Titles in the Decadence from Dedalus series include:

Senso (and other stories) - Boito 6.99

The Victim (L'Innocente) - D'Annunzio 7.99

Les Diaboliques - D'Aurevilly 07.99

Angels of Perversity - de Gourmont 6.99

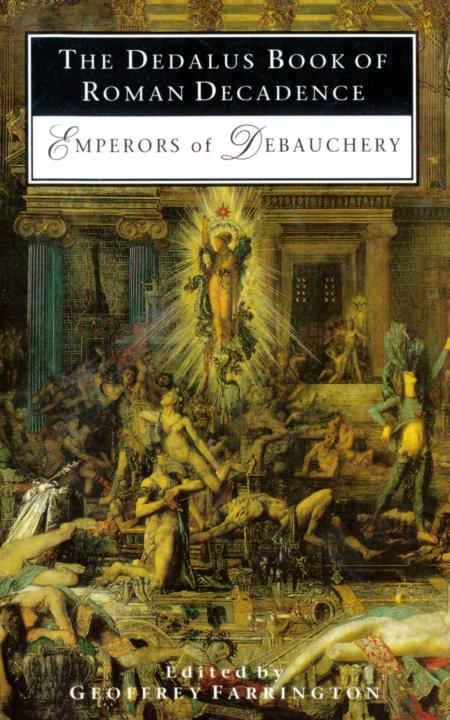

The Dedalus Book of Roman Decadence - Farrington 8.99

The Dedalus Book of German Decadence - Furness 9.99

La-Bas - Huysmans 7.99

The Road to Darkness - Leppin 7.99

Monsieur de Phocas - Lorrain 8.99

The Green Face - Meyrink 7.99

Abbe Jules - Mirbeau 8.99

The Diary of a Chambermaid - Mirbeau 7.99

Le Calvaire - Mirbeau 7.99

Sebastien Roch - Mirbeau 9.99

Torture Garden - Mirbeau 7.99

Monsieur Venus - Rachilde 6.99

The Marquise de Sade - Rachilde 8.99

The Great Shadow - Sa-Carneiro 8.99

Lucio's Confessions - Sa-Carneiro 6.99

Dedalus Book of Decadence - Stableford _f 7.99

The Second Dedalus Book of Decadence - Stableford 8.99

Autumn & Winter Sonatas - Valle-Inclan 7.99

Spring & Summer Sonatas - Valle-Inclan 7.99

Contents

(Unless stated otherwise all the translations are by either Brian or Adrian Murdoch)

THE EDITOR

Geoffrey Farrington was born in London in 1955. After drama school he worked as a scriptwriter and performer in theatre, radio and television, along with helping to run the family business in South London. He is the author of a decadent novel set in the reign of Nero, The Acts of the Apostates (Dedalus 1990), and a vampire novel, The Revenants (Dedalus 1984).

THE TRANSLATORS

Adrian Murdoch was educated in Scotland and at the Queen's College, Oxford. After graduation he taught in Berlin for a year, working as well for the Ministry of Education as a translator and interpreter. He now works as a journalist in London.

Brian Murdoch studied at Exeter University and at Jesus College, Cambridge, and is currently Professor of German at Stirling University. He has published a large number of books and articles on medieval (and modern) Germanic, Celtic (especially Cornish) and comparative literature, as well as translations of medieval Latin and German epics. He is currently editing the Dedalus Book of Medieval Decadence, which will appear in 1995.

INTRODUCTION

Throughout history nothing has been more synonymous with decadence than imperial Rome. There are a good many reasons for this - aside from hackneyed images of gladiatorial combats and orgies - and foremost among them are probably the Roman emperors themselves. Certainly these men held more personal power than any other individuals in history, but the unique tradition and history of Rome meant that their power was very fiercely resented.

Rome grew from a small, monarchic city state, expelling the last of its Etruscan kings, the tyrannical Tarquinius Superbus, in the sixth century BC, and founding a republican system (or more accurately an oligarchical system) whose dubious concept of freedom became ingrained within its citizens as their greatest pride. This pride, and the dedication it engendered, did much to raise Rome to its eventual imperial glory, but the political system which guided Rome to greatness became finally the victim of its own success; citizens voting and senators debating was a method of government wholly inadequate to rule a world empire. And with empire came wealth, and with wealth ever greater corruption. Numerous upheavals among members of the leading Roman families as they vied for position and advantage led ultimately to civil war and the irrevocable collapse of the republican system.

The dictator Julius Caesar - granted special authority at a time of emergency - despite his contrived and ostentatious refusal of the title `king', was assassinated on the Ides of March in 44 Bc by those men faithful to the republican ideal who saw that Caesar aimed at kingship in all but the hated title (Caesar's own title of perpetual dictator would seem similarly odious to modern ears) but who also believed that his assassination would be sufficient to save the republic. This was tantamount to supposing that Caesar, his body lacerated by twenty-three stab wounds, might be revived by artificial respiration.

But the lesson to Caesar's adopted son and heir, his grandnephew Octavian (later the Emperor Augustus) was clear. The Romans - more specifically the Roman nobles - would not yet accept a ruler outright. A less flamboyant figure than Caesar, but no less ambitious (it is historically astonishing that two such different but remarkable men should have risen in succession to combine their abilities in such a monumental undertaking), Augustus set about painstakingly imposing his own solution to the problem. Having delivered Rome finally from the turmoil of civil war, and defeated at the naval battle of Actium his once colleague and later rival, Caesar's lieutenant Mark Antony in his alliance with Queen Cleopatra of Egypt, Augustus declared himself `Imperator' (supreme military commander) from which the title `emperor' was to derive and 'Princeps' (first citizen), who exceeded others not in power but in authority (Augustus' own words). To which any astute senator might have replied: `Yes. And I am the Queen of Parthia's aunt Betty.'

Through a facade of empty republican traditions and titles, Augustus used this `authority' to rule absolutely for forty years, and to pass on his powers to his chosen successor, his stepson Tiberius, when he died.

As time passed the pretence naturally wore thinner as subsequent emperors - particularly Caligula and Nero - became ever less discreet about cloaking the reality of their power. They were, of course, greatly resented by those senators, members of the old nobility whose forbears had survived the ruthless proscriptions upon their number by Augustus after the civil wars, and whose ancestral power and authority the emperors had usurped. They might still achieve the great republican offices of state - become quaestors, aediles, praetors and ultimately consuls - but these titles were finally little more than mere honours. All true promotion and advancement lay in the hands of the emperor. Political impotence bred indignation, and a nostalgia for the republican system, whose instabilities and impracticality these later generations had never experienced. Conspiracies against emperors became commonplace, and so consequently did the executions of those among the nobility whom emperors mistrusted. This frequently was most of them, given the enmity that grew between emperors and senate, and the progressive exclusion of senators from all real areas of power. The purges were particularly fierce within the imperial family itself. Every emperor after Augustus regarded his relatives as his closest potential rivals, and a likely focus for malcontents and conspirators; as indeed they often were. When Nero died in 68 AD the once abundant line of Augustus became extinct.