where being trained and ready to confront ones enemies in full plate armour could earn one money, fame and prestige. Again, these skills could not be found in the pages of any book, but only through rigorous, dedicated, single-minded practice. Maintaining the necessary mental focus is as difficult, if not more difficult, than enduring the required physical exertion and punishment. This may be where the fight book finds its place in the world of combat.

When I look at a fight book, especially one such as that of Jrg Wilhalm produced during the German Renaissance, I feel many things. As an art historian I am immediately drawn in by the books value as a work of art, a visual document of aspects of the material culture of its time. As an arms and armour specialist, I am pulled deeper by the way it hints at the original, living context of objects which I normally study in the disassociated setting of the library, museum and laboratory. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, as someone who has practised martial arts since childhood, the fight book makes me want to be a better fighter. It inspires me with a renewed sense that however much I have learnt, however well I may be able to defend myself, there is always more more technique, more variation, more subtlety. The fight book is a spur to physical practice.

For these reasons, it should come as no surprise that historically, most curators, scholars and archivists have had no idea what to do with this material. We should not blame them. Working with this material is an enormous challenge, requiring a combination of key skills and knowledge that have not been employed together for hundreds of years. The person who wrote the fight book, and the original intended readership, regarded letters and combat to be equal parts in a respectable education. Ultimately, this remains the only way to truly understand the fight book.

Over the last few decades, I have watched with enduring fascination as the modern historical European martial arts community has grown, proliferated and thrived. When I looked upon an original fight book for the first time (the now world-famous I.33, ), sitting in the library of the Royal Armouries in the Tower of London almost thirty years ago, I could never have imagined that these books would soon inspire thousands of people across the world to dedicate significant portions of their lives to the study and practice of these ancient fighting systems. It is a remarkable culture, one that has expanded immeasurably our understanding of the real human experience of life in the past.

As already noted, the interpretation of these illustrated texts requires special academic and practical gifts. When I first met the author of the present volume, it was not in an archive. I was standing outside the walls of a fortified manor house in central Germany, clad in full plate armour and armed with a pollaxe. I faced another similarly equipped person, whom I had never met. Indeed, the only hints of his identity were the round-rimmed spectacles peeking out of the gap between sallet and having accepted the honour of being hit by him, I was pleased to attend one of his practical clinics, where he discussed the contents of a German longsword treatise with the ease of true authority, and with, literally, a sword in one hand and a book in the other.

Jrg Wilhalm and the reader are in good hands.

Tobias Capwell is Curator of Arms and Armour at the Wallace Collection in London .

INTRODUCTION

Still sharp. B OROMIR , The Lord of the Rings :

The Fellowship of the Ring , 2001

I came to realise that Jrg Wilhalm can still be dangerous today, although hes been dead for almost five centuries: when I pulled some printouts used in the preparation of this edition out of the printer, I cut myself on a sharp edge of the paper. I bled only a little. The combatants shown in the marvellous illustrations of Jrg Wilhalms codex may not have come out of their encounters so easily.

Books that feature single combat techniques have a long tradition. Fechtbcher , as they are called (in English: fight books), were produced beginning in the 14th century in the form of manuscripts, the majority of them in Germany. Later ones were printed, but even after the advent of print in the year of 1455, many fight books were entirely hand-crafted. This is the case for the five volumes attributed to Jrg Wilhalm, which stem from the 1520s. At that time, the kind of serious combat they present, the duel in and out of armour, with the long sword and other medieval weapons, was already falling out of fashion as more modern weapons arose, particularly the rapier but also firearms. In this regard, Jrg Wilhalm was one of the final witnesses of an ancient art that would soon be looked at as only a curiosity, as a distant relic from the past. Wilhalm was not only a practitioner but also a preserver of an art that was slowly falling into oblivion.